The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed hardship on millions of vulnerable Americans through unemployment and reduced work hours. And this has increased food insecurity across the nation.

There is no official figure yet for how many more families are struggling to provide regular meals around the table – the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s next annual report on food insecurity, defined as a lack of access to sufficient food due to limited financial resources, won’t be out until the fall.

But for me as an academic who has long tracked food insecurity trends, working out the increase in the number of people affected and projecting what will happen next is important. By understanding this, experts can work out whether what is occurring during the pandemic is likely to follow – or breaks with – previous patterns during and after economic recessions.

To project what has happened to food insecurity under the pandemic, colleagues at Feeding America, the nationwide network of food banks, and I used a model underlying the nonprofit’s Map the Meal Gap study. In particular, it looks at how changes in poverty and unemployment at a local level influenced food insecurity.

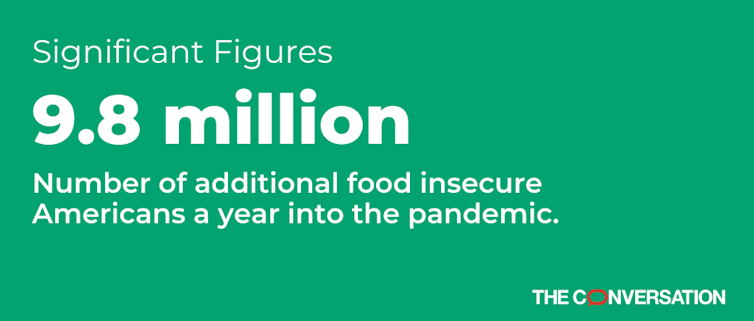

Our latest projection shows that the overall food insecurity rates rose sharply, from 10.9% in 2019 to 13.9% in 2020. In terms of people, that means a rise from 35.2 million food insecure Americans in 2019 to 45 million in 2020.

An additional 4.3 million children became food insecure over the same period, rising to 15 million in total. That represents an increase in the food insecurity rate for children from 14.6% to 19.9%, or a change from 1 in 7 kids to 1 in 5.

Based on our projections, we believe that U.S. food insecurity will decline slightly in 2021 to 12.9% for the entire population, and 17.9% for children. The reasons for this expected decrease include the impact of relief checks for many Americans – which has restrained the growth of poverty – and the continued decline in the unemployment rate after initial sharp increases in March and April 2020.

Meanwhile, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program , known widely as SNAP, continues to provide a lifeline for many Americans. Alongside these government programs, food banks across the country have rapidly increased their distribution of food to vulnerable households.

Finally, the agricultural supply chain in the U.S. has shown itself to be robust in the face of the pandemic.

To put the pandemic’s effect on food insecurity into perspective, the increases we are projecting for 2020 are less than what was seen at the outset of the Great Recession sparked by 2007’s financial crisis. Food insecurity rose from 12.2% (36.2 million people) before the Great Recession to 16.4% (49.1 million) at its peak.

Moreover, whereas it took several years after the Great Recession for food insecurity rates to drop significantly, we are projecting a decline in 2021.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Racial hunger gap

Even with this predicted decline in food insecurity in 2021, there are some troubling trends when we break things down by race, in particular for Black communities. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, the food insecurity rate for Black people was 19.3% – more than twice as high as it was for white Americans (9.6%). This projected gap narrowed somewhat in 2020. But in 2021, Black food insecurity rates are projected to fall by only 0.3 percentage points compared to a drop of 1.2 percentage points for white people.

This highlights a troubling trend. Namely, that food insecurity was a huge issue for the U.S. before COVID-19; it was a huge issue during the pandemic; and it will continue to be so after. And, in particular, those who are most at risk of food insecurity will continue to be especially vulnerable.

Monica Hake, Adam Dewey and Emily Engelhard from Feeding America contributed to this article.