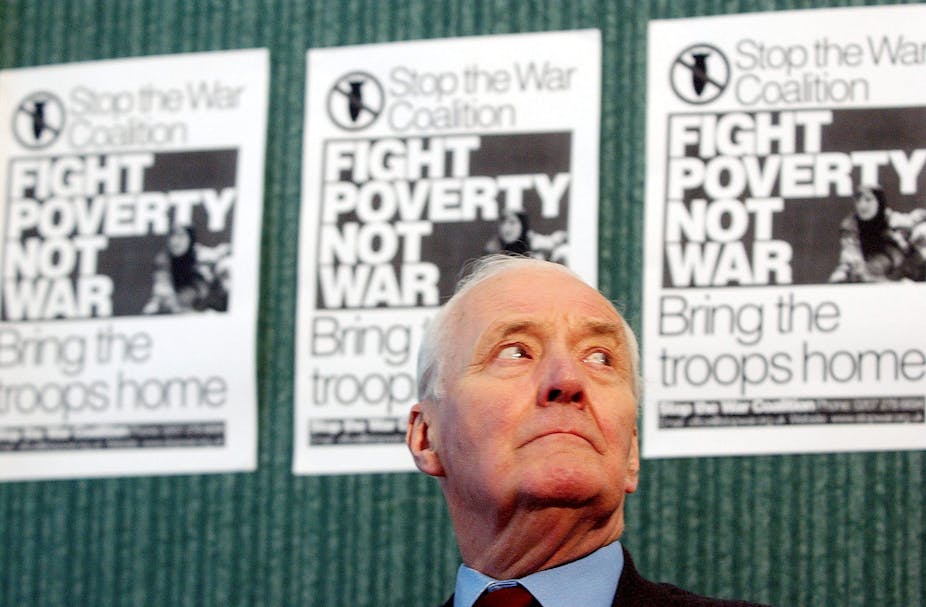

Most of the reactions to the death of Tony Benn have focused on the man who turned left in the 1970s, embraced union militancy and became “the most dangerous man in Britain”. That was, however, Benn Mark II, arguably the less interesting version, and certainly the one less relevant to our own times, one in which the parties are desperately seeking to regain a connection with the people.

A while back I wrote a book about how Labour responded to the many cultural changes generated in the 1960s. In that decade Benn emerged as one of the party’s few leading figures who tried to seriously think though how the party might engage with at least some of them.

Benn Mark I was a fairly conventional politician. In the 1950s he was something of a revisionist and in the 1960s an enthusiastic if idiosyncratic member of Harold Wilson’s inner circle. Benn had also been a BBC producer and had great faith in the political significance of the medium, helping mastermind Labour’s innovative 1959 election broadcasts, which many in the party nonetheless thought too clever by half.

Despite Benn’s efforts, Labour lost the 1959 election: in fact the party in the 1950s was a shell of an organisation. Official party rhetoric referred to the working class but in reality it increasingly only represented the people who ran it.

Benn’s own constituency of Bristol South East was managed by a left-wing gerontocracy of about 15 activists: he considered it “effectively dead”. It was by no means untypical of big city Labour parties of the time.

When Benn contested his elevation to the House of Lords in the early 1960s, he benefitted from a non-partisan local campaign, which reached members of the middle class hitherto reluctant to identify with Labour. The first concrete expression of this progressive non-Labour movement was the New Bristol Group, a body designed to debate issues of importance in the city.

Benn figured there was some way Labour could more permanently tap into those who remained unwilling to join what was often an unwelcoming party. His idea was “Citizens for Labour”, which he envisioned as comprising associate party members who could contribute to but remain outside its official bounds. Benn however hoped it would ultimately become the basis for “a more or less new party”.

Such a new body had to be approved by the national Labour party, specifically the Organisation Sub-Committee of the National Executive Committee (NEC). After what Benn called an “appalling row” it was rejected, with the bovine Ray Gunter warning it had “subversive” potential. Even so, Benn was allowed to launch his initiative on an experimental basis in Bristol South East.

Unfortunately the very activists Benn wanted the new group to ultimately replace were given responsibility to manage it. They ensured Citizens for Labour went nowhere: it was, they believed “out-of-line with general thinking”. In the same spirit they had opposed municipal libraries stocking pamphlets produced by the New Bristol Group.

Benn was not quite alone in seeking new ways for the party to engage with society. When the NEC debated reviving the party’s moribund youth wing it considered sponsoring a movement with no direct ties to the party but with a commitment to “progressive” ideals so it might appeal to more young people. If Benn’s initiative was to some extent inspired by what US Democrats were doing, this proposal was suggested by the experience of European social democrats. But as with Citizens for Labour the party was too timid to embrace such an initiative: the relaunched Young Socialists attracted only Trotskyist entryists and others who were equally if differently weird.

The 1960s was a modernising moment for the party, one it did not seize. Instead Wilson used the rhetoric of “white heat” as a substitute for action. The failure of his government led the party to fall back on a faith in a proletarian militancy that was more myth than reality.

Benn, rightly disillusioned with Wilson was one of those who believed the unions represented the working class and so hitched his wagon to them. To some extent the unions were a short cut to the things he was trying to do in the early 1960s. In the context of the 1970s this was perhaps an understandable mistake to make. But instead of looking outwards to society as did Benn Mark I in the 1960s, Benn Mark II looked inwards to a decaying labour movement: we can now see how wrong he was.