Hugh Hefner, who died on September 28, was the founder of Playboy magazine. Playboy challenged repressive sexual norms and removed guilt around desire - it encouraged men to proposition women a little more. However, around 1970, when Playboy approached radical philosopher Herbert Marcuse for an interview, he gave them a proposition they weren’t expecting.

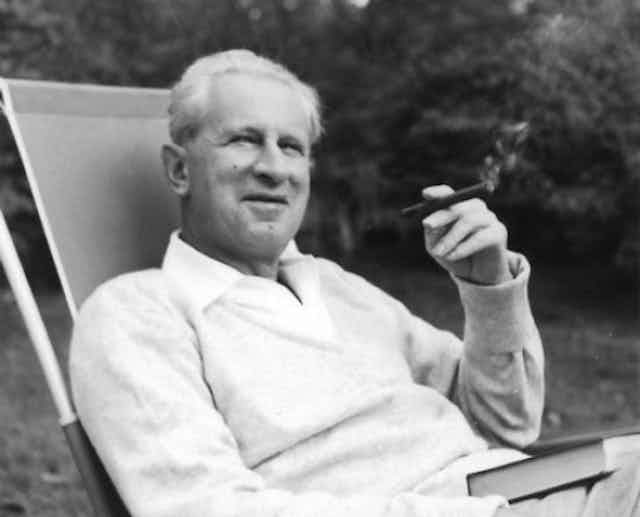

Marcuse had shot to fame across the US in the late 1960s. A German philosophy professor, who had emigrated in 1934 after fleeing the Nazis, Marcuse was at the grand age of 70 when Playboy phoned. He was highly articulate and measured, but also rather reserved.

His philosophy, on the other hand, was radical. He called for social transformation. He argued that, although liberal capitalist societies told themselves they were free and democratic, in reality they had pronounced authoritarian and imperialistic tendencies that had evolved alongside the ever-expanding market economy.

Marcuse famously argued that this led to a new kind of social pattern in which our deep drive for freedom and humanistic development was traded off for material comfort in an affluent society. By repressing our sexual desire, emotional expression and creative potential we had learned to “find [our] soul” in our “automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment”. This authoritarian pattern led people to become increasingly alienated.

Marcuse inspired student radicals across the western world through his writings and talks at rallies and demonstrations. Later, when famous, he reached even more people through TV interviews. Marcuse was viewed as the philosopher of sexual liberation. He embodied the zeitgeist in his argument that, despite material affluence, there were deep patterns of class, gender and racial inequality and exploitation. These were held in place via the repression of sexual desire, and of emotional and creative expression.

Given his new-found notoriety, it was only natural that Playboy wanted to do an interview with him. According to former student and friend Andrew Feenberg, Playboy had offered Marcuse “a large sum of money” for the interview. After receiving the call, Feenberg recounts, Marcuse considered the proposition carefully. His philosophy was one of radical social equality, which, for him, included a fulsome commitment to gender equality. As such, he decided “it was impossible for him to do it”. Whatever positive effects Playboy had in loosening over-repressive post-war sexual norms, it was part of a process that objectified and commodified women.

But instead of simply declining the offer, however, Marcuse told Playboy he would do the interview, but “only if he could be the centrefold”. The thought of the reserved old German professor, with his “long white hair”, “broad nose” and “enormous ears” (Michael G. Horowitz’s description) gracing the now iconic centre pages of Playboy in 1970 is definitely a rousing one. Unfortunately, the idea didn’t fly with the magazine.

But the way that the philosopher’s “joke” strikes us - simultaneously amusing and jarring - is precisely Marcuse’s point. Sexual desire is structured by social norms. Marcuse saw this as tending to objectify and commodify participants – in the case of Playboy, its readers and the women featured within it (the “bunnies”). In Marcuse’s view, this undermined the possibility of fully connecting our sexuality to our humanity.

While Playboy has had certain cultural effects that, within a limited historical context, can be seen as positive, Marcuse saw Hefner’s philosophy as a narrow and simplistic version of “liberation”, equating “anti-puritanism” to social freedom.

Heffner, via Playboy, did bring sexuality a little more into the open, in a context where that was sorely needed. And his contribution to various liberal causes, including civil rights, has rightly been praised in recent days. His simplistic sexual philosophy, however, is already something of a museum piece - historically significant in its way, but ultimately adolescent male fantasy.

It was a different story for Marcuse. Former student, Angela Davis, recalls that for his work in support of radical gender equality, one of the early organisations in the women’s movement took the extraordinary step of declaring Marcuse an “honorary woman”.

As for the male nude centrefold, the world had to wait until April 1972 when Cosmopolitan featured Burt Reynolds. A less surprising choice than Marcuse, Reynolds deeply regretted the decision, believing it had negative effects on his career.