The issues raised during Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial are a logical continuation of a presidency that pushed the limits of the American legal system. One of the arguments used by the former president’s lawyers was that freedom of speech as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the US Constitution covers not only his January 6 remarks but also his unsupported allegations that the 2020 presidential election was “rigged”.

For many constitutional law scholars, this is a “legally frivolous” argument because, in an impeachment trial, the president is not accused of a crime but of having violated his oath – in this case, by inciting an insurrection. However, it is a classic line of defense that Trump’s attorneys could take up in a civil or criminal trial.

Beyond this case, freedom of expression is a crucial question when seeking to understand events such as the white-nationalist demonstrations in Charlottesville in 2017, the protests by Black Lives Matter and “antifa” activists in 2019 and 2020, and even the pro-Trump mob’s January 6 attack on the US Capitol. It is also related to the out-sized prominence of personalities such as the late conservative right-wing host Rush Limbaugh and even the porn king Larry Flynt, both of whom saw themselves as champions of free speech.

American free speech: a unique but contested concept

For many Americans, freedom – especially freedom of speech – is the most cherished founding principle of the nation’s identity, and they see it is a tenet of American exceptionalism. It is true that the United States is different from other democracies in that it holds what is sometimes called an “absolutist” view of freedom of speech. In American law, even hate speech is protected, and the Supreme Court has repeatedly confirmed that there is no exception for hate speech in the First Amendment (Beauharnais v. Illinois, 1952; Matal v. Tam, 2017).

Former national legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Steven Shapiro calls the United States unique in this regard. He points to the country’s reservations on Article 20 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires signatories to prohibit hate speech, even though the US signed and ratified this international human-rights treaty in 1992.

Despite quasi-religious reverence for the First Amendment, the issue of freedom of speech is sometimes controversial even in the United States, as we see a rise in populism, increased political polarization, and an increase in provocative and extremist speech on social networks. In the words of Supreme Court Justice Kagan, freedom of speech has been politically weaponized. This has been done particularly by the conservative right and the alt right. Paradoxically, with the rise of white nationalism, it is now the more moderate liberals and the millennials who tend to support a measure of restrictions of free speech.

A chaotic history

The right to freedom of expression is almost as old as the United States itself. It is enshrined in the First Amendment ratified in 1791:

“Congress shall make no law […] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

From a strict literal perspective, free-speech protection thus initially concerned only laws passed by Congress. Over time, however, the Supreme Court extended this protection to other forms of governmental power, from the federal to local and across all three branches: legislative, executive and judicial. It should be noted in passing that the First amendment doesn’t address or prevent censorship imposed by private individuals and private businesses who can apply their freedom of commerce as they see fit.

Contrary to what is often assumed, the current interpretation of the First Amendment is relatively recent. For a long time, there were many restrictions to free speech. This was in part due to different societal norms, particularly in terms of sexual morality (see the Comstock Acts for instance). But there were also greater restrictions of political speech in what was considered interests of the State, like the Espionage Act of 1917. Thus, during the two world wars and at the beginning of the Cold War, the Supreme Court upheld judgments against dissidents who opposed conscription or advocated revolutionary socialism or communism (as in Schenck v. United States, 1919, or Dennis v. United States, 1951).

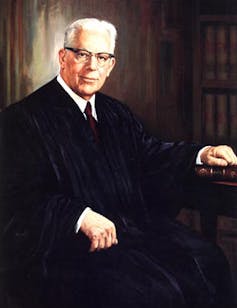

Everything changed with the Warren Court (1953-1969) due to a growing support for speech related to civil rights and the war in Vietnam. Paradoxically, the liberal interpretation of the First Amendment also provided protection for hate speech spurred by the Ku Klux Klan, as stated in Brandenburg v. Ohio, a 1969 decision that remains the standard for allowing extreme speech. Since then, freedom of speech in all its forms has generally been protected, including hate speech, unless there are specific exceptions.

The limits of free speech today

One of the lessons of the history of free speech in the United States is that standards are not set in stone. They do change as society changes and may yet change again.

Free speech is not absolute – US law does recognize a number of important restrictions to free speech. These include obscenity, fraud, child pornography, harassment, incitement to illegal conduct and imminent lawless action, true threats, and commercial speech such as advertising, copyright or patent rights.

Political speech, on the other hand, is one of the most protected categories. The Supreme Court even went so far as to conclude that campaign spending limits represent a violation of freedom of expression because it would restrict the financial means to express an opinion (as first ruled in Buckley v. Valeo, 1976, and then more recently and controversially in Citizens United, 2010).

As for the role that Donald Trump played in the months leading up to January 6 and on the day itself, the question still to be answered is the relationship between his false claims and harsh rhetoric and the attack on the US Capitol that immediately followed. Was his speech protected by the First Amendment? According to Brandenburg v. Ohio, freedom of speech allows “advocacy of the use of force” or “lawless acts” unless it is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and is “likely to incite or produce such action”.

Because these words can be up to interpretation, context is everything. The assessment of the context in which the insurrection took place will allow for what is called the “Brandenburg test” to determine whether Trump’s words were aimed at encouraging his supporters to commit a crime and advocating an offense that is both imminent and likely to occur.

A marketplace of ideas?

The Brandenburg ruling is important. It is what made it legal for neo-Nazis to march with swastika crosses in Charlottesville in 2017 or for Rush Limbaugh to use misogynistic, homophobic, racist and conspiracy-laden language during his long career. This decision is based on the principle that the competition of ideas in a free and transparent public discourse will allow people to freely decide what they want to believe.

This philosophy is exemplified in the metaphor of the “marketplace of ideas” used in a 1953 Supreme Court decision, which has since become a common analogy in American law. But what this metaphor also implies is that, as with any market, that of ideas is shaped by imbalances of power, particularly with respect to racial and financial inequality. Is the voice of Donald Trump really equivalent to that of the average citizen? And how do the biased algorithms of social networks allow a fair and free market of ideas?

Many Americans do not trust their government to regulate this marketplace of ideas. Yet the counter-examples offered by the European Union or Canada show that certain restrictions on freedom of expression are not necessarily incompatible with democratic principles.