When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded its work almost four years ago, it provided a road map for Canadians to follow. That road map, the 94 Calls to Action, aims to “revitalize the relationship between Aboriginal Peoples and Canadian society” after more than 100 years of the traumatic and systemic removal of Indigenous children from their families.

Call No. 43 underpinned all others, according to the commission. The commission urged federal, provincial and territorial governments to fully implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They called it “the framework” for all reconciliation measures “at all levels and across all sectors of society.”

It’s extremely rare for international human rights standards to even be mentioned in the Canadian policy debate. However, when Canada voted against the declaration in 2007 at the United Nations, it was the first time that Canada had ever stood in opposition to an international human rights standard.

It remains today the only international human rights standard in Canada up for debate.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper issued an official apology for residential schools in 2008. However, my ongoing study on state apologies to Indigenous Peoples demonstrates that apologies without clear policy shift are typically rejected as “empty gestures.”

International standards of justice require that those responsible for human rights violations must do more than acknowledge and apologize for the harm that has been done. They must go further. They must take every reasonable measure to set things right and to prevent any recurrence of harms.

A closer look at the history of the declaration and its unique framework for human rights protection underscores the TRC’s wisdom in highlighting its indispensable role in reconciliation.

The birth of the declaration

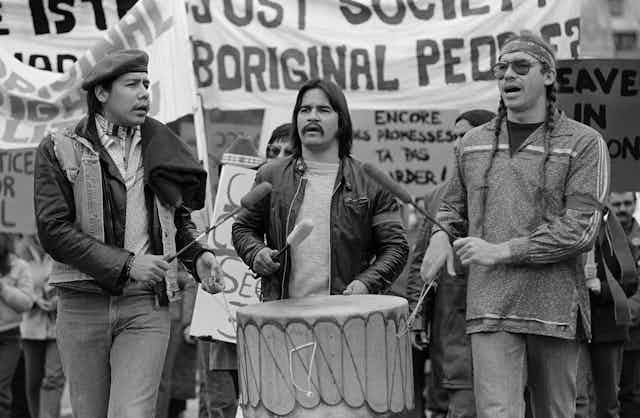

The idea for an international standard on Indigenous Peoples’ rights emerged out of several grassroots Indigenous movements in North America. Those movements were informed by their connections to traditional Indigenous forms of governance. They were also influenced by the U.S. civil rights movement, as well as decolonization movements across the Global South.

Fed up with government policies and frustrated by the lack of neutral avenues for dispute resolution, these Indigenous movements took their cause to the international level, hoping to appeal to wider global consciousness on human rights.

Indigenous diplomacy at the UN in Geneva and New York carved out a unique space where Indigenous peoples could actually sit down with states and jointly create a mutually agreed framework for recognition, protection and fulfilment of our rights. The process of developing the text for declaration began with the creation of a special working group within the UN human rights system in August 1982.

This was the first time that the direct beneficiaries of a global human rights instrument standard were also its co-authors. On Sept. 13, 2007, a full 25 years after the writing process began, the UN General Assembly adopted the declaration as a body of “minimum standards” that all states are expected to uphold.

The very length of this process — a quarter-century! — tells us a lot about the depth of resistance that Indigenous peoples had to overcome to bring the declaration to life. It also speaks volumes about the dedication of all those Indigenous advocates from around the world who returned to the UN year after frustrating year until eventually, they prevailed.

As Dalee Sambo Dorough, now president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, said during the final years of the negotiation process:

“I truly would love to just be at home enjoying my rights, and not having to pound the halls of the United Nations to gain a little respect, to gain some recognition of my inherent rights as an Indigenous woman, or the collective rights that I share with my people.”

Refuting the doctrines of racial superiority

Human rights lawyers and scholars often say the declaration creates no new rights. They say they have been developed on the foundation of other international human rights standards with vast global experience in their interpretation and application.

But, as I have written in my book, Global Indigenous Rights: A Subtle Revolution, the specific way the declaration approaches these existing rights is subtly revolutionary. The declaration’s approach helps to transform the often Eurocentric discourse of human rights to more fully encompass Indigenous worldviews, histories and contemporary struggles.

With the adoption of the declaration, the famous words “We the peoples of the United Nations” at long last became inclusive of the realities of Indigenous Peoples. It made way for Indigenous Peoples who seek a multiplicity of new relationships with UN member states within whose boundaries our territories and nations have been divided and subsumed.

The declaration reinvigorates the themes of self-determination, decolonization and anti-discrimination that are the foundations of the United Nations.

In its preamble, the declaration refutes the doctrines of racial superiority that have been used to justify the dispossession of Indigenous peoples around the world. In its provisions, the declaration calls for concrete remedies for the harms that have resulted from this dispossession.

Reconciliation: Much work needs to be done

For more than 10 years, I have been attending various international meetings such as the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues that support the ongoing work of implementing the declaration. I am also working with Indigenous academics and other partners around the world to share knowledge and experience about the growing body of implementation measures at the national and regional levels.

While the era of UN declaration implementation is well underway, enormous work remains to be done. This is as true of Canada as it is of the rest of the world.

The declaration calls for redress and rights protection through a wide range of specific provisions on matters such as Indigenous languages, cultural property, sacred sites, traditional medicines, environmental protection and the rights of children and families. More than anything, however, the declaration recognizes Indigenous Peoples’ continued authority, as self-determining peoples, over decisions affecting our lives and futures.

James Anaya, a former UN special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, has said the declaration’s foundation in established human rights obligations, the direct involvement of Indigenous peoples in its development and the exhaustive deliberations that led to its final adoption give the declaration a unique “moral, political and, yes, legal” weight that makes its implementation all the more imperative.

In 2018, the House of Commons passed a private member’s bill, Bill C-262 — put forth by NDP MP Romeo Saganash — meant to create a legislative framework for federal implementation of the declaration. Key provisions of the bill included review of federal laws and direct collaboration with First Nations, Inuit and Métis people in establishing policy priorities. These measures are key to meaningful implementation by the federal government.

The story of Bill C-262 is bittersweet, however. The House of Commons adopted the law, which was further supported by a unanimous motion in the House. These facts give some hope of seeing the legislative framework adopted in the future.

In the end, however, the opportunity to pass the legislation in the current session of Parliament was lost because the bill was stalled by Senate filibustering.

This highlights the considerable remaining resistance, much of it partisan, to the concrete implementation of the declaration.

For this to change, more people must take the time to learn about the declaration. More people need to see their way past the myths and misrepresentations that confuse its actual content and implications. More people need to join the ranks of those who have already championed the UN declaration — an indispensable part of the national project of reconciliation.