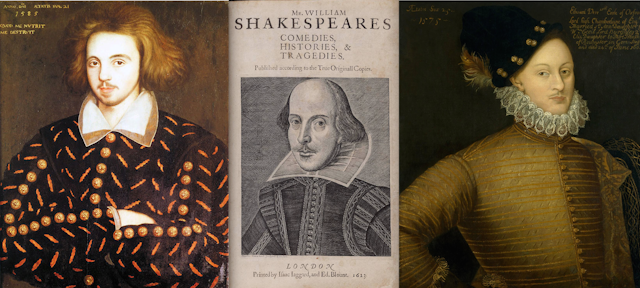

If you have any sort of interest in Shakespeare, you’ll be well aware that there’s been a long-running debate between those who think the man from Stratford upon Avon wrote the works that bear his name and those who don’t. A series of different figures have been proposed, including Christopher Marlowe and the Earl of Oxford, but there’s no consensus by any means. The most popular candidate for the Bard remains the man who died 400 years ago this April.

But my research into Shakespeare’s use of dialect scores a goal for those, like me, who doubt the authorship of the canon. Shakespeare’s use of Warwickshire, Cotswold and Midlands dialect is a key argument used by those who stand by the traditional author. Dialect words from the area around Stratford-upon-Avon are present throughout the plays, according to Shakespeare Beyond Doubt, a book edited by Stanley Wells and Paul Edmonson, respectively Former Chair and Head of Research of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Similar claims were made by historian Michael Wood in his 2004 BBC series In Search of Shakespeare.

But as I have shown, these so-called “Warwickshire dialect” words are nothing of the sort. Thanks to digitised databases, it’s now clear that not a single one of the two dozen words and phrases that have been argued to come from the Cotswolds – from “ballow” and “batlet” to “pash”, “potch” and “unwappered” – are actually local words.

Many of these words were commonly used at the time. Take “mazzard”, a type of cherry, used as slang for the head in both Hamlet and Othello: “I’ll knock you over the mazzard.” A search of Early English Books Online reveals that Shakespeare’s contemporaries Anthony Munday, Thomas Middleton, Nathan Field and Francis Beaumont all used “mazzard” for head. None of them came from Warwickshire.

“Breeze”, another word for a gadfly, is used in Antony and Cleopatra, but the claim that it is Midlands dialect ignores the fact that it was a commonly-used word from Old English, used by Chaucer and by the Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser (among others) in texts Shakespeare is likely to have read.

More widely spoken was “kecksies”, used as a name for hollow-stemmed plants such as cow-parsley. Though the Oxford English Dictionary notes Henry V as the first appearance of the word in print, “kecks” entered the language with the Vikings, and variants on “kecksy” were noted in numerous counties besides Warwickshire, including Yorkshire, Dorset, Essex, Somerset and Cornwall. This is not a word that can be used to prove that an author hailed from the Midlands.

Golden lads

Other words and phrases touted as dialect arose out of myths and mistakes. The 2011 Royal Shakespeare Company edition of Cymbeline tells us that “golden lads” and “chimney-sweepers” are Warwickshire dialect for the dandelion flower in its two stages, and their becoming “dust” is a reference to what happens when the seed-head is blown. But a recent paper revealed that this was a “20th-century myth, perhaps even a hoax”. Shakespeare was being literal, not poetic. He was referring to the high-born and the low-born meeting the same end: death. The “dandelion” idea is a fiction which was popularised in two novels of the 1950s and subsequently transformed into an invented anecdote.

The early play Titus Andronicus tells us that “honey-stalks” are poisonous to sheep, and cause them to rot. Not knowing what Shakespeare meant by “honey-stalks”, his 18th-century editor, Samuel Johnson, decided he must mean clover blossom. Despite the objection of a more agriculturally savvy peer, who observed that when it came to sheep, clover was “the wholesomest food you can give them”, Johnson’s authoritative critical standing led to “honey-stalks” entering the English Dialect Dictionary as Warwickshire dialect. But easy access to 16th-century husbandry manuals brought about by digitisation has clarified the author’s reference point: “Honey-stalks” is his poetic conflation for “stalks covered with honey-dew”. It was only listed in the English Dialect Dictionary as Warwickshire dialect because Shakespeare had used it, and Shakespeare was thought to be from Warwickshire.

This kind of circular reasoning is the cause of many of the mistaken claims for Shakespeare’s use of dialect. The English Dialect Dictionary, compiled 300 years after Shakespeare’s time, is one of several sources scholars have used to support their arguments. But the earliest dialect glossary was not published until 1790, and most were in the second half of the 19th century, when Bardolatry was in full-swing. As a result, Shakespeare words that seemed unusual or unique were sometimes listed as Warwickshire or Cotswold dialect, often with a quote from an appropriate play as evidence. We cannot therefore rely on these secondary sources as evidence that a word was Midlands dialect. With the resources of our digital age, it is easy to prove that these early compilers were mistaken.

To the gallows

Take “gallow” for example, used to mean “frighten” in King Lear. Huntley’s Glossary of the Cotswold Dialect (1868) includes this word, quoting Shakespeare as his source. We have no evidence that Shakespeare picked this up in Warwickshire. But “gallow” was used to mean “terrify” in a 1568 treatise by John Fenn, an Oxford fellow born in Somerset and educated in Winchester. Either Shakespeare read Fenn’s text, or he arrived independently at this instance of poetic metonymy. Either way “gallow” is not Cotswold dialect.

Defending the traditional authorship of Shakespeare’s works is entirely understandable, but this particular strand of defence – that Shakespeare used Warwickshire and Cotswold dialect – does not stand up to scrutiny.

That the author cannot be pinned to a particular location by his diction doesn’t mean that “Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare”, but it does mean that defences of the traditional author will need to focus on other arguments. The bonus is that as a result of challenging this traditional authorship defence, we gain a better understanding of what Shakespeare intended by “honey-stalks”, and what he meant when he wrote that:

Golden lads and girls all must

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

Shakespeare is an author so encased in mythography and “biografiction” that it is hard to get a sense of the real human being. Stripping away biographically grounded assumptions might feel threatening to some, but it is a route to greater clarity about his works; which are, after all, the only reason we are interested in him in the first place.