The Anglo-Australian artist Sidney Nolan was among the most renowned of his generation. Buried in Highgate cemetery in London, he was seriously prolific, completing more than 40,000 works in his lifetime, the most famous of which are of the Australian outlaw Ned Kelly and his gang.

The past few months have been important for Nolan’s fan base, taking in first the centenary of his birth in 1917 and then the 25 year anniversary of his death in 1992. But while commemorative events were taking place in the UK and Australia, my research led me to concentrate on a more specific part of his back-story.

Between 1942 and 1944, Nolan served in the Australian army. Stationed in home territory in north-west Victoria, his main job was guarding emergency food supplies. In 1944, however, on finding out that he was to be sent to the jungles of Papua Guinea to fight the Japanese, he absconded.

After Nolan later moved to London and became a big name in the art world, the royal family became keen buyers of his work. In 1981, he duly received a knighthood. During my research, I became fascinated by the contradiction between Nolan’s wartime desertion at a time when Australia was a British dominion, and later receiving such a high honour from the Crown. Did the British establishment know what it was doing – and, if so, why was the knighthood allowed to go ahead?

The Nolan story

Sidney Nolan’s work was far from consistent. His friend the Australian art critic Robert Hughes once wrote:

I have known artists whose work was uneven … but I have seldom known one whose output had such highs and lows as Nolan’s, such extremes of crap and lyrical near-genius.

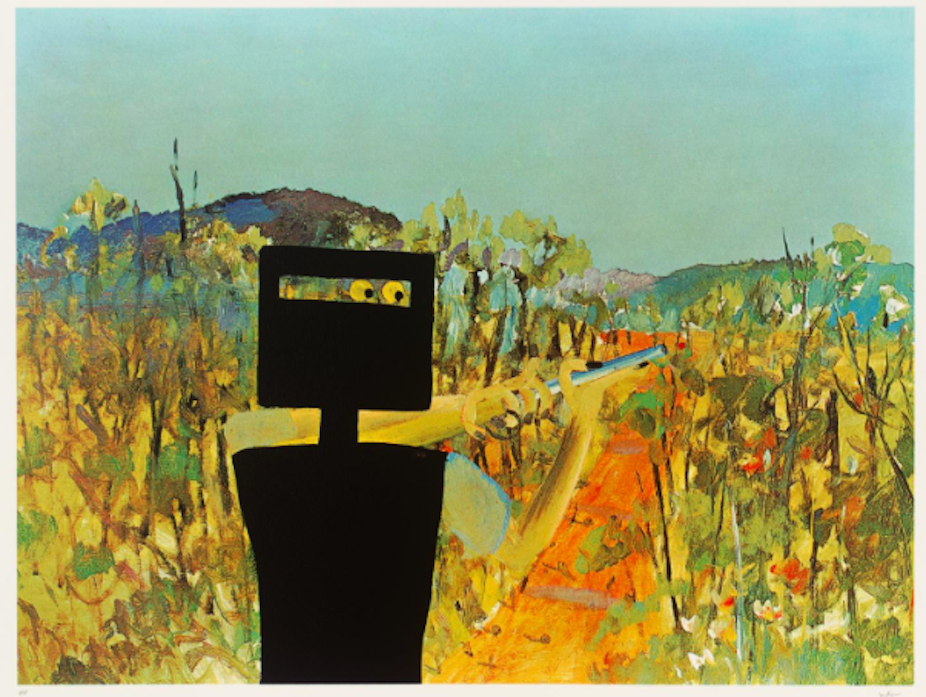

Collectors have paid handsomely for the prodigious output over the years, with Nolan’s First Class Marksman painting of Ned Kelly (see main image) most famously fetching £3.3m in 2010 at an auction in Sydney.

Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings have held their appeal despite – or because – of their faux-naif qualities. Kelly was the Irish Australian outlaw who became Australia’s anti-hero when he was hanged for killing policemen in 1880 – despite a petition for clemency with 30,000 signatures.

The First Class Marksman painting depicts Kelly’s last stand at Glenrowan in Victoria, when he kitted out himself and his gang with suits of armour made from metal plough boards. With the police closing in, Kelly ungallantly corralled 60 hostages in the Glenrowan Inn. But the police smoked out the gang, shooting Kelly in the feet and taking him to Melbourne to be hanged.

Nolan would complete his first paintings of the outlaw when he too was an absconder, lying low at Heide near Melbourne in 1944 in a ménage à trois with his patrons Sunday and John Reed. When the military police came to look for him, as they did from time to time, Nolan – according to Robert Hughes – would allegedly put on a dress to pose as a girl.

Hughes wrote:

[Nolan] would struggle into one of Sunday Reed’s dresses and wander about in the pasture by the creek with a staff, muttering to himself, the candid blue eyes staring. ‘It’s just me crazy kid sister’, Reed would explain. ‘She likes to look after the geese.’

Curiously enough, Nolan had copied this trick from Steve Hart, a member of Ned Kelly’s gang. One of Nolan’s Kelly paintings is even entitled Steve Hart Dressed as a Girl.

In 1948, Nolan received an amnesty for deserters and was discharged in absentia from the army. He subsequently fell out with the Reeds after marrying John’s sister Cynthia and went to Sydney, where the British art historian Kenneth Clark visited his studio and encouraged him to ship out to London.

Nolan followed Clark’s advice and within a year of arrival sold his first painting to the Tate. He moved to the British capital when the era of major shows with major dealers was in full swing for Australian artists who had come to Europe. Nolan would be based in the UK for most of the rest of his life.

By the time he was knighted, Nolan had become a mainstay of the British cultural establishment. Nonetheless, awarding such high honour to a wartime deserter could easily have caused a media storm – and he was also appointed Commander of the British Empire in 1963, received the Order of Merit in 1983 and Companion of the Order of Australia in 1988. I was curious to find out more.

When I submitted a freedom of information request to the UK Cabinet Office about any honours awarded to deserters in the 1980s, I was told they didn’t “hold the information you requested”. This left me unclear as to whether the Main Honours Advisory Committee was aware of Nolan’s desertion or not – and information around particular honourees is protected by the Data Protection Act 1998.

I was later told however that: “Each case considered by the committee is looked at on its individual merits … I can assure you that probity is taken very seriously.” On this basis, it is hard to believe that a matter like Nolan’s desertion would not have come to light. Decisions to strip knighthoods from the likes of Robert Mugabe and Fred Goodwin certainly suggest the committee is very sensitive in controversial matters.

We may never know for certain what members of the committee were thinking when they commended Nolan. Perhaps it was felt that he was exonerated by the amnesty in 1948. But at a time when the horrors of World War II were still a relatively recent memory, this might have seemed cavalier to many. Ultimately Nolan’s admirers may not care, but it’s an intriguing footnote into the life of one of the most fascinating artists of our times.