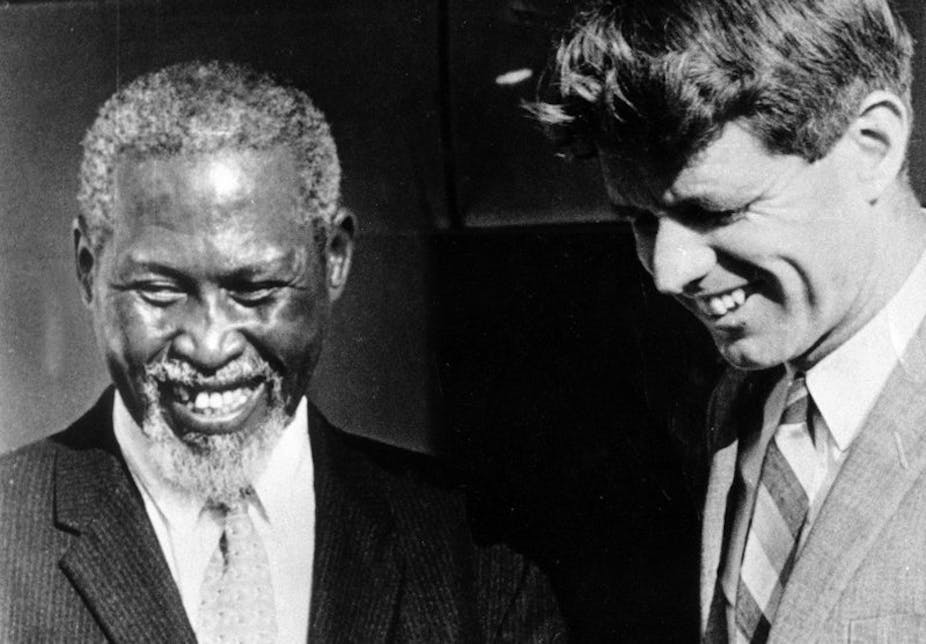

“RFK in the Land of Apartheid: A Ripple of Hope” was recently screened at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) with filmmaker Larry Shore on hand to discuss the film. The documentary chronicles American Senator Robert Kennedy’s visit to South Africa in 1966, recording many historical moments around his short visit, including the defiant meeting with then African National Congress (ANC) President Chief Albert Luthuli, then under a banning order. Known by his initials, “RFK” was part of the famous Kennedy political clan. He was assassinated in 1968.

The speeches Kennedy gave at the universities of Cape Town, Stellenbosch and Wits may have faded from public memory or may no longer seem relevant. However, by recovering these images, the film succeeds not only as a record of the racial segregation of this society and the former “whites-only” universities at the height of apartheid, but acquires an added poignancy with the recent student protests and ongoing calls for the transformation of the entire education system in South Africa.

Kenneth Kaplan, who teaches directing and writing in the Film/TV division at Wits University in Johannesburg, interviewed Shore, who is a Professor in the Department of Film & Media Studies, Hunter College, New York.

Why did you choose to focus on this particular event?

I was a junior high school student in Johannesburg in 1966 when Robert Kennedy visited South Africa. Although I did not attend any of the events, I followed it closely in the liberal Johannesburg English-language newspapers like the Rand Daily Mail and The Star. The visit really amazed me, as it amazed many others. In high school and then at the University of the Witwatersrand I became really interested in American history and politics, which included an interest in the Kennedys.

I remembered the visit when I left South Africa in 1973 for the US and afterwards. My MA included a good dose of US foreign policy, and policy towards Africa and apartheid South Africa in particular. So I think I was always interested in US-South Africa relations and the connections between the two countries. I also teach about this stuff as a professor at Hunter College in New York. This carried over when I became interested in documentary films.

I also liked the story because it opened up doors to other interesting stories that deserved to be told, like those of Albert Luthuli and the National Union of South African Students (Nusas), to name just two. I am very grateful and pleased that the film has been well received by South African audiences although my original primary audience was the United States. I always believed that it helps to tell a story about a foreign country to an American audience if it has an American connection. Robert Kennedy was that connection.

What impact did the visit have and how did it shape relations between the US and South Africa?

As a filmmaker you don’t want to overdo it or make more of it than is right. It was only a moment – but it was an important moment. I do think that the visit did have an impact in South Africa. It was the first time anyone important had come to the country from the outside world and said they were on the side of those who opposed apartheid. And it was someone important – a Kennedy and brother of President John F Kennedy, who was popular in South Africa. He was not just a famous American.

South Africans were interested in American affairs and they believed Robert Kennedy was going to be the next president. And you had the feeling that this important person was going to do something about it when he went home. Or at least tell the world what was happening in South Africa and maybe something would happen. Like the famous speech he gave at the University of Cape Town, his visit was a “ripple of hope” and it was felt across the country.

His visit with Chief Luthuli was a big publicity boost for the ANC, which in 1966 was in the depths of the deepest repression with Nelson Mandela on Robben Island and Luthuli banned to Groutville (a small town in the province of KwaZulu-Natal). The visit to Soweto and RFK’s meeting with various black South Africans was a lift for black South Africans.

It also was a source of encouragement for white liberal organisations and individuals within Nusas, liberal politician Helen Suzman and others. I think that the visit to Stellenbosch University helped lay a few seeds for what later became the verligte (enlightened) movement among Afrikaners. I don’t think the visit changed US policy towards South Africa directly at the time, but it was one of a number of things that began to bring attention to bear on South Africa – what was going on there and what could be done about it.

What might we know about you and your life that you think led you to make this film?

Well, as I said before, I have always been interested in US-South African stories. Certainly a part of that is because I am a South African-American. I have lived most of my adult life in America but I grew up in and have a lot of connections to South Africa. I kept that connection during my years in the anti-apartheid movement in the US and after the end of apartheid. When I became convinced that it was a good story, and would make for a good film, I realised that, as someone who understood and had lived in both countries, I was well suited to make the film.

What are some of the creative challenges you faced making the film?

I think one of the most difficult things about making a film about someone as famous as Robert Kennedy is to avoid hagiography – putting him up on a pedestal and making the visit appear more important than it was yet at the same time not denying its significance. How to find the right balance was a major challenge in making the film.

As with any documentary like this, I also faced challenges deciding what interviews not to use. I had lots of terrific interviews with important and interesting people but I had to leave some of them out and make tough selections.

The text above has been edited from an interview conducted by Kenneth Kaplan with Larry Shore following the recent screening of “RFK in the Land of Apartheid: A Ripple of Hope” at Wits University.