Our food systems are under increasing pressure from growing populations, diminishing resources and climate change. But, in a new report, we argue that city foodbowls – the agricultural land surrounding our cities – could supply more secure and sustainable food.

The final report of our Foodprint Melbourne project outlines a vision for “resilient city foodbowls” that can harness city waste to produce food, reduce dependence on distant sources of food and act as a buffer against increasing volatility in global food supplies.

But to do so we need to start planning now. Food is a basic human need – along with water, housing and transport – but it hasn’t been high on the planning agenda for Australia’s cities.

Growing food, and jobs

Australia’s city foodbowls are an important part of the nation’s food supply, particularly for fresh vegetables.

Melbourne’s foodbowl produces almost half of the vegetables grown in Victoria, and has the capacity to meet around 82% of the city’s vegetable needs.

Nationally, around 47% of highly perishable vegetables (such as lettuce, tomatoes and mushrooms) are produced in the foodbowls of the major state capitals, as well as eggs, chicken and perishable fruits such as berries.

New analysis by Deloitte Access Economics has shown that Melbourne’s foodbowl contributes A$2.45 billion each year to the regional economy and around 21,000 fulltime-equivalent jobs. The largest contributors (to the economy and to jobs) in Melbourne’s foodbowl are the fruit and vegetable industries.

Other research estimates that agriculture in Sydney’s foodbowl contributes around A$1 billion to the regional economy. The flow-on effects through the regional economy are estimated to be considerably higher.

City foodbowls at risk

City foodbowls are increasingly at risk. Our project has previously highlighted risks from urban sprawl, climate change, water scarcity and high levels of food waste.

Melbourne’s foodbowl currently supplies 41% of the city’s total food needs. But growing population and less land means this could fall to 18% by 2050.

Australia’s other city foodbowls face similar pressures. For example, between 2000 and 2005, Brisbane’s land available for vegetable crops reduced by 28%, and Sydney may lose 90% of its vegetable-growing land by 2031 if its current growth rate continues.

These losses can be minimised by setting strong limits on urban sprawl, using existing residential areas (infill) and encouraging higher-density living.

However, accommodating a future Melbourne population of 7 million (even at much higher density) will still likely mean we lose some farmland. The Deloitte modelling estimated this will lead to a loss of agricultural output from Melbourne’s foodbowl of between A$32 million and A$111 million each year.

Protecting our food supply

Australia’s city foodbowls could play a vital role in a more sustainable and resilient food supply. If we look after our foodbowls, these areas will strengthen cities against the disruptions in food supplies that are likely to become more common thanks to climate change.

The New Urban Agenda adopted in October 2016 at the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, or Habitat III, emphasises the need for cities to “strengthen food system planning”. It recognises that dependence on distant sources of food and other resources can create sustainability challenges and vulnerabilities to supply disruptions.

Resilient city food systems will need to draw on food from multiple sources – global, national and local – to be able to withstand and recover from supply disruptions due to chronic stresses, such as drought, and acute shocks, such as storms and floods.

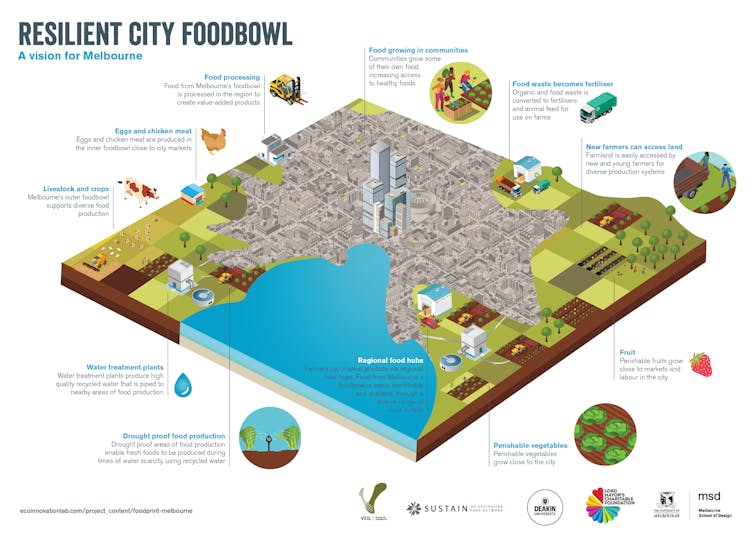

Our final report presents a vision of a resilient city foodbowl for Melbourne.

In this future vision, highly perishable foods continue to grow close to the city. City waste streams are harnessed to counter decreasing supplies of water and conventional fertilisers, and increased investment in delivery of recycled water creates “drought-proof” areas of food production close to city water treatment plants.

If Australia’s cities are to retain their foodbowls as they grow, food will need to become a central focus of city planning. This is likely to require new policy approaches focused on “food system planning” that addresses land use and other issues, such as water availability.

We also need to strengthen local and regional food systems by finding innovative ways to link city fringe farmers and urban consumers – such as food hubs. This will create more diverse and resilient supply chains.