The aftermath of the 1934 Kalgoorlie riots, with their death toll of an “Aussie” and a “Slav”, the mass destruction of the homes of the Dings at Dingbat Flat and the rising horror in the town at how the alcohol-fuelled attack on foreigners had turned into sustained mayhem, points to an ambiguous anxiety that lurks at the heart of every Australian race riot.

For those caught up by a rising wash of righteous vengeance against the outsider, the emotion of indignant self-justification has to confront the wider awareness in the community of the fragility of civilisation, and of the importance of building bridges rather than moats between Australia’s many ethnic groups.

The TV documentary series The Great Australian Race Riot, which is being broadcast by SBS for the first three weeks of January, captures nine race riots that helped form Australia’s public culture. Episode One, which aired on January 4, explores the 19th century; Episode Two examines the first half of the 20th; Episode Three looks at the Second World War until the present.

Producers Essential Media have Peter FitzSimons, the bandana-ed popular iconoclast and author, marching across the Australian landscape, turning over rocks to find the remnants of the riots. Aided by a back-up team of historians, psychologists and a sociologist (I cannot lie, ‘tis I), FitzSimons begins at one of the least-known but perhaps most critical confrontations.

You can read in FitzSimons’ interpretation of the series an enthusiasm for a “good news” story. As he recognises on screen, there were more sombre outcomes.

Half a century after the British invasion, a mere decade after John Batman treatied with local Wurundjeri elders for rights to pay for the use of what would become Melbourne, the first re-organisation of the white power structure began. The English and Scots had imported into the new settlement the hierarchy of exploitation and suppression of the Irish that had characterised the home islands.

However, in the colony, the numbers of the ethno-religious groups were more equal. And in 1846, during an attempt to reassert the dominance of the Orange Order, the Irish Catholics revolted.

The authorities of the day already recognised that the social order could not be imposed in the same way it had been back in Ireland. The resolution to the violence saw the outlawing of discrimination against Catholics, a first step unique to the colony. It would also inexorably lead nearly 170 years later, after some enormous challenges, to the popular election of the first conservative party Catholic Prime Minister of Australia, Tony Abbott. Before Abbott, every Liberal leader had been a member of the Protestant ascendancy.

The series works from a basic proposition: that outbreaks of significant and violent social conflict point to a misalignment of power. What the government sees as the pathway forward sits out of kilter with deeper social inequalities. The late 19th century was a time of increasing racialisation of Australia. The multiracial population faced unequal opportunities, with very different skills, resources and perceptions of possible futures.

The two major anti-Chinese riots – at Buckland River in Victoria in 1857 and at Lambing Flat in NSW in 1861 – act as punctuation marks in the way “White Australia” would be inscribed on the landscape. The land would be defined as Australian in tension with Britain, especially after those British agreements with the Manchu Qing government that allowed the fairly free movement of Chinese citizens throughout the British empire.

Australia would be defined as “white” through the rapid intensification of racialised ideologies of superiority in the wake of the spread of social Darwinism and the affirmation of racial bigotry as an Australian social value – still apparently and unfortunately alive today in the mind of Attorney-General George Brandis. The 1857 and 1861 riots were driven by the perception among many European-Australian miners that the Chinese were present illegitimately and that their cultural capital gave them unfair advantages in exploiting increasingly scarce gold.

So while the 1846 riot helped establish the widened boundaries of who might be called “white” (now the Irish were allowed to wriggle into the cave), the mining riots ended up defining who could not be called Australian: anyone from Asia, but particularly the Chinese.

One of the few emotions that was widespread enough to be called “national” in the formation of the Australian nation was the belief that only Europeans carried enough of the civilising blood to draw up the terms and conditions for a Commonwealth of equality. Many Chinese were shocked and bemused by the self-delusion of the Australians, yet they still suffered the full weight of the racialised nation – one that at the end of the First World War was fully convinced it was White Australia.

After all, Gallipoli was the bloody baptism for future claims to Australia being a white man’s paradise.

Each of the riots that follows in the series charts how that problem – the delusional politics of race – would entwine Australia in conflict after conflict. The history stretches from days of attacks on the revolutionary pro- (and anti-) Soviet Russians of Brisbane, through the inter-Asian and anti-White confrontations of Broome, to that bloody series of clashes at Kalgoorlie.

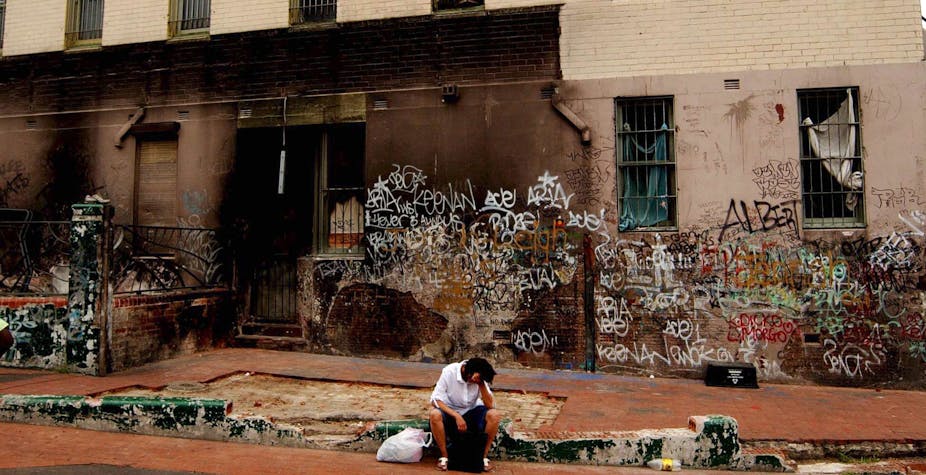

Even after the war to end racial hate concluded in 1945, White Australia did not dissipate. Italian immigrants, becoming Bolshie as the promised jobs failed to materialise and defined by their swarthy skin tones, were confronted with tanks and rifles at Bonegilla. Refugees, with their non-White ethnicities inscribed on their skin, were trapped in the relentless purgatory of Woomera until they tried to escape and were beaten back. The Indigenous population of Redfern finally struck back at perceived endless police oppression and violence.

These last three riots tell us that sometimes people have no recourse but to stand up against repressive authority – and sometimes we respect them and sometimes we fear them.

Afterwards, society may recognise the impossibility of their circumstances and the responsibility we all share to build those bridges and relieve that oppression. Or not. No denouement, only an open space for future painful exploration.

Episodes Two and Three of The Great Australian Race Riot will air on January 11 and 18 at 8.30pm on SBS ONE.