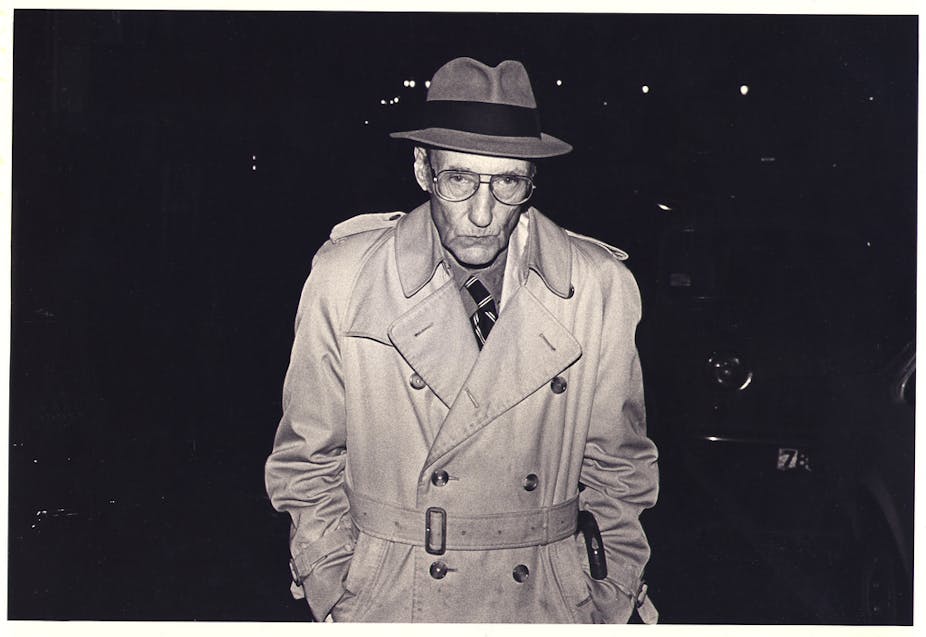

When William S Burroughs returned to New York City in 1974, after two decades of peripatetic rambling, dubious pleasure and restless escape, the rising rock poet Patti Smith expressed her deep pleasure from a downtown Manhattan stage:

Do you know who just moved back to New York? William Burroughs just moved back to New York! Isn’t that great?

It might seem odd that a young female performance artist, entangling acerbic verse and the crackle of the electric guitar, about to light punk’s blue touch paper, was delighted that this besuited and seriously senior doyen of the literary scene was back in her home town after so many years away.

After all, Burroughs, whose centenary was celebrated on February 5th, had scant interest in popular music. In fact, the sonic arts broadly left him cold. He liked words and films and loved to chop them into pieces and reassemble them in disturbing, non-consecutive patterns, a skill learnt under Brion Gysin at the Beat Hotel in Paris.

But what this writer did possess was a deep understanding of the decaying present and an almost uncanny vision of a dystopian future. His cities, like the imaginary Interzone of Naked Lunch, were symbols of the crumbling edifice of Western civilisation.

The punks – taking their places in the dankest quarters of the then squalid East Village and the fringes of the Chelsea Hotel – drank up his Boschian word paintings like the elixir of truth. New York was going out of business, the pillars of the capitalist temple were tumbling, and Burroughs’ twisted visions – perverse and pessimistic, transgressive and terrifying – appeared the perfect prose accompaniment to the post-Velvets soundscapes the New York Dolls, Patti Smith, Television and The Ramones were scoring.

This year, Lawrence, Kansas, the Midwest town where Burroughs ended his mortal days in 1997, will welcome fans, followers, friends and scholars to a series of events that will endeavour to make sense of a novelist who attracted all shades of opinion in life. Brilliant and innovative, radical artist and postmodern totem as penman, he was also considered a drug-addled pederast, not to mention a common street thief and even the killer of his common law wife.

He was all those things, as well as a Harvard graduate who studied psychoanalysis in Vienna before the war and brought back a Jewish wife, even though it was men, and later Arab boys, who most took Burroughs’ fancy. He was also heir to part of the Burroughs Adding Machine fortune and used his monthly allowance over a whole epoch to fund his louche and dissolute lifestyle, indulging in every narcotic available and reading Spengler, Céline and other prophets of cultural doom to while away the time.

But back to the opening question: how did Burroughs become a guru to that revolutionary rock community of the Big Apple? How would he attract the sobriquet “the Godfather of Punk”?

Burroughs belonged to the mid-1940s circle that was dubbed the Beat Generation, along with younger players like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso. They were a group of poets and novelists whose messages would, in time, rattle the cages of a complacent establishment.

Within ten years, all would become the controversial, yet acclaimed, commentators on a US torn between the material riches of economic boom and a crisis of existential paranoia. Each month seemed to promise the chance of nuclear annihilation at the hands of the Soviet enemy. In Howl, Ginsberg raised questions about race, sexuality and war; in On the Road, Kerouac paraded a vision of hedonistic, hitchhiking escape. Burroughs wrote the noir pulp Junkie and then produced his mind-searing sci-fi satires in Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine.

By the mid-1960s a new generation of creative giants had been washed on the transatlantic shores. These were musicians rather than authors, in the shape of Dylan and the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Doors. Rock abandoned teen romance and took on politics and poetry, drugs and self-revelation, much as that earlier wave of writers had done.

Yet there were paradoxes here, too. While Ginsberg stepped easily into the shoes of the rejuvenated scene, befriending Dylan and McCartney and leading anti-Vietnam demos from the front, Kerouac despised the counterculture and LSD, dubbing them Russian plots, and arch-cynic Burroughs, by now a renegade wanderer from Tangiers to France then London, despised peace and love and spirituality, the beacons of hippydom.

However, once the hippy dream faded – the war went on and Nixon survived – the darker shadows of the inner city begat the fast and furious assault of punk and the bleaker visions Burroughs had woven seemed to ominously and wonderfully chime with the new reality – bankruptcy, the lure of the gutter and the needle.

Burroughs carried the fight forward in the wake of the 60s, associating with the New York Dolls and Patti Smith, Lou Reed and David Bowie, attending the raw romps at CBGBs, and proving that rock and the written word did not have to lead exclusive and divided lives.

Burroughs was dubbed, by no less a figure than Norman Mailer, “the only American novelist living today who may conceivably be possessed by genius”. He was an avant garde mover and shaker since the second world war. He was a notorious breaker of taboos – a homosexual who smashed most social and literary rules and relied on the distortion of the senses to produce his stream of consciousness tales. But most of all, perhaps, it was the punk underworld of 1970s New York that most heralded his Big Apple comeback as an absent father figure and a maverick inspiration.