In the much-trailed Channel 4 documentary, Things We Won’t Say About Race That Are True, Trevor Phillips argued that a British disinclination to have controversial conversations means certain issues related to race aren’t being discussed.

Phillips, the former chairman of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, said that people need to be “more ready to offend each other” and to talk about things that are true, even if they are difficult subjects. He even suggested that doing so might save children’s lives. Through this hour-and-a-half of tough talking, we learnt that Britain’s Jews were indeed rich and powerful and that various ethnic groups were more likely to commit certain crimes than others.

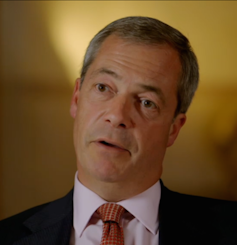

In what will probably be the most remembered part of the programme, UKIP leader Nigel Farage criticised anti-discrimination legislation, arguing that we should now live in a “colour-blind” society – and indeed that in many ways we already do.

The fact that Farage thinks this way no doubt merits discussion. It’s perhaps even a clear example of what straight talking on race can yield. But all in all, I was left feeling that the analysis put forward by Phillips was unconvincing. Much of the programme’s content was undermined by the false premise that race is under-discussed and needs liberating from a veil of well-meaning silence.

For me, the problem started early on. While the title of the programme purported to offer a discussion of race, Phillips’ analysis avoided the term for the most part. It actually focused on discussion about cultural and ethnic difference.

The idea of racial difference is considered so problematic in scientific and social-scientific analysis that Phillips, it seems, wasn’t really prepared to go there. And the fact that he did not makes the decision to lead with the word “race” in the title of the programme seem sensationalist. It offered little to the actual discussion Phillips thinks we need to have, which was mostly about ethnicity.

Frankly, I am far from convinced that this discussion has been as absent from British society as the programme suggested. As we approach the 2015 election, I expect (as usual) that racial discussion will be all too prominent as parties battle each other to talk toughest on asylum and immigration and about the rights and wrongs of British multiculturalism.

And race, of course, is not just for election times. In the tabloid press, in social media, on radio and television, racial issues seem ever-present to me.

There are, of course, subjects raised in this programme that do merit further attention. Problems of segregation and integration, feelings of political abandonment among white working classes and the under-representation of black football managers, are all important issues, but handling them in a sensitive way is not a matter of political correctness or political censorship but of common sense.

As Simon Woolley, a current member of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, tried to caution his old colleague on the programme, discussions about race need to be mindful and smart. Otherwise they too easily provide fodder for racists.

The argument that Britain’s Jews are disproportionately rich and powerful is a case in point. Taken as a whole, it can indeed be said that this group is successful. But that fails to take account of the wide diversity of real Jewish lives, many of which are not stories of wealth and influence.

And there are several other ethnic groups (not to mention social groups) that have been similarly successful in statistical terms. Research suggests that the children of many other migrant groups are more likely to end up in professional or managerial roles than their white counterparts from similar social backgrounds.

The prioritising of ethnicity in this analysis silences very important issues of class, which better explain different social outcomes. It is an analysis that also silences the history of racism. Jews have been labelled as rich and successful in societies where that is the case, but more often in societies where it isn’t. Only when we think about the role that racism has played in our construction and analysis of Jews, will we come closer to understanding this community and community-relations in general.

I am not convinced that championing the success of Jews outside of the historical context, and without consideration of class and other communities, can contribute to any productive discussion of race relations – that goes for the other groups discussed in this programme too.

Similarly, on the matter of crime statistics, I am left wondering about the point that Phillips really wanted to make. Having explained how upsetting and exasperating his relationship with the police had been as a black motorist, he then seemed to nonetheless advocate racial profiling in policing if it could be driven by accurate data.

Perhaps I missed the point, but is it really smart to suggest that a force that has been judged to be institutionally racist, that Phillips himself has experienced as racist, should be encouraged to think racially when it comes to crime?

Overall, I ended up feeling that this programme misfired. No doubt British multiculturalism remains a work in progress and talking about issues of ethnicity and cultural difference is important.

But in a country in which racism is rife, and in which scaremongering about race and immigration is prominent in the media and in politics, I would question whether a sensationalist programme of this nature is likely to improve the situation.