Facebook is facing a reckoning in the court of public opinion for how the social media giant and its partners handle customer data.

In the court of law, holding Facebook responsible for its actions has been quite a bit harder.

CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been hauled in front of Congress to apologize for a data scraping scandal – a scandal that quickly followed an outcry that the site had been exploited by Russia during the 2016 election.

It’s rare to see a social media company pay consequences for its actions – or inactions – because of a broad immunity shield that some in Congress are rethinking.

The story starts 22 years ago. That’s when a defamation suit was brought by the now-shuttered investment firm Stratton Oakmont against the operator of an online discussion board. The name Stratton Oakmont may sound familiar. That’s because the brokerage was made infamous by Martin Scorsese’s “The Wolf of Wall Street.” The suit prompted Congress to protect the hosts of discussion boards – and, as it now turns out, social networking sites as well.

For the past four years, I’ve taught a college course that considers the importance of that law, the Communications Decency Act, in making today’s social media industry economically feasible. Arguably, that law created a climate in which the Facebooks of the world came to believe that anything bad happening to their users was someone else’s fault.

Let’s take a quick spin through the history.

‘Family-friendly’ internet

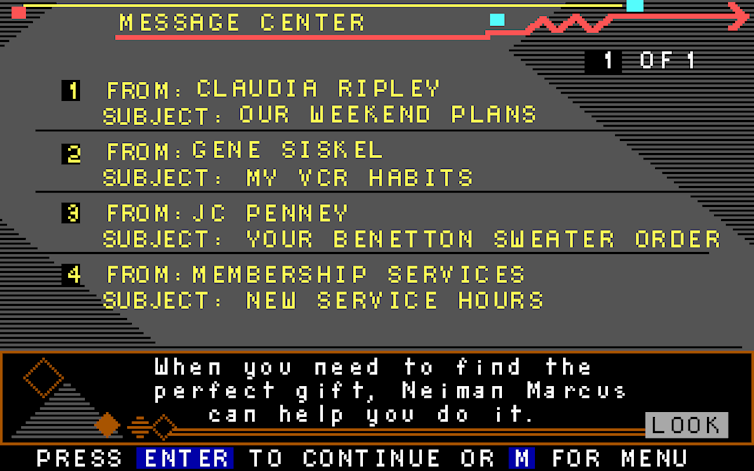

In 1984, Prodigy Communications Corp. launched as a pioneering entrant into the first rudimentary wave of internet service providers. To compete with much-larger CompuServe, Prodigy promoted its services as “family oriented,” promising to moderate pornographic material.

In October 1994, a commenter on a Prodigy discussion board posted a string of accusations about fraudulent stock offerings promoted by Stratton Oakmont. The commenter called the company “a cult of brokers who either lie for a living or get fired.” To anyone who has seen Scorsese’s film, this seems prescient and understated. Regulators shut down Stratton in 1996, and its founder went to prison for securities fraud.

Nonetheless, Stratton sued Prodigy for libel. In a 1995 ruling that shook the nascent industry, a New York judge ruled that ISPs could be held liable as “publishers” of their customers’ content. The judge wrote that Prodigy “held itself out as an online service that exercised editorial control over the content of messages posted on its computer bulletin boards, thereby expressly differentiating itself from its competition and expressly likening itself to a newspaper.” And like a newspaper, Prodigy could be sued over injurious material in reader submissions just as if the submissions were the company’s own words.

The ruling sent a worrisome message to the industry: Stop taking down harmful or offensive material, or you’ll be liable as the “publisher” of whatever remains.

Congress was alarmed.

Congress raises the deflector shields

Nebraska Sen. J. James Exon, an outspoken opponent of “cyberporn,” leveraged outcry over the Stratton case to help pass what became the Communications Decency Act. The CDA made it illegal to knowingly use internet services to transmit obscene material to minors. But Section 230 of the statute made two crucial concessions that – unforeseeably to Congress in 1996, seven years before the debut of MySpace – paved the way for the explosive growth of the social web.

First, the act holds only the actual creators of harmful content liable for its consequences.

Second, the act prevents liability for good-faith attempts to moderate “objectionable” material. This means immunity is not forfeited by removing offensive reader submissions. Today, this enables The New York Times to screen comments on its website without accepting liability for them.

In other words, Congress elected to treat the Prodigies of the world – eventually including Facebook – as no more responsible for the acts of their users than the telephone company. Just as AT&T is not liable for obscene phone calls placed by customers, neither an ISP nor any website with reader interactivity is the “publisher” of its users’ submissions.

Traditional publishers are liable for the consequences of the speech they print, even if that speech comes from outsiders who were neither paid nor solicited to submit. If The New Yorker carries a letter to the editor falsely calling someone a criminal, the magazine can be held liable alongside the letter writer. The theory is that the editors chose the letter and had the opportunity to fact-check it.

In this way, Section 230 represents a breathtaking recalibration of liability law. In effect, the online publishing industry has convinced Congress that its capacity to distribute harmful material is so vast that it cannot be held responsible for the consequences of its own business model.

To be clear, social media sites can still be liable for how their own employees mishandle user data, or for breaching promises made to customers in their terms of service, neither of which requires treating the sites as “publishers.”

The CDA is widely credited for the flourishing of YouTube, Yelp and other sites that rely on user submissions. It is also faulted for some of the social web’s worst excesses. Law professor Danielle Citron, author of the influential 2014 book “Hate Crimes in Cyberspace,” highlights how CDA immunity makes “revenge porn” possible by enabling websites to refuse demands to unpublish even the most intrusive content.

Those injured by reader-submitted content may still pursue legal action directly against the authors – if they can be found. A robust body of case law governs when a website host can be forced to “unmask” the credentials of its users. But – as with the Macedonians purveying “fake news” on Facebook – those authors may be beyond the reach of American courts, or lack the capacity to pay meaningful damages. That may leave those wronged with nothing but an earnest apology from a billionaire tech entrepreneur.