In the last few months I’ve noticed a groundswell of murmurs about the internet’s relationship with culture. Again. But this time it relates to visual art. The discussion in terms of publishing is well worn (will e-Books decimate the print market?) and in music (is Spotify going to suck all life out of music?) – but as yet the visual arts have seemed to escape almost untarnished.

But now virtual art galleries are on the rise and prints are being sold en masse from massive online databases. And many are worried that the way in which we think about art will also inevitably change.

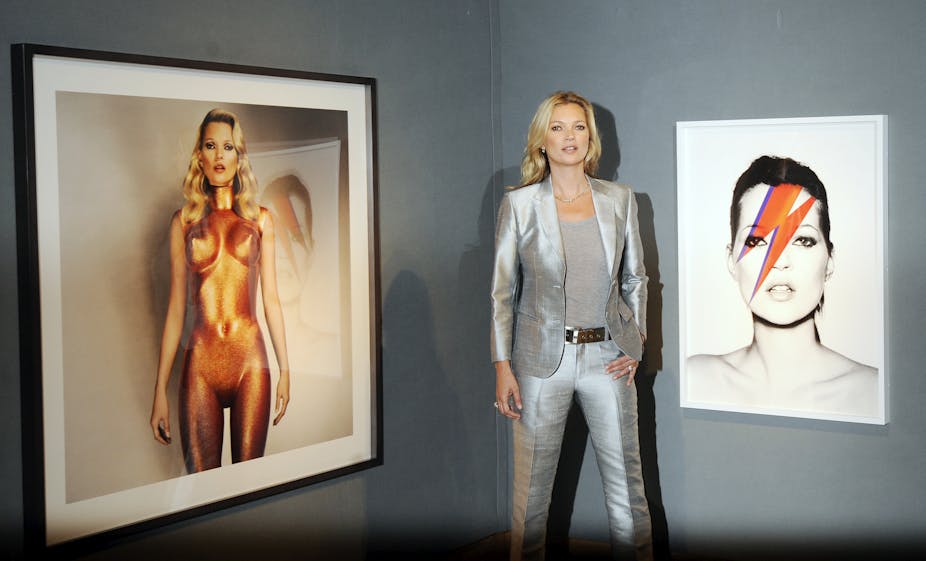

A couple of years ago Taschen published the book Kate Moss by Mario Testino, the limited edition of which was available for US$2,000. The book is an intimate photographic view into Moss’s life with so far “unseen” photographs and a personal essay by Moss herself.

Getting one of these was pretty difficult before the soft cover edition was published, as only 1,500 were printed. Each one was numbered as part of the edition and signed off by Moss. But of course, many of these images were already widely available on the internet. And we’re already snowed under by images of Moss, whether in adverts or the documentation of her exploits in the Evening Standard.

So why pay for an image that is already freely available within the public domain? Surely, many say, this wide accessibility of images through digital technology will change how we engage with “works of art”.

Let’s take the case of Easyart, which is a print business based in Newhaven, East Sussex. It has a licence to sell something like 60,000 images by 1,500 artists. The client is able to order the work online and it is subsequently printed to order in Newhaven on equipment developed for F1 racing car panels, mounted, framed and delivered.

In conjunction with Tate’s Matisse exhibition, the site offered 11 “original prints” of “rare Matisse lithographs”. Many have suggested that such wide availability of so many prints will fundamentally change how we engage with the art world, as both viewers and customers.

But this is typical hypochondria. The reproduced print is not such a new phenomenon, we have been debating about it for decades. John Berger’s four-part BBC series Ways of Seeing explored this very issue in 1972.

Much of the attention Easyart has received has focused on the fact that it has opened up access to art from Pablo Picasso to previously inaccessible collections of work, including botanical images from the Guardian and classic Hammer film posters. Chairman James Bidwell claimed it is set to become the “iTunes of art”.

Bidwell argues that his company is looking at the “democratisation of the art market” through its ability to provide customers access to art at reasonable prices. But the challenge with any attempt to democratise accessibility to classics of art is that art is not produced within a neutral vacuum. It is inscribed within a history of social and class distinctions, and in many cases inaccessibility actually increases its value.

Easyart sells a product that mimics an original work of art. Its products are not like typical print editions. Print editions, like Kate Moss’s book, have an indexical number indicating that they are a part of a finite edition. Their value is linked to the fact that only a certain number exist. Usually an edition print is signed by the artist, unlike the Easyart print, which is simply a reproduction.

So through the format of this infinite reproducibility, the very inaccessible nature of that original is perpetuated. An already mediated image is presented online to a private domestic sphere and from that sphere another mediated image is produced. Much like the stretched canvases available at IKEA, the Easyart print has already been extracted from any contextual referents.

In a 1936 essay Walter Benjamin wrote about how modes of technological reproduction was going to impact on autonomous aesthetic experiences. Benjamin was writing about many processes such as etching, engraving and Greek founding and stamping, but his focus was mainly on the advent of photography and film in the early 20th Century and on the distinction between the authentic original and its “copy”. He used the word “aura” to describe a set of characteristics that legitimised an “origin”. The reproduced image, he argued, has no aura. It has been removed from its location within time and space. Reproducing images, he argued, was going to fundamentally change how people engaged with art.

The anxiety that surrounded Benjamin’s writing on the loss of aura as a result of reproduction in 1935 is not dissimilar to the recent debates around the Easyart platform for purchasing prints. Certainly there is no aura surrounding an Easyart print, but that is not likely to impact on how viewers engage with contemporary art any time soon.

There is no doubt that print platforms will over the next few years carve out a market for itself as a slightly upgraded mode of wall decoration. But fortunately art has never simply been about pictorial images that adorn domestic and commercial spaces. Art today remains embedded within a whole system of historical, social and market relations. And so a move towards the “democratisation of the art market” today will require a shift in how art is produced, not simply how it is reproduced.