When Britain declared war on Germany on August 4 1914, there had been a very long period of relative peace in Europe, stretching almost a century from the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815. There were wars, but they were regional ones: bloody but limited.

Before 1914, few suspected that a great war was approaching. People knew that the complex web of European alliances meant that any conflict between two great powers would escalate to engulf the entire continent. Because such a war would be suicidal, many thought that it simply wasn’t an option. Anti-war writer Jan Gotlib Bloch published a book in 1898 called Is War Now Impossible? And war was not viewed lightly where it did occur – the international reputation of Britain during the Boer War (1899-1902) and of Italy during the Libyan war (1911-1912) were very low. So war was by no means seen as a legitimate tool of politics; then, as now, it needed a very good explanation.

But there was a different rhetoric of war at play, which made all the difference. Children in both Germany and the UK were taught to be willing and ready to fight for their “fatherlands” and to make the ultimate sacrifice, for example by learning Horace. The famous line “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (how sweet and honourable it is to die for one’s country) was later bitterly mocked as “the old Lie” by Wilfred Owen in his 1917 poem. The poem describes a soldier’s miserable death after a poison gas attack.

German author Erich Maria Remarque’s famous war novel All Quiet on the Western Front has the same topic, attacking teachers who praised the sacrifice for the fatherland and pressured their pupils to volunteer.

But the feeling that this form of patriotism was wrong only surfaced during and after the war. World War I was the watershed between widespread patriotism and the broken, distrustful attitude towards war we have seen across Europe ever since.

Patriotism and glory

Before 1914 the relationship between the armed forces, war and “fatherland” were different. War was considered to be terrible, but also glorious. Soldiers had high social prestige – nowhere more so than in Germany, after three wars of unification, which ended in 1871.

The military was an integral part of everyday life. All continental European armies were conscripted, and so every able-bodied young man had to serve two years (three in France) in the armed forces and take a subsequent place in the reserves. In the days before radio or television, military parades and concerts were part of everyday entertainment.

The biggest mass organisations in Germany before 1914 were not political parties or trade unions – it was the regional veterans’ organisations. Together, they had almost 3m members – nearly 5% of the German population at that time.

Soldiers and former soldiers were highly respected members of society across Europe. The Prussian minister of finance, Adolf von Scholz, considered his promotion to the rank of lieutenant in the reserves the happiest day of his life – this might not seem very odd – until you learn that he was already minister of finance.

In Germany, the recent wars of unification created a particular atmosphere. Those who had fought in the wars looked back on their glorious deeds with pride. Their successors felt somehow that they were not quite real soldiers until they had fought a war, and were therefore eager, in this sense, for action. And this sense of proving self-worth, living up to one’s elders, is something seen across Europe.

Naturally, it is difficult to measure soldiers’ love of war for war’s sake. In writings after 1918, many of these explosive opinions were omitted, or replaced in retrospect by more legitimate reflections.

The die-hards

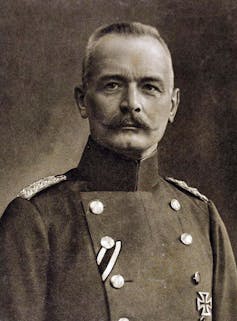

But we can get an idea of the views of a political die-hard by examining a letter written in March 1912 by Erich von Falkenhayn, shortly before he became Prussian war minister and, subsequently, in September 1914, chief of staff.

The letter, written in March 1912 after the second Moroccan crisis and during the Libyan War, shows how Falkenhayn passionately wanted war, for some political, but mainly for private reasons. Writing on September 30 1912, he predicted that all the European powers would suffer, and “the USA and Japan would easily gain the upper hand in the event of a great European war”. Despite this, he hoped that war would break out regardless, concluding: “For me it will be all right. I am most tired and extremely bored by this lazy peacetime life.”

In August 1914, when he saw the cheering crowds in Berlin, he said to German chancellor Bethmann Hollweg: “Even if we perish, it will have been wonderful.”

Falkenhayn was a warrior who wanted war because he wanted to prove he was a valuable soldier. And it’s not too hard to find similar opinions. The Prussian Ministry of War was full of cheering officers at the moment of mobilisation; full of joy, they shouted and embraced each other.

We can find similar attitudes in other countries. Winston Churchill, who in 1914 was First Lord of the Admiralty, reflected on suicide after the moderate Serbian reply to the Austrian ultimatum. He said: “If war can be avoided, I lived for nothing.”

Writing to his wife on 28 July 1914, he said:

Everything tends towards catastrophe and collapse. I am interested, geared up and happy. It is not horrible to be built like that? The preparations have a hideous fascination for me. I pray to God to forgive me for such fearful moods of levity.

And while Falkenhayn, after the sobering experiences of trench warfare, became from autumn 1914 more cautious and was looking for peace, Churchill was, despite the disaster of Gallipoli, still enjoying war. He wrote in a letter in 1916:

I think a curse should rest on me – because I love this war. I know it’s smashing and shattering the lives of thousands every moment and yet, I can’t help it, I enjoy every second of it.

These were extreme opinions held by a minority. But we could mention the Italian futurists or the warmongering poet Gabriele D’Annunzio as even more extreme examples. And civilians understood soldiers’ eagerness for action. In 1914, German foreign minister Gottlieb von Jagow said dryly: “Soldiers who dream of peace are an absurdity.”

Today, military personnel in all countries may be ready to go into battle in the hour of need, and some may dream of action – like the firefighter who hopes for a fire to fight. But most soldiers I know – and I’ve met many – are not eager.

The war that began a century ago was a cultural watershed. It changed our attitudes towards war. Our ideal of heroes shifted from the bellicose Greek-Roman model to more peaceful ones. Today’s heroes are people such as Gandhi or Mandela, whose characteristic is the refusal of violence.