On the surface, the recent surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) suggests an urgent need to reform Britain’s relations with the European Union.

But polls tell a different story. The best data available is the monthly Continuous Monitoring Study (CMS), collected on-line by the British Election Study.

The CMS has detailed information on nearly 5000 UKIP supporters, more than any other single source, and has provided us with data from mid 2004 to the end of 2012, enabling us to examine how the motives of UKIP supporters have evolved.

What the data says

Surveys can sometimes be misleading when it comes to offering a respondent a list of options. Many voters may tick a box labelled “Europe”, if they are presented with one, but would not come up with the issue without prompting.

This can be a particular problem with issues like Europe which matter intensely to the political class, but are remote from voters’ everyday lives.

To avoid this problem, the CMS takes a different approach, putting up a blank text box and ask respondents to type in the issues they think are the most pressing. This approach can produce some comical responses - among my favourites are “Jamie Oliver”, “giant spiders” and “the lack of free cheese” - but on the whole people take the exercise seriously and respond honestly, giving us an insight into how voters see the political agenda, free from the influence of the survey taker.

The political agenda has shifted dramatically over the past eight years, so we break our data down into three periods: 2004-7, when Tony Blair was in charge and the economy was humming; 2007-10, covering Gordon Brown’s tenure and the onset of the economic crisis; and 2010-12, the years of Coalition government.

The tables below show how people surveyed responded during these periods.

Before the economic crisis (April 2004 - March 2007)

Economic crisis under Labour (April 2007 - April 2010)

The Coalition (May 2010 - December 2012)

Two clear messages emerge from these tables: in all three periods, UKIP voters have a distinct political agenda, but the EU is never at the top of it. In the latter years of Blair’s premiership, UKIP voters were most concerned about immigration, naming this more than twice as often as mainstream party voters, who were more concerned about security as Iraq and terrorism dominated the headlines.

In the early years of the financial crisis, all voters became more concerned about the economy, but UKIP voters remained more concerned about immigration, and also more prone to voicing populist hostility to the Brown government as their main political sentiment.

During the Coalition government, the same pattern has continued: UKIP voters now voice concerns about the economy more than any other issue, but still far less often than mainstream party supporters, who now think of little else.

Immigration remains an issue of intense concern for the Kippers, even as it has fallen away for other parties - and UKIP supporters remain the most prone to venting their spleen about the government rather than naming any substantive issues at all.

As for the EU, it certainly concerns UKIP voters more than others, but this isn’t saying much. Around one in five UKIP voters currently volunteers worries about Brussels as a primary concern, up from around one in eight at the height of the economic crisis.

By comparison the issue barely registers with mainstream party voters - less than one in ten Conservatives mention it, and tiny minorities of the other parties’ supporters.

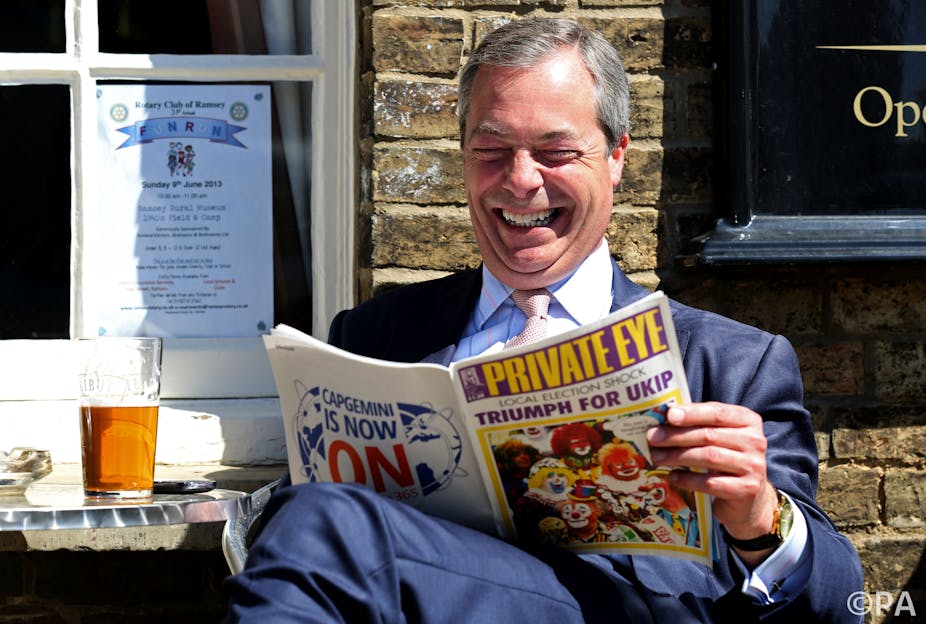

Given the agenda and priorities of his voters, Nigel Farage would be foolish to accept an electoral pact with the Conservatives over an EU referendum. UKIP has not surged to the top of the political agenda by mobilising a popular uprising against the EU; instead it is talking to deep-seated discontent with domestic issues such as immigration and the economy, and hostility to a political class seen as out of touch with the average voter.

A Conservative-UKIP pact won’t work

Given the domestic focus of UKIP voters’ concerns, a Conservative-UKIP pact over Europe would be little use to either party. The Conservatives would be unlikely to win over UKIP’s deeply distrustful voters, with a move that will smack of desperation and offer nothing on their domestic concerns. By doing a Westminster deal, Farage would lose his image as a populist hero, and many UKIP voters would depart in search of another outlet for their rage.

Farage and UKIP are much more likely to benefit by staying on the sidelines and watching the Conservatives tear themselves apart over Europe once again.

As David Cameron once recognised, “banging on about Europe” reinforces the notion that his party is divided and out of touch with the everyday concerns of voters man in the street.

By seizing upon UKIP’s rise as an opportunity to talk about nothing but referendums, pacts and Westminster manoeuvres, Cameron’s Eurosceptic colleagues risk reinforcing the appeal of their populist new competitor rather than addressing it.

Europe is not the source of the UKIP problem, and so Europe will not provide the solution.