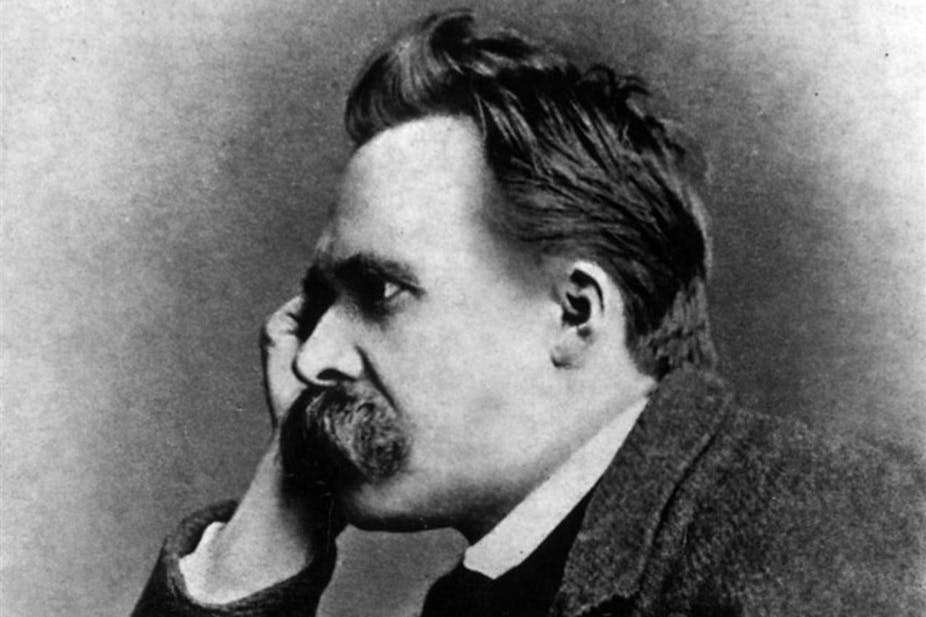

The morning of the US presidential election, I was leading a graduate seminar on Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of truth. It turned out to be all too apt.

Nietzsche, German counter-Enlightenment thinker of the late 19th century, seemed to suggest that objective truth – the concept of truth that most philosophers relied on at the time – doesn’t really exist. That idea, he wrote, is a relic of an age when God was the guarantor of what counted as the objective view of the world, but God is dead, meaning that objective, absolute truth is an impossibility. God’s point of view is no longer available to determine what is true.

Nietzsche fancied himself a prophet of things to come – and not long after Donald Trump won the presidency, the Oxford Dictionaries declared the international word of the year 2016 to be “post-truth”.

Indeed, one of the characteristics of Trump’s campaign was its scorn for facts and the truth. Trump himself unabashedly made any claim that seemed fit for his purpose of being elected: that crime levels are sky-high, that climate change is a Chinese hoax, that he’d never called it a Chinese hoax, and so on. But the exposure of his constant contradictions and untruths didn’t stop him. He won.

Nietzsche offers us a way of understanding how this happened. As he saw it, once we realise that the idea of an absolute, objective truth is a philosophical hoax, the only alternative is a position called “perspectivism” – the idea there is no one objective way the world is, only perspectives on what the world is like.

This might seem outlandish. After all, surely we all agree certain things are objectively true: Trump’s predecessor as president is Barack Obama, the capital of France is Paris, and so on. But according to perspectivism, we agree on those things not because these propositions are “objectively true”, but by virtue of sharing the same perspective.

When it comes to basic matters, sharing a perspective on the truth is easy – but when it comes to issues such as morality, religion and politics, agreement is much harder to achieve. People occupy different perspectives, seeing the world and themselves in radically different ways. These perspectives are each shaped by the biases, the desires and the interests of those who hold them; they can vary wildly, and therefore so can the way people see the world.

Your truth, my truth

A core tenet of Enlightenment thought was that our shared humanity, or a shared faculty called reason, could serve as an antidote to differences of opinion, a common ground that can function as the arbiter of different perspectives. Of course people disagree, but, the idea goes, through reason and argument they can come to see the truth. Nietzsche’s philosophy, however, claims such ideals are philosophical illusions, wishful thinking, or at worst a covert way of imposing one’s own view on everyone else under the pretence of rationality and truth.

For Nietzsche, each perspective on the world will have certain things it assumes are non-negotiable – “facts” or “truths” if you like. Pointing to them won’t have much of an effect in changing the opinion of someone who occupies a different perspective. Sure enough, Trump’s supporters were apparently unperturbed by his poor performance under the scrutiny of fact-checkers associated with the mainstream and/or liberal media. These forces they saw as irretrievably anti-Trump in their perspective, with their own agenda and biases; their claims about the truth, therefore, could be dismissed no matter what evidence they cited.

So if Nietzsche’s age has arrived, what should we expect living in it to be like? According to him, perhaps not as miserable or futile as we might think.

Even if he was right that all we have to go by are our different perspectives on the world, he didn’t mean to imply we are doomed to live within the limits of our own biases. In fact, Nietzsche suggests that the more perspectives we are aware of, the better we can be at reaching a watered-down objective view of things.

At the end of his 1887 book On the Genealogy of Morality, he writes:

The more eyes, different eyes, we know how to bring to bear on one and the same matter, that much more complete will our “concept” of this matter, our “objectivity” be.

The presidential election saw two sides utterly immersed in their own perspective, each refusing to acknowledge any validity in the opposing view. The idea that social media exaggerate this and create an echo chamber has now entered the mainstream. But if we really are living in Nietzsche’s post-truth times, we can’t rest within our own perspective, assured that, in the absence of an objective truth, our truth will do.

Listening to the other side and taking it into account – seeing the world through as many eyes as possible – is now more important than ever.