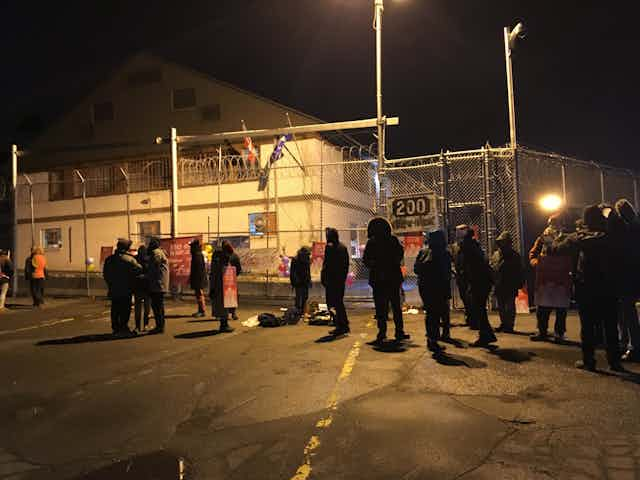

On April 13, Montreal resident Lucy Francineth Granados was deported to Guatemala. Despite mobilization by groups like Solidarity Across Borders and No One is Illegal, Granados was not allowed to stay in Canada.

The way the media portrays racialized immigrants plays an important role in these situations and in general exerts much power over how we imagine our nation. This is particularly true when an audience has little or no knowledge of the community being represented.

Journalists and media producers tend to use short-hand devices that portray good versus bad citizens and racial minorities as “others” who can never fit into Canada or whose differences can only be tolerated if they become like “us.” For example, crime TV shows are designed to intimidate populations by scaring them with demonstrations of the negative outcomes of breaking laws.

Read more: American-style deportation is happening in Canada

In this way, the mass media use different people to communicate symbolic messages. Sometimes, the lack of cohesion in these messages demonstrates conflicting viewpoints, illustrating differences of opinions and mandates within government or news agencies, and thus maintaining a semblance of objectivity and balance.

At other times, though, such messages, especially when they revolve around issues like illegal immigration, tend to be quite uniform.

For example, in cases involving representations of racialized minorities, research shows how most mainstream media tend to either portray them as exceptional cases of success, or more frequently, they are portrayed as criminals or people who don’t fit in.

Lucy Granados was used as an example

The government said Granados had committed a crime by remaining in the country for nine years as an undocumented worker after her initial application for refugee status was denied. Granados came forward and applied in the hope her status would be legalized.

This, in itself, was a risky move and it alerted the authorities right away that she had been residing in the country illegally.

The government denied hearing Granados’s case to stay on humanitarian grounds. I believe Granados becomes the example of what the state will not tolerate. Her deportation sends a message to other undocumented workers that if they come forward in order to seek legal status they too will be at a heightened risk of deportation.

The deportation of Lucy Granados and other undocumented workers and the way these stories are talked about needs to be contextualized within a wider set of issues. Primarily among these is the continued and growing anti-immigration sentiment that remains a consistent thread in the nation’s fabric. It is partly fuelled by the amplifying power of the mainstream media and its reliance on bureaucratic sources of power and authority (government, police, courts).

A wave of anti-immigration

With recent media portrayals of Haitians and others crossing the borders, there is a heightened panic that the immigration system has broken down and that the country will be overwhelmed by its benevolence.

At the same time, the story is that Ottawa is doing what it can to stem the tide and to defuse the impact of misinformation about the immigration system.

This backdrop then informs the Granados case, but fails to rectify the situation. Rather, it simply underscores the reality that we have become like the United States in terms of expelling and deporting those we don’t consider as “fitting into” our nation.

The tide of anti-immigration sentiments is apparent in other instances.

For example, Québec Mosque shooter Alexandre Bissonnette shot and killed six Muslims and injured 19 others at the Québec Grand Mosque because he was afraid of an imminent terrorist attack and because as he said in court, “the Canadian government was, you know, going to take in more refugees, you know, those who couldn’t go to the United States would end up here.”

Bissonnette was not simply reacting in a vacuum. He had heard news reports about Muslim terrorists, followed U.S. President Donald Trump’s incessant tweets and watched YouTube for information on guns. He was convinced his family was in danger of a terrorist attack. So, he chose to act first by annihilating what he thought was the threat.

The perceived threat was sparked by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement welcoming refugees following Trump’s travel ban prohibiting visitors and immigrants from seven Muslim majority countries. Framed in this way, his actions are rendered legible — though insane.

The refugees and potential terrorists (read Muslims) are then to be blamed for Bissonnette’s mental decline and his murderous actions. To be sure, Canada has accepted a high number of refugees but are these refugees to be blamed for seeking entry and for striving for a better life?

Exceptional immigrants versus criminal ones

The media’s framing of refugees and immigrants as threats has been widely documented in existing studies, both here and in other Western nations. These, overwhelmingly, negative depictions fuel moral panics when refugees and immigrants are portrayed as flooding into the nation. The language of the stories suggest an “avalanche,” or “invasion” that threatens the nation. The pictures accompanying such stories tend to present the refugees in huddled masses, or as masses on the move.

The stories rarely touch on the contributions of these immigrants and refugees. Many of them are sponsored by families, organizations and concerned others. They pay taxes, buy goods and do the jobs that no one else wants to do. Though trained as doctors, lawyers and engineers, many end up driving taxis, opening small businesses like restaurants and feeding the economy in other ways. Their contributions feed the nation, supplement our reserves, supplying the funds that will sustain our future be it through social programs or the consumer economy.

Just as race exceptionalism in media representations can work to make icons of particular success cases, so can stereotyping make them appear as if they are all the same. The illegal refugee comes to stand in for all refugees, as does the illegal immigrant.

In a recent interview I participated in on CJAD Radio (popular among Anglophones in Montréal), Neil Drabkin, an immigration lawyer responded to my analysis about the diverging reality between the rhetoric of Canada as a benevolent nation and the reality of the brutality of deportation by beginning his interview segment with the following statement: “Let me put down my violin.”

His statement was designed to convey to listeners a dismissal and trivialization of my argument and position me as one of a “bleeding heart liberal” telling a sob story.

I wonder how all those Canadians who have privately sponsored Syrian and other refugees, or families that have sought to reunite with their loved ones would feel about this. And what about the painstaking work that non-profit organizations do about safeguarding the rights of those who have no rights in this country?

Permanent resident status should be based on more than formal rules and regulations. It should take into consideration the work that people have done for the good of society, not just in terms of economic investment, but in terms of working towards a more equitable and just social order. To wit, at the end of the day, the nation state is a constructed entity - real sovereignty belongs to Indigenous nations. Yet, as history reveals, the dispossession of Indigenous sovereignty is the state’s way of ensuring a particular kind of nation.

Had the existing structures taken this into account, Lucy Granados who worked for nine years in Montréal to support women workers, might have had her deportation order stayed.