Human beings have a surprisingly long relationship with the concept of swimwear. After all, the first heated swimming pool is believed to have been built by Gaius Maecenas of Rome in the 1st century BC.

Before the early 1800s, it was relatively common to swim either nude or simply in your underwear. When communal swimming baths became more popular and prevalent in the mid-19th century, decorum demanded men and women cover their modesty with garments made specially for the purpose. Women covered up with cotton or wool bathing dresses, drawers, and sometimes even stockings.

While seeming ungainly today, these impractical garments must have been liberating for women used to corsets and long, hampering skirts worn over multiple petticoats. By their very nature these “swimming suits” also threatened entrenched ideas around feminine activity (or lack thereof), perhaps suggesting women who swam energetically could no longer be considered “the weaker sex”.

Nonetheless, modesty presided above all else during this period, and it wasn’t until women began to swim competitively that change began.

A scandalous arrest

Water, particularly the beach, has been described by fashion scholars Harold Koda and Richard Martin as the “great proscenium of twentieth-century dress” – a statement that encourages us to rethink the importance of swimwear in our everyday dress and lifestyles.

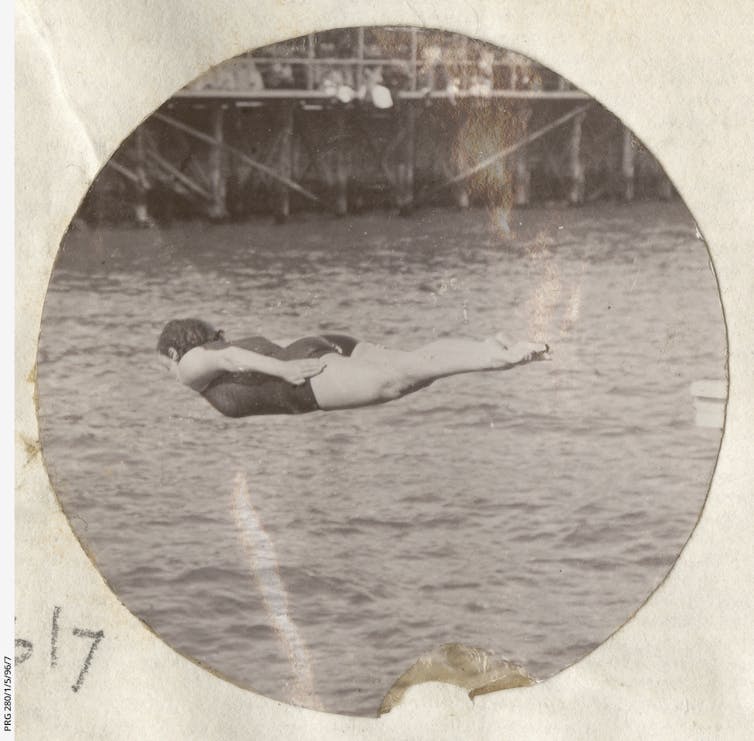

In 1907, Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman was arrested on Revere Beach, Massachusetts, for wearing a one-piece bathing suit in public. This garment was a sporting necessity, and fellow athletes successfully championed a skirtless, sleeveless one-piece for the 1912 Olympics.

Kellerman’s incredible figure was admired as much as her actions were berated, and she was known to strip down to her bathing costume in all-female public lectures, proving a healthy lifestyle (rather than a corset) was to thank for her silhouette.

“If more girls would swim and dance and care for athletics”, she commented in 1910, “instead of rushing into matrimony as the only joy in the world, there’d be fewer divorces”.

The new one-piece contributed hugely to what has been described as the “erotic theatre” of the pool edge: swimwear is an item of both form and function, and so the pool or sea is an acceptable space to bare all.

Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie

The introduction of elastic yarn in the 1930s created a fabric that clung to the body and enabled risqué designs.

The influence of the Hollywood starlet, lying immaculate (and dry) by a sparkling pool sowed the seed swimwear need have nothing to do with exercise. It could instead suggest leisure and luxury: the embodiment of a society now used to annual holidays.

The 1940s introduced what we now recognise as the bikini, and the 50s saw iconic portrayals of swimsuits worn by the likes of Esther Williams and Marilyn Monroe.

The swinging 60s opened with Brian Hyland’s Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie, Yellow Polka Dot Bikini, and further promotion through the Bond franchise firmly cemented the bikini’s erotic prowess.

Soon, swimwear’s eroticism was being used by some to promote ideals of gender equality and acceptance.

In 1964, Austrian-American designer Rudi Gernreich introduced his notorious “Monokini”, a bathing suit featuring two skinny straps just grazing the breasts.

Gernreich hoped the suit would challenge existing prudishness and shame around the nude female body. His plan backfired. From its birth, the press described the monokini as controversial – and, although it sold well, it never became conventional swimwear.

The 1970s and 80s welcomed fashionable suits and bikinis with less internal structuring, fitting the silhouette of the decade. Fashionable first and practical second, they could still withstand a certain amount of sun, sand and chlorine.

A protest symbol

Swimming, fashion, and baring all are not mutually exclusive.

“Rashies” or “rash guards” (so-called because they protect the wearer from rashes and sunburn), are long-sleeved waterproof shirts that first originated as surfwear. In countries like Australia with prominent beach culture and harsh weather the garment has grown in popularity.

In 2004, Australian designer Aheda Zanetti, inspired by the increasing presence of Muslim women in Australian sports (especially swimming), created the “burkini”. Acting as a kind of lightweight wetsuit, the garment covers the entire body and comes in a variety of styles and colours.

The style came under intense scrutiny in 2016 when several French municipalities banned the burkini in line with the country’s secular laws (it had banned the wearing of a burqa and niqab three years earlier).

It doesn’t seem to matter whether women’s swimsuits bare-all or cover-all: those wearing them will still be judged. But much as the shift from bulky dresses to lean one-pieces opened up new opportunities for women in the water, this latest suit also makes the beach lifestyle more accessible, with wearers remaining both cool and UV-protected.

With our “house on fire”, as Thunberg eloquently put it, we may be seeing more swimsuit innovation heading our way as a matter of necessity.