At the end of January, the Cleveland Indians announced that their mascot, Chief Wahoo, will no longer appear on players’ jerseys beginning with the 2019 Major League Baseball season.

Since the 1970s, activists have opposed the mascot, arguing it is offensive, discriminatory and harmful to Native Americans. Pending litigation against MLB and the Cleveland Indians over the discriminatory nature of the logo likely created additional pressure.

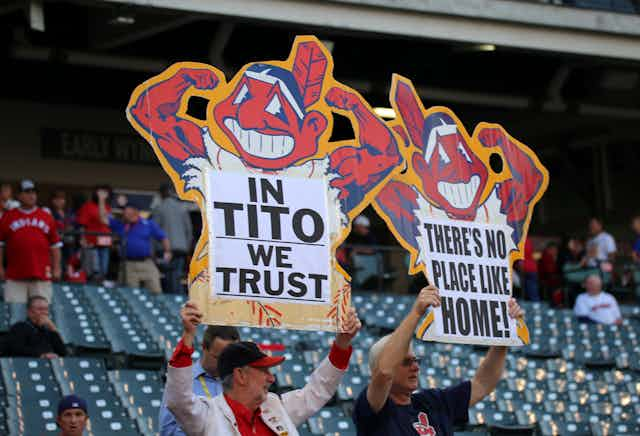

Many – including some Cleveland fans – heralded the decision as a long overdue. But other Cleveland fans were upset with the decision. They don’t see Wahoo as a racist symbol; instead, they associate it with their communities and childhoods.

For the past 13 years, I’ve been studying Native American cultural and legal disputes. But in recent years, I’ve been particularly interested in the rhetoric used by defenders of these Native American sports mascots.

While many scholars are quick to note a Native American mascot’s racist and colonial underpinnings, not enough attention is given to the fans and defenders’ attachment to these symbols. To them, it has nothing to do with the appropriation of Native American culture.

Instead, it’s about community, identity and nostalgia. And it’s for these reasons that Chief Wahoo will continue to be embraced by the team’s fans for years to come.

The rebirth of a city and its baseball team

From 1960 to the late 1980s, few fans paid attention to the Cleveland and its mascot.

They fielded only a handful of winning teams, and the team had no playoff appearances between 1954 and 1995. Off the field, financial problems and frequent ownership changes only compounded the team’s problems.

When he purchased the team in 1986, real estate developer Richard Jacobs wanted to revitalize the team by “embracing Indians history” and constructing a new stadium. Both involved the prominent use of Chief Wahoo. For example, after Jacobs purchased the team, Wahoo replaced the block letter “C” on the players’ caps.

In the 1990s, downtown Cleveland experienced an economic revitalization, while the Indians put together a string of playoff runs. As the team and city’s fates improved, the identity of the city and team became intertwined.

Professor of sports management Ellen Staurowsky has specifically written about the close relationship between the Cleveland Indians and the city’s identity – one that’s “overpoweringly revealed on opening day in Cleveland, when people throughout the city literally wear their loyalties on their sleeves.”

Strident defenders of the logo echo this sentiment. For example, a fan named Pedro Rodriquez told Cleveland Scene in 2014 that the mascot is about “Cleveland pride” and nothing else.

It’s about more than sports

The University of Queensland’s John Nauright has written extensively about how sports have long operated as “one of the most significant shapers of collective or group identity in the contemporary world.”

While the link between a team and community’s identity might explain some of the mascot’s defense, there’s also an emotional intensity attached to Chief Wahoo.

During the 2016 playoffs, a middle-aged woman, on the verge of tears, told protesters that “Chief Wahoo is my beloved man.” On opening day in 2017, anti-Wahoo demonstrators were greeted with profanity and obscene gestures.

What explains this fervent defense of the mascot – and the rage felt toward those opposed to the logo? After all, isn’t it just sports?

Research demonstrates that sports – particularly professional baseball – are connected to nostalgic feelings for the past. Pioneering sports marketer (and former Cleveland Indians owner) Bill Veeck wrote that baseball should be marketed in a way that creates vivid and lasting memories, evoking feelings that make fans want to return each season. For kids going to their first baseball game, there’s probably no better way to brand the team than with a grinning cartoon character that mimics the ones they see on TV.

Sure enough, when many fans talk about their feelings toward Chief Wahoo, they’ll associate the team and its mascot with happy childhood memories.

Even a critic of Chief Wahoo, Nick Galaida, admits as much: “Chief Wahoo is more than a team logo,” he wrote in 2017. “[It] represents countless summer hours spent with my friends and family eating hot dogs and cheering on our team.”

These feelings probably allow fans to look past any sort of latent racism; to them, the image is connected to an innocent place – childhood – and is immune from bad intentions.

Changing the parameters of the debate

In the national debate about Native American mascots, it’s important to understand how fans feel about their mascots.

For many, elimination of the mascot is an attack on their personal identities, worldviews and histories. As cultural anthropologist C. Richard King notes, “For many fans change brings with it certain violence. And while largely effective, change would strike at the heart of who they are and what makes the world good.”

So the problem isn’t just the presence of a symbol that many find offensive. It’s the emotional connection that fans feel toward the symbol. In her book “The Promise of Happiness,” scholar Sara Ahmed argues that happiness isn’t located in the image of Wahoo. Instead, the way Wahoo is talked about – and debated, and threatened – makes fans think that a symbol like Chief Wahoo is associated with better times.

So how should all of this inform the debate over team mascots?

Rather than simply focusing on removing the image and calling it “racist,” there could ideally be more discussion about some of the problems Native American mascots pose. (For example, recent research has detailed how they reinforce stereotypes.) At the same time, those who want to get rid of Wahoo should also acknowledge the deep emotions fans feel toward the mascot.

For now, it doesn’t look as if the Indians’ decision to remove the mascot from its uniforms will succeed in relegating it to the annals of history. The agreement between the team and the league leave the team’s name unchanged; it also permits the sale of Wahoo-themed merchandise at games and on the team’s website. Fans won’t be prohibited from wearing the logo at games.

Chief Wahoo will remain central to the identity of the team and its devoted fans.