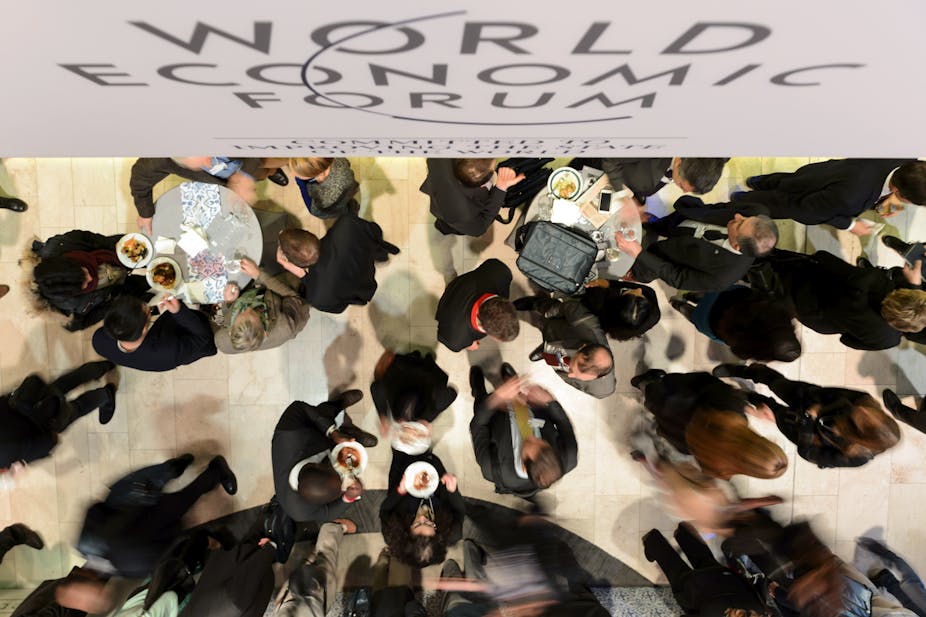

Last week, the 0.1% met at World Economic Forum annual gathering in the Swiss mountain resort of Davos. While the official excuse to go there is to discuss and shape the global agenda – the theme dominating this year being inequality – we know that it is more about networking, socialising, fine dining and, new for this year, a chance to improve your wellbeing.

The wellbeing agenda

After receiving a ticket (at an average cost of US$40,000), participants were issued with a pedometer and challenged to walk more than 6km a day – a bicycle would then be donated to a child in need in Africa.

There were also sessions on mindfulness, during which participants spent ten minutes sitting in silence meditating (some of the more impatient members left to take calls halfway through the meditation session). The conference had its own workplace wellness app, they got the chance to listen to rapper Will.i.am talking about the benefits of wearable technologies. There was also a report by the consultants Bain and Co which examines the positive financial benefits of investing in wellbeing.

Is it a mere coincidence that this trend booms at a time when the inescapable issue of the conference agenda is the staggering inequality in the world? In the 1970s Christopher Lasch claimed that in the wake of the political turmoil of the 1960s (the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal), many people had lost faith in politics, instead focusing on individual projects, such as “eating health food, taking lessons in ballet or belly-dancing” or “immersing themselves in the wisdom of the East, and jogging”.

When people no longer believe in political transformation, an appealing alternative is individual transformation. When the world cannot be changed for the better, we put all our energies into improving ourselves.

Davos pre-recession

When the sociologist Richard Sennett visited the annual meeting in Davos in 1998, health and wellness were not on the agenda. After spending some time in conference rooms, champagne receptions and ski slopes, Sennett began to realise that the defining feature of the Davos men was their flexible nature. With this attitude, they would not look at tumultuous changes in life circumstances as a threat, but as an opportunity to be relished.

The “Davos man”, as Sennet calls him (no mention of a her), is someone who constantly reshapes their profile and rebrands their persona. They would not define themselves exclusively by what they do because they always work on more than one project. They could be discussing government policies and developing a new technology, while in the next moment, marketing catastrophe bonds, contemplating a pop music career and skiing high above the mountain resort.

This ability to live many lives at once and be uncertain about anything seemed to be underpinned by a capacity to let go of your past. If you were a state bureaucrat in the past, that didn’t matter. That was the past. What mattered was the latest technology or the newest innovation in the financial markets.

This flexible nature also made it easy to forget about the basic existential questions of the majority of people on earth. But the Davos man is not completely unaware of the bitter feelings this nurtures of the great mass of humanity living below the snow-line. According to Sennett, whenever the Davos man begins discussing the people who are “left behind”, they become distinctly uncomfortable and start fidgeting. Clearly they recognised the existence of the 99% who are not so comfortable with building their lives on the shifting quicksand of entrepreneurial capitalism.

Much has changed since Sennett ventured into the mountains in 1998. We have been through numerous financial meltdowns, an extended campaign of war in the middle east, a series of global uprisings against untrammeled globalisation, the overthrow of many dictators and much more.

A changing world

Just as the world has changed, so too has Davos. The elite who descend on the Magic Mountain no longer display an indifferent attitude, but radiate with compassion and purpose. At the meeting, social responsibility is at the top of the agenda. Shying away from the people who are “left behind” has also faded. Instead of nervous fidgeting, participants at the WEF put global inequality top of the agenda.

Yet how much of this talk is sincere and how much is it part of the participants convincing themselves that they are on the right side of history? Like Sennett’s Davos man, the new wellness men are concerned about their moral appearance. If being a flexible high-achiever was the aspiration then, now it is to be compassionate, healthy and spiritual.

Contemporary politics is getting taken over by the wellbeing agenda. This could have many upsides: who could argue against better healthcare, cleaner environments and more exercise? However, the way it is often used tends to turn away from these more structural issues and uses wellbeing as a badge of being a member of the new global elite.

To be a Davos man now does not just mean waxing lyrical about the powers of the free market – you also need to frequently check your steps on your fit-bit, spend some time in a mindfulness class, work out at the same time as you network, deal with global inequality and work out how market solutions like “pandemic bonds” might help to solve Ebola.

The ideal solution for bringing this altogether for our new nomadic elite is of course the latest management fad – the walking meeting. That way they can burn off the champagne, network and also build up steps on their pedometer, which will allow a child in Africa to have a new bicycle.