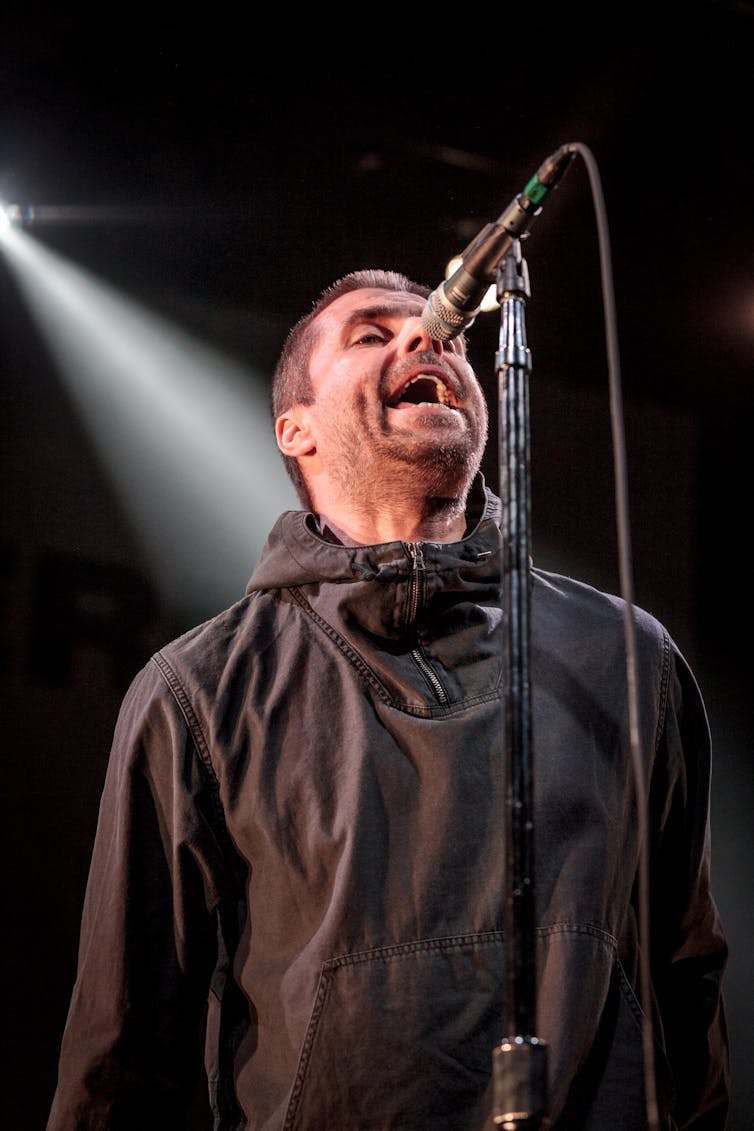

Liam Gallagher was in Toronto recently to perform songs from his solo album. As I took in the show, it all came back: The epic battles, still ongoing, between the infamous Liam and his brother Noel of the hugely popular ‘90s rock band, Oasis.

Oasis topped the charts globally with hits that included Champagne Supernova and Wonderwall. I was a fan and still am — the band’s music stands the test of time, and the seemingly endless feuds between Noel and Liam continue to capture our attention.

But 20 years after they first became rock 'n’ roll megastars, I have another take on the Gallagher brothers through my work as an associate professor of social work at the University of Toronto and lead investigator of Make Resilience Matter. Funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, it is a research, policy and practice initiative about children exposed to domestic violence.

So what does Oasis have to do with it?

We are learning that resilience can help kids “come through the fire” of domestic violence — an important finding, given what the Gallagher brothers faced then, and what children still face today. We are also learning that the Gallagher brothers’ exposure to domestic abuse could go a long way to explaining their continuing animosity towards one another.

Exposure to domestic violence equals abuse

Noel and Liam witnessed their father physically and verbally attacking their mother — they still recall her pain and humiliation. Noel has also talked about being beaten by his father.

However, through this adversity, I suggest that both brothers found escape — and, ultimately, resilience — through their music. Noel himself has stated that, as a teenager, the guitar he found lying around the house took him away from it all.

Music became the brothers’ lifeline. Liam’s performance in Toronto showed that resilience in action.

Music, in fact, as one form of healthy escape — along with other factors and processes we’ve identified in our research — can help put children on a pathway to resilience.

Why should we be concerned?

Today in Canada, children as young as infants experience what the Gallagher boys lived through. Exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) is a form of child abuse just like physical, sexual, emotional abuse and neglect.

The frequency of child abuse, including IPV exposure, has been well-established through large-scale studies in North America, such as the ground-breaking Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study in the United States. In Canada, exposure to IPV is the most frequently reported form of abuse with the latest Canadian census showing children living with violence in over half a million households.

Noel credited music as helping him escape

I shine a light on the Gallagher brothers’ story — as they themselves recount in their recent documentary, Oasis: Supersonic, and through media interviews — not to draw attention to the over-the-top rock star antics portrayed in the media, but to make a point about children, resilience and domestic violence.

Growing up in a social housing estate in Manchester, England, and on probation for truancy and stealing at 13, Noel discovered music, saying that it was his escape from everything, no matter what was going on at home or school.

Along with music, our research identifies other forms of “escape” such as sports, art, acting, writing and reading. As well, the strength and support of the boys’ mother Peggy, who ultimately left her husband with her sons, reflects another key finding in my research: Children need a safe, supportive adult/caregiver.

Through in-depth interviews with adults about their childhoods affected by IPV, we have gone on to identify 21 ways to resilience.

There’s significant research that tells us children exposed to IPV are more likely to experience trauma, aggression, depression and difficulties managing and expressing their emotions appropriately.

Seeing your mother hurt and living in a fear-filled house where everyone walks on eggshells, as the Gallaghers did, can cast a long shadow into the future: When children are exposed during critical formative years, it not only immediately disrupts important cognitive, social and emotional development, it also affects relationships and pathways into adulthood.

Research is also beginning to show — and I will be delving into this more fully in my own research — how sibling relationships can be affected: Some siblings may become over-protective, others may become distant, and still others may be hostile.

The antagonistic relationship between Liam and Noel immediately springs to mind.

Children can overcome their childhoods

There is good news, however, for the Gallaghers and others who grew up in homes plagued by domestic violence. Children can overcome significant adversity — many have. But they, and everyone surrounding and supporting them, need to know one thing: Resilience is not innate. It is not something one child has and another doesn’t.

It can be developed and fostered. (Visit our site for a full definition of resilience, with references.) Children who experience difficulties — sometimes severe problems — can adopt healthy relational behaviours, recover and follow healthy developmental trajectories.

Through our rigorous study of children and families facing extremely tough challenges surrounding domestic violence, we’ve found that resilience can be actively and intentionally promoted at three levels: The child, the child’s relationships and the context or the community that surrounds the child.

Many of these factors and processes can be developed, taught or strengthened by:

Encouraging a skill or talent;

Providing outlets and resources for kids to play sports, make music, act, etc.;

Connecting kids with safe, supportive adults and positive role models;

Assisting mothers in their efforts to protect their children from further harm by increasing access to support, housing, education, employment;

Involving supportive extended family;

Helping children accurately assign responsibility for the abuse and break the cycle of violence.

‘Through the fire’

For good reason, research and practice have focused largely on establishing the scope and addressing negative effects.

Now we’re learning that we need to more fully understand how children navigate their way “through the fire.” By better connecting the dots between children, intimate partner violence and resilience, we will improve how we identify and support resilience factors and processes for each and every child.

As for Liam and Noel Gallagher, there is still hope for their relationship.

Individually, they have navigated tremendous adversity. Despite their feuding via the media, given the desire, the right conditions and skilled intervention, there is still the possibility of reconciliation. Maybe their motivation could be what compels so many of us to do better — for our children.

For the Gallaghers, letting go of the anger and settling their differences might help stop the trauma and violence too often passed down from one generation to another — and encourage and support their own children’s resilience.