On May 21, the airstrikes ended, the rockets stopped and the street fighting between Jewish and Arab Israelis abated as Israel and the militant Islamist group Hamas agreed to a ceasefire, ending the fourth war between them since 2008.

The war and the actions that culminated in it have been discussed extensively. Both sides have, as always, laid the blame for the latest hostilities at the feet of the other.

Sadly, this war and the lead up to it are just the latest entries in a long ledger written in blood and tears.

“Israel.” “Palestine.” One land, two names. Those on each side claim the land as theirs, under their chosen name.

‘Israel’

“Israel” first appears near the end of the 13th century BC within the Egyptian Merneptah Stele, referring apparently to a people (rather than a place) inhabiting what was then “Canaan.” A few centuries later in that region, we find two sister kingdoms: Israel and Judah (the origin of the term “Jew”). According to the Bible, there had first been a monarchy comprising both, apparently also called “Israel.”

In about 722 BC, the kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian empire, centred in what’s now Iraq. As an ancient geographic term, “Israel” was no more.

Judah alone

Less than a century and half later, Judah was overthrown. Its capital Jerusalem was sacked, the Jewish Temple destroyed and many of Judah’s inhabitants were exiled to Babylonia.

Following the exile’s end a little under 50 years later, the territory of the former kingdom of Judah served as the heart of Judaism for almost seven centuries (although the rebuilt Temple was again destroyed in AD 70, by the Romans).

‘Palestine’

In AD 135, following a failed Jewish revolt, Roman Emperor Hadrian expelled the Jews from Jerusalem and decreed that the city and surrounding territory be part of a larger entity called “Syria-Palestina.” “Palestina” took its name from the coastal territory of the ancient Philistines, enemies of the Israelites (ancestors of the Jews).

Subsequent to the Islamic conquest of the Middle East in the seventh century, Arab peoples began to settle in the former “Palestina.” Apart from about 90 years of Crusader domination, the land fell under Muslim control for just under 1,200 years. Although Jewish habitation never ceased, the population was overwhelmingly Arab.

Zionism and British control

In the second half of the 19th century, the longstanding yearning of Jews in the Diaspora to return to the territory of their ancestors culminated in the nationalistic movement called Zionism.

The Zionist cause was driven by steeply rising hatred toward Jews in Europe and Russia. Immigrating Jews encountered a predominantly Arab populace, who also considered it their ancestral homeland.

At that time, the land comprised three administrative regions of the Ottoman empire, none of which was called “Palestine.”

In 1917, the land came under British rule. In 1923, “Mandatory Palestine,” which also included the current state of Jordan, was created. Its Arab inhabitants saw themselves primarily not as “Palestinians” in the sense of a nation, but instead as Arabs living in Palestine (or rather, “Greater Syria”).

The State of Israel

Zionist leaders in Mandatory Palestine strove hard to increase Jewish numbers to solidify claims to statehood, but in 1939 the British strictly limited Jewish immigration.

Ultimately, the Zionist project succeeded because of global horror in response to the Holocaust.

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 181, partitioning the land into “Independent Arab and Jewish States.” The resolution met immediate Arab rejection. Palestinian militias attacked Jewish settlements.

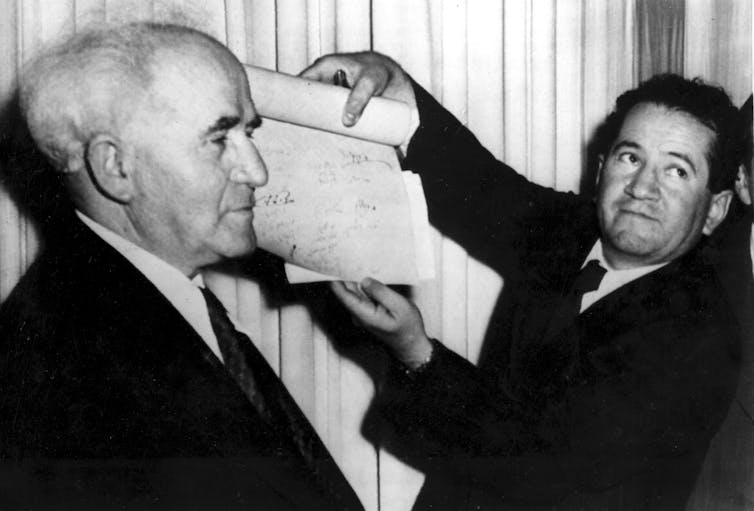

On May 14, 1948, the Zionist leadership declared the founding of the state of Israel.

‘The War of Independence’/Al-Nakba

The new Jewish state was immediately invaded by the armies of several Arab countries, alongside Palestinian militants. By the time the fighting ended the next year, the Palestinians had lost almost four fifths of their United Nations allotment. Seven hundred thousand of them had been driven from their homes, with no right of return to the present day.

For Jewish Israelis, it’s known as the “War of Independence.” For Palestinians, it was al-Nakba — “the Catastrophe.”

On Nov. 15, 1988, the Palestinian National Council issued a declaration of independence, recognized a month later by the UN General Assembly. Approximately three-quarters of the UN’s membership now accepts the statehood of Palestine, which has non-member observer status.

Diverging fortunes, constant hostilities

Despite multiple wars with Arab states and militant groups, Israel has flourished. Palestinians have struggled to establish functional governance and economic stability.

In the Six-Day War of June 1967, Israel repelled a true existential threat, routing a heavy Arab military force massed at its borders. Israel’s seizure of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza during the war has left Palestinians under various forms of painful Israeli occupation or control.

Throughout the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, many more Palestinians than Jewish Israelis have been killed and wounded, in part due to Israel’s advanced military capability but also to the well-documented Hamas strategy of situating command centres within civilian areas.

Jewish Israelis have experienced two violent Palestinian Intifadas (1987–1993; 2001–2005), the second of which saw a wave of deadly suicide bombings and ambushes.

In response, Israel erected its Security Barrier, which has essentially eliminated Palestinian terrorist attacks but added further to the pain of Palestinian civilians.

Since the 1990s, there have been several failed attempts to negotiate a two-state solution.

Under Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, Jewish settlement in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, viewed as illegal by much of the world, accelerated — making any future talks even more difficult.

Second-class citizens

About 20 per cent of Israel’s citizenry is Arab. Unfortunately, Arab Israelis are largely treated as second-class citizens within the officially Jewish state.

The recent defeat of Netanyahu could help to address this — Israel now has a governing coalition that includes an Arab Israeli party.

Taking stock

By more than 1,000 years, “Israel” predates “Palestine.” The land then became home primarily to an Arab population, again for more than a millennium. Both Jews and Arabs thus have a legitimate claim to the land.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has seen myriad wrongs and brutalities on both sides. No act of vengeance, however extreme, could now allow one party to say that accounts had been settled on their side.

The only way forward is, somehow, to cease looking backwards.

In an inversion of the Nile’s transformation in the Bible, the rivers of blood spilled must become water under the bridge.