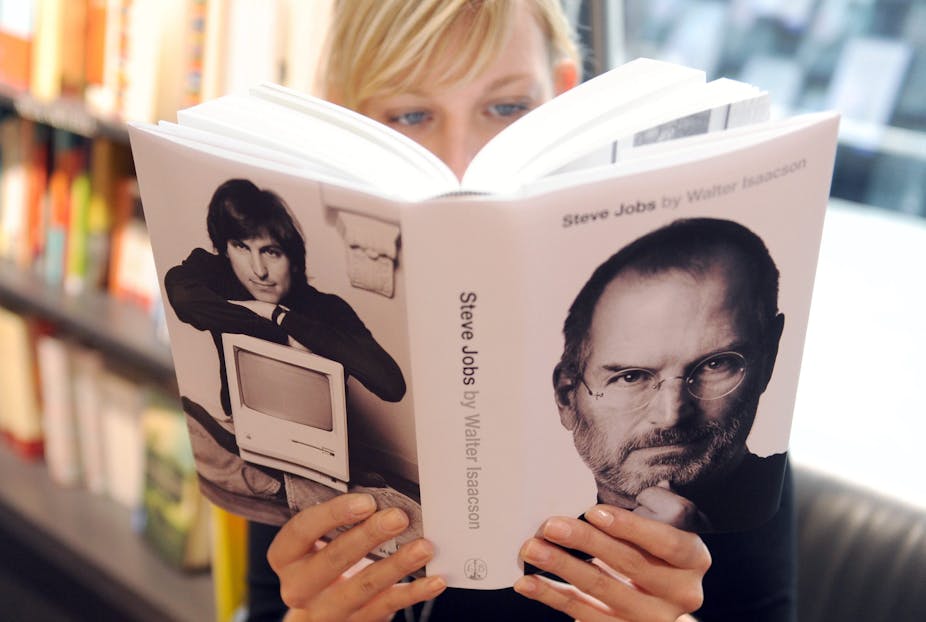

Steve Jobs’ “official” biography was always going to be a bestseller, with its promise of a candid examination of the inner workings of the world’s most successful salesman and the company he twice built.

And his death shortly before the book’s release has fuelled the public’s desire for his life story. Many readers are approaching the biography as a 656-page obituary.

But why did Jobs choose a biographer to narrate his life rather than pen his own story?

Unveiling the secrets

On the day of his death, tributes permeated the web at 10,000 tweets per second, or faster than you can say genius. Pre-orders for Isaacson’s biography soared.

The next day Isaacson’s publishers, Simon & Schuster, brought forward the release date of the biography by nearly a month.

While the well-worn trope of the rags-to-riches American success story has proven appeal, part of the allure of an “official” biography of Jobs (Isaacson’s is not the first biography, nor will it be the last) is the expectation of getting the inside story on Apple.

Jobs made secrecy an integral part of the company’s marketing strategies and manufacturing policies, as a plethora of rumours sites such as MacRumors, AppleInsider and Stupid Apple Rumors attests.

The culture of secrecy that was cultivated by Jobs and continues to be enforced throughout the organisation is severe.

The public, while not usually interested in the development and manufacture of most products, is hungry for the truth behind Jobs’ keynotes.

Biography or autobiography?

One would have thought that for a megalomaniac such as Jobs, an autobiography would have been more fitting.

But by allowing a biographer to take control, Jobs gains the historical, cultural and literary capital of biography and avoids the reader’s assumption of spin doctoring.

All technological products are ephemeral: Jobs undoubtedly wanted something more enduring.

The designated biographer

In the last interview Jobs gave to Isaacson he explained that his motivation for putting his life on the page was for his children to “know” him.

While this may be true, there is a danger in relying too much on the subject, especially one as savvy as Jobs.

This is where biographical marketing terms such as “official” or “authorised” should be treated with some scepticism.

To be clear, Isaacson does not use either term in the title of his book. Instead he is what Deirdre Bair describes as the “designated biographer”. That is, the biography is written with the cooperation of the subject yet is not censored by the individual or the estate.

As Jobs’ wife, Laurene Powell, told Isaacson, “He’s good at spin, but he also has a remarkable story, and I’d like to see that it’s all told truthfully.”

Isaacson leaves it to the reader to assess whether he succeeded in his “mission” or not.

The power of posterity

Unlike a CEO or a marketing executive, biographers make lousy spin doctors.

They are often better suited to tearing their subjects apart than celebrating them.

As Oscar Wilde wrote, “Every great man nowadays has his disciples, and it is always Judas who writes the biography.”

While the subject of biographies is considered to be of the greatest importance (almost all bookstores arrange the biography section by subject rather than by the biographer’s surname) it is easy to overlook how biographers portray or market their subjects for better or for worse.

In the seventeenth century, artist biographers Giovanni Baglione and Gian Pietro Bellori used biography to trash Caravaggio, which resulted in a devaluing of his art for more than two centuries.

More people read James Boswell’s Life of Johnson than any of Dr Johnson’s many and varied works.

William Blake was singlehandedly resurrected by an 1863 biography by Alexander Gilchrist titled The Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus” [Unknown Artist].

Biography has the power to re-create, sustain, redeem or resurrect its subjects.

While memoir abounds with minor lives, biography remains an elitist genre. For more than 2,000 years it has been dedicated to the successful, the powerful and the famous.

Herein lies the power and possible abuse of biography.

Jobs’ intended gain from choosing Isaacson to record his life story was not financial but for posterity, which is perhaps his final keynote of all.