Marvel’s new blockbuster, “Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2,” carries audiences through a narrative carefully curated by the film’s creators. That’s also what Telltale’s Guardians-themed game did when it was released in April. Early reviews suggest the game is just another form of guided progress through a predetermined story, not a player-driven experience in the world of the movie and its characters. Some game critics lament this, and suggest game designers let traditional media tell the linear stories.

What is out there for the player who wants to explore on his or her own in rich universes like the ones created by Marvel? Not much. Not yet. But the future of media is coming.

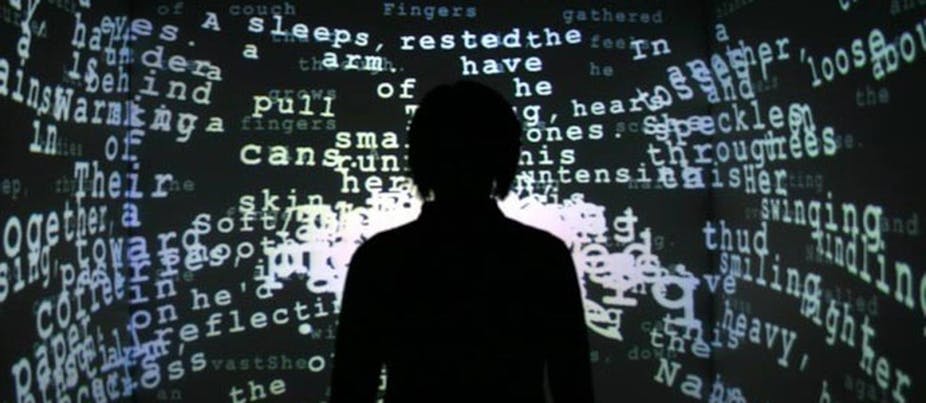

As longtime experimenters and scholars in interactive narrative who are now building a new academic discipline we call “computational media,” we are working to create new forms of interactive storytelling, strongly shaped by the choices of the audience. People want to explore, through play, themes like those in Marvel’s stories, about creating family, valuing diversity and living responsibly.

These experiences will need compelling computer-generated characters, not the husks that now speak to us from smartphones and home assistants. And they’ll need virtual environments that are more than just simulated space – environments that feel alive, responsive and emotionally meaningful.

This next generation of media – which will be a foundation for art, learning, self-expression and even health maintenance – requires a deeply interdisciplinary approach. Instead of engineer-built tools wielded by artists, we must merge art and science, storytelling and software, to create groundbreaking, technology-enabled experiences deeply connected to human culture.

In search of interactivity

One of the first interactive character experiences involved “Eliza,” a language and software system developed in the 1960s. It seemed like a very complex entity that could engage compellingly with a user. But the more people interacted with it, the more they noticed formulaic responses that signaled it was a relatively simple computer program.

In contrast, programs like “Tale-Spin” have elaborate technical processes behind the scenes that audiences never see. The audience sees only the effects, like selfish characters telling lies. The result is the opposite of the “Eliza” effect: Rather than simple processes that the audience initially assumes are complex, we get complex processes that the audience experiences as simple.

An exemplary alternative to both types of hidden processes is “SimCity,” the seminal game by Will Wright. It contains a complex but ultimately transparent model of how cities work, including housing locations influencing transportation needs and industrial activity creating pollution that bothers nearby residents. It is designed to lead users, through play, to an understanding of this underlying model as they build their own cities and watch how they grow. This type of exploration and response is the best way to support long-term player engagement.

Connecting technology with meaning

No one discipline has all the answers for building meaningfully interactive experiences about topics more subtle than city planning – such as what we believe, whom we love and how we live in the world. Engineering can’t teach us how to come up with a meaningful story, nor understand if it connects with audiences. But the arts don’t have methods for developing the new technologies needed to create a rich experience.

Today’s most prominent examples of interactive storytelling tend to lean toward one approach or the other. Despite being visually compelling, with powerful soundtracks, neither indie titles like “Firewatch” nor blockbusters such as “Mass Effect: Andromeda” have many significant ways for a player to actually influence their worlds.

Both independently and together, we’ve been developing deeper interactive storytelling experiences for nearly two decades. “Terminal Time,” an interactive documentary generator first shown in 1999, asks the audience several questions about their views of historical issues. Based on the responses (measured as the volume of clapping for each choice), it custom-creates a story of the last millennium that matches, and increasingly exaggerates, those particular ideas.

For example, to an audience who supported anti-religious rationalism, it might begin presenting distant events that match their biases – such as the Catholic Church’s 17th-century execution of philosopher Giordano Bruno. But later it might show more recent, less comfortable events – like the Chinese communist (rationalist) invasion and occupation of (religious) Tibet in the 1950s.

The results are thought-provoking, because the team creating it – including one of us (Michael), documentarian Steffi Domike and media artist Paul Vanouse – combined deep technical knowledge with clear artistic goals and an understanding of the ways events are selected, connected and portrayed in ideologically biased documentaries.

Digging into narrative

“Façade,” released in 2005 by Michael and fellow artist-technologist Andrew Stern, represented a further extension: the first fully realized interactive drama. A person playing the experience visits the apartment of a couple whose marriage is on the verge of collapse. A player can say whatever she wants to the characters, move around the apartment freely, and even hug and kiss either or both of the hosts. It provides an opportunity to improvise along with the characters, and take the conversation in many possible directions, ranging from angry breakups to attempts at resolution.

“Façade” also lets players interact creatively with the experience as a whole, choosing, for example, to play by asking questions a therapist might use – or by saying only lines Darth Vader says in the “Star Wars” movies. Many people have played as different characters and shared videos of the results of their collaboration with the interactive experience. Some of these videos have been viewed millions of times.

As with “Terminal Time,” “Façade” had to combine technical research – about topics like coordinating between virtual characters and understanding natural language used by the player – with a specific artistic vision and knowledge about narrative. In order to allow for a wide range of audience influence, while still retaining a meaningful story shape, the software is built to work in terms of concepts from theater and screenwriting, such as dramatic “beats” and tension rising toward a climax. This allows the drama to progress even as different players learn different information, drive the conversation in different directions and draw closer to one or the other member of the couple.

Bringing art and engineering together

A decade ago, our work uniting storytelling, artificial intelligence, game design, human-computer interaction, media studies and many other arts, humanities and sciences gave rise to the Expressive Intelligence Studio, a technical and cultural research lab at the Baskin School of Engineering at UC Santa Cruz, where we both work. In 2014 we created the country’s first academic department of computational media.

Today, we work with colleagues across campus to offer undergrad degrees in games and playable media with arts and engineering emphases, as well as graduate education for developing games and interactive experiences.

With four of our graduate students (Josh McCoy, Mike Treanor, Ben Samuel and Aaron A. Reed), we recently took inspiration from sociology and theater to devise a system that simulates relationships and social interactions. The first result was the game “Prom Week,” in which the audience is able to shape the social interactions of a group of teenagers in the week leading up to a high school prom.

We found that its players feel much more responsibility for what happens than in pre-scripted games. It can be disquieting. As game reviewer Craig Pearson put it – after destroying the romantic relationship of his perceived rival, then attempting to peel away his remaining friendships, only to realize this wasn’t necessary – “Next time I’ll be looking at more upbeat solutions, because the alternative, frankly, is hating myself.”

That social interaction system is also a base for other experiences. Some address serious topics like cross-cultural bullying or teaching conflict deescalation to soldiers. Others are more entertaining, like a murder mystery game – and a still-secret collaboration with Microsoft Studios. We’re now getting ready for an open-source release of the underlying technology, which we’re calling the Ensemble Engine.

Pushing the boundaries

Our students are also expanding the types of experiences interactive narratives can offer. Two of them, Aaron A. Reed and Jacob Garbe, created “The Ice-Bound Concordance,” which lets players explore a vast number of possible combinations of events and themes to complete a mysterious novel.

Three other students, James Ryan, Ben Samuel and Adam Summerville, created “Bad News,” which generates a new small midwestern town for each player – including developing the town, the businesses, the families in residence, their interactions and even the inherited physical traits of townspeople – and then kills one character. The player must notify the dead character’s next of kin. In this experience, the player communicates with a human actor trained in improvisation, exploring possibilities beyond the capabilities of today’s software dialogue systems.

Kate Compton, another student, created “Tracery,” a system that makes storytelling frameworks easy to create. Authors can fill in blanks in structure, detail, plot development and character traits. Professionals have used the system: Award-winning developer Dietrich Squinkifer made the uncomfortable one-button conversation game “Interruption Junction.” “Tracery” has let newcomers get involved, too, as with the “Cheap Bots Done Quick!” platform. It is the system behind around 4,000 bots active on Twitter, including ones relating the adventures of a lost self-driving Tesla, parodying the headlines of “Boomersplaining thinkpieces,” offering self-care reminders and generating pastel landscapes.

Many more projects are just beginning. For instance, we’re starting to develop an artificial intelligence system that can understand things usually only humans can – like the meanings underlying a game’s rules and what a game feels like when played. This will allow us to more easily explore what the audience will think and feel in new interactive experiences.

There’s much more to do, as we and others work to invent the next generation of computational media. But as in a Marvel movie, we’d bet on those who are facing the challenges, rather than the skeptics who assume the challenges can’t be overcome.