As we undertake our annual remembrance of Australians at war, some attention should be paid to those personnel who were taken captive by the enemy and then faced long years in brutal conditions. Enduring starvation, beatings, disease, death marches and forced labour in extreme climatic conditions, many of them died from casual neglect, deliberate abuse and untreated medical conditions.

And I’m not talking about prisoners of the Japanese in World War Two, but Australians taken captive by Ottoman forces during The Great War.

Just over two hundred Australians fell into enemy hands during our involvement in the Allied fight against the Ottoman Empire. Amongst those troops taken at Gallipoli and in Palestine, there were also some pioneering Australian submariners and a group of our very first aviation personnel. These last went into the bag during the relatively obscure Mesopotamian campaign; a four year effort to dislodge the Ottomans from what is now Iraq.

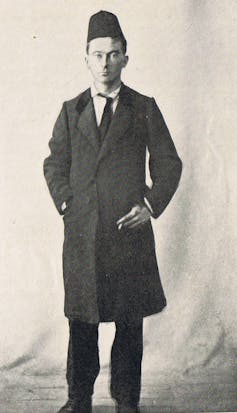

One of these airmen, Thomas White, was captured in a hare-brained plan to disrupt enemy signals by blowing up telegraph poles. No smart bombs or Tomahawk missiles being available, in 1915 this meant landing your aircraft behind enemy lines and sending your observer out to place dynamite on the poles whilst you hauled the plane round manually to face back into the wind. Predictably it all went horribly wrong. White’s ensuing memoirs of his years in captivity describe the privations Allied troops endured whilst also bearing witness to the depredations of the Armenian genocide that was going on around them.

Guests of the Sultan

In some contrast to those held prisoner by the Japanese 30 years later, the poor treatment given to the Allied prisoners of the Ottomans seems to have been the product of systemic neglect rather than wanton cruelty. A corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy exacerbated by the crumbling fortunes of an empire fighting for its life meant that the prisoners held out in the provinces had little access to nutrition and medicine. Not only because it was withheld, but because there wasn’t much to access anyway.

White describes how he and his fellow officers had to buy their supplies from local markets. Not being allowed to go and do it for themselves, they had to entrust this transaction to their guards. Naturally the commission taken and the mark-up imposed by the vendor meant that they didn’t get much for their money. But they were still better off than many of their fellows.

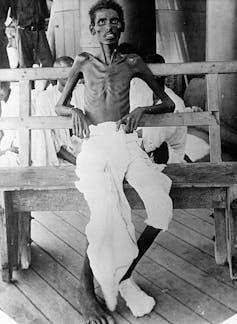

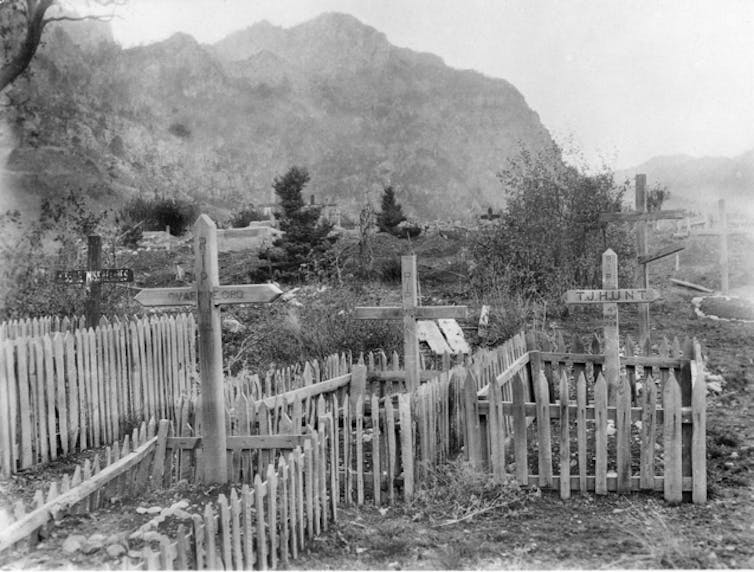

In late 1915, as British and Australian troops were stealthily evacuating the Gallipoli peninsula, others were being surrounded in Kut, a town on the Tigris downstream from Baghdad. Around 13,000 Allied troops eventually surrendered after nearly five months of siege, the majority of them British and many of these from Indian formations. These POWs were then marched over 1,000 km across the desert to Aleppo, with about half dying along the way. The dead included seven of the nine Australian aircraft mechanics who surrendered. The survivors were mainly put to work chiselling railway cuttings out of the rock of the Taurus Mountains.

The Indian POWs were subject to a higher level of abuse and neglect from the Ottomans than the white prisoners. Often they were not even housed under cover, being forced to sleep outside without any blankets or shelter. In the winter they died by the score every night. Around 70% of the thousands captured never saw home again. White’s account of such pitiable conditions and the sight of skeletal men carrying their dead comrades for burial every day make for poignant reading and certainly evoke comparisons with the POW experience under the Japanese. Of the two hundred Australians taken by the Ottomans, about a quarter died during their captivity.

A question of image

White’s own escape was worthy of a screenplay: jumping from a train, being chased through the streets of Constantinople and then smuggling himself aboard a freighter to Odessa, then in the throes of Bolshevik revolution . He made it to London, married the daughter of the former Australian PM Alfred Deakin, and then came home to a long, distinguished career in federal politics, aviation and finally, as High Commissioner to Great Britain. (At the Point Cook RAAF base you can still see a heritage listed dent in one of the hangars from White pranging his Bristol Boxkite during training in 1914.)

However, the Australian airman was forever irritated that a ‘tough but fair’ image of the Turks came to prevail in the years following the war. Stemming largely from the Gallipoli narrative, White also felt that this positive impression had been supported by complimentary letters home from Australian prisoners, especially those held at the ‘parolee camp’ at Gedos. Here, captive officers who contracted not to attempt escape were left unguarded and kept in much greater comfort than those in the general military prisons. White’s scorn for those who “took the path of least resistance” was great, since he felt they were co-operating with the enemy and this proportionately increased the suffering inflicted on those men, such as White himself, who refused to make such a bargain.

Whether White was right or wrong in this hypothesis, it seems fair to say that today the Japanese hold a more negative (and less reconciled) image regarding their treatment of Australian prisoners of war than the Turks are afforded.

Beyond the beaches

In its popular format Anzac Day is often focussed on the Gallipoli landings, with less emphasis consequently being placed on other events and campaigns of WW1. Arguably there is even less consideration given to subsequent wars and operations. Surrender and captivity also fall outside the ‘glorious’ narratives of war, but the hardships faced by Australian POWs are something we should reflect upon if we want to broaden the commemoration beyond the beaches and gullies of Gallipoli.

And in the story of White and his peers, we don’t even have to move that far in time and space from the famed peninsula to do it.

(Those wanting to learn more of White’s story should try and get hold of his book Guests of the Unspeakable_. It is long out of print, but some of the bigger public and university libraries may hold copies.)_