It is a commonly expressed belief that pro-environmentalists are different from the majority of the population. The stereotype has them as more left wing politically, more activists and generally more involved with society. But how does this stack up against reality?

In the Anatomy of Civil Societies Research Project, my colleagues and I have been coming up with data to answer just these sorts of questions. The project is not focused specifically on environmentalists, but the results looking at this dimension of individual citizens’ social priorities is telling.

In this project we have been systematically examining the social preference structures of large samples of citizens in Australia, the UK, the USA and Germany. Our report on Australia garnered significant press, particularly because it showed a dramatic decline in interest in environment-related issues between 2007 and 2011. However, this was not the original intent of the project, which was focused much more on examining the social, economic and political preferences of societies and those at the extremes in particular.

In delving deeper into this data one can see a very interesting set of differences between individuals. Here we are focusing on those people with very low environment-related preferences and those with quite significant environment-related preferences. These groups are important because, in many ways, these are the individuals who define the social debate on this topic. It is important to understand who they are in Australian society.

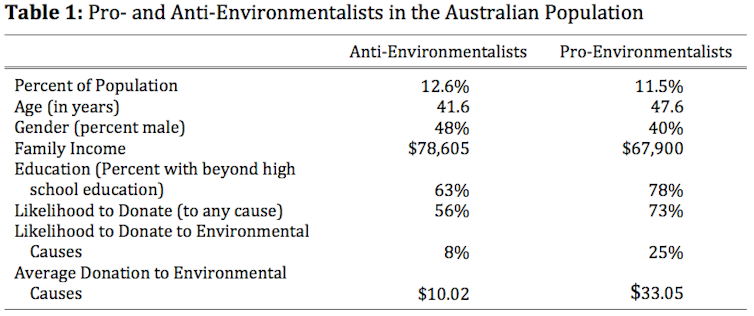

For simplicity in this article we concentrate only on the extremes (the general population being somewhere in between). The “anti-environmentalists” are those that rate environmental issues as last across the dimensions of social, political and economic issues that we examined. The “pro-environmentalists” are those that rate environmental issues as their top priority. Table 1 gives a picture of how they compare in our national sample of 1,508 Australians of voting age.

We see immediately some interesting differences and similarities. First, the two groups are approximately the same in terms of representation in the population. The pro-environmentalists are, on average, older, moderately less wealthy, more educated, more likely to give to charities and significantly more likely to give to pro-environment groups. What is interesting, however, is that their strong pro-environmental stance does not lead to overwhelming support for pro-environment civil society organisations. Seventy-five percent of those with very strong pro-environmental preferences do not give anything at all to pro-environmental organisations.

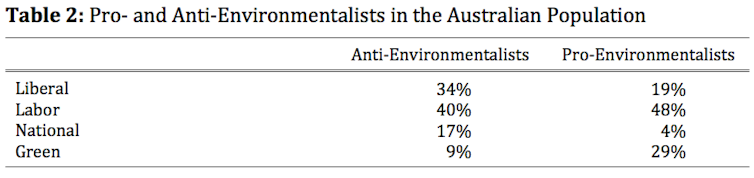

Table 2 outlines the voting likelihood of pro- and anti-environmentalists. This data is from the last Federal election. To keep the interpretation simple, we have shown these as the odds that someone would vote for one party over another given they were in the pro- or anti-environmental category.

Again, the results are interesting. Being a radical pro-environmentalist implies that you are very unlikely to vote for a Liberal-National candidate and much more so for a Labor or a Green candidate. However, it is not a natural given that a Green candidate would win out over a Labor candidate. In addition, anti-environmentalists are nearly as likely to support a Labor candidate as they are to support a Liberal candidate.

Having a pro-environmental preference means you are unlikely to support a Liberal-National candidate. But an anti-environmental preference is less informative, except in implying that you won’t support a Green candidate.

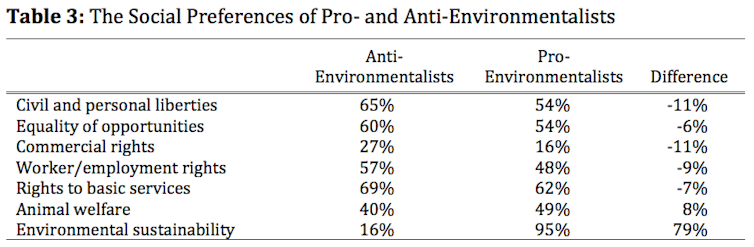

Perhaps the most interesting aspects of what we find in our results is the degree to which these individuals will trade off their pro- or anti-environmental preferences against other issues of social, political and economic importance. The table below shows the preference scores across 16 categories of issues (see our report for specific definitions and methods). One should interpret the scores on a 0-100 scale and as representing the percentage likelihood that the issue is salient to the individual.

Let’s first examine where there are no real differences – global security, global social and economic well-being, societal social and economic well-being, food and health, minority rights, rights to basic services, equality of opportunities, and animal welfare. It implies that in 10 of the 16 general social, political and economic categories, anti- and pro-environmentalists in Australia are not all that different.

In the one case where a big difference arises – commercial rights – the general concern for this category of issues is small for everyone. All we are seeing is that pro-environmentalists are simply even less concerned with commercial issues.

The three areas where we see big differences that matter are crime and public safety (where pro-environmentalists show significantly less concern), individual economic well-being and civil and personal liberties. Most telling is that pro-environmentalists are willing to sacrifice civil and personal liberties significantly to achieve environmental outcomes.

On the other side of the ledger, anti-environmentalists are much more likely to give up on environmental concerns to improve factors that influence individual economic well-being, such as the daily cost of living.

Our picture of the extremes of the environmental sustainability discussion is not quite so simple as it might otherwise seem. The lunatics on the left are not so different from the lunatics on the right.

But there are differences. These differences are most likely representative of very fundamental philosophical positions on two dimensions that we can phrase as questions. First, to what degree are you willing to give up something you care about for an environmental outcome? Second, to what extent do you believe that we need to constrain the rights of other individuals to an environmental outcome even when they don’t want to be constrained in their choices?