Just how big are the stars?

Earth feels quite big, what with it taking an entire day to fly between Sydney and London, and clearly the sun and moon are quite large in the sky.

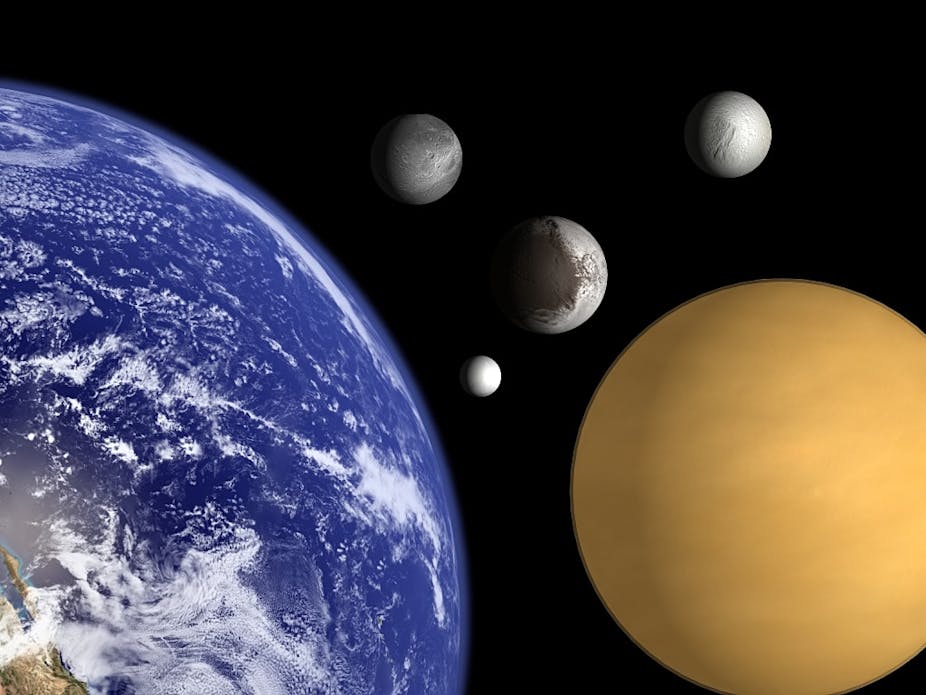

But with virtually everything else appearing as little more than points of light, it is difficult to appreciate just how enormous our cosmic companions really are.

We have long appreciated the sizes of the planets, with the realisation that Earth shares the solar system with giants and dwarfs.

While Venus is practically a twin of Earth, at least in terms of size, how do we visualise the other planets?

Let’s start with an everyday orange. A little experimentation reveals the one in front of me, right now, has a diameter of eight centimetres.

So if this orange represents Earth, how big are the other planets?

The smallest, Pluto (and to me, Pluto will always be a planet) would be about 1.5 centimetres across, slightly smaller than a five cent coin.

At the other end of the scale, Jupiter – the largest planet in the solar system – would be 90 centimetres across: the size of a large beach ball.

Try putting a five cent coin, an orange and a beach ball next to each other, and you will appreciate the scale of the planets.

But as we will see, the stars put the planets to shame.

Let’s start with our own star, the sun. Due to a lucky coincidence, we can keep the props on the table, but with the orange now representing Jupiter, and the beach ball representing the Sun and its almost 1.5 million kilometre diameter.

On this scale, the radius of Earth is relegated to less than one centimetre, half the size of your five cent coin.

The sun sounds immense, but its classification as a G-Type dwarf suggests it may not be as impressive on the stellar scale.

Small

How small can stars get? It turns out the smallest stars – the red dwarfs – are the most common, making up more than half of all stars.

In fact, one of the closest stars to our sun, Proxima Centauri, is such a star.

These stars feebly burn their nuclear material, living for 10 trillion years, and will be the last lights to go out in the dim and distant future universe.

While they are more than 80 times the mass of Jupiter, the intense squeezing of gravity ensures their radius is about the same as the planet, and so representing our sun as the beach ball, a red dwarf would be the size of the orange.

Large

What about in the other direction, towards the largest stars? Stars are born from collapsing gas clouds and ignite when the pressures in their cores begin to transmute hydrogen into helium.

This represents stability in the life of a star, and it spends the majority of its time in this state; technically, the star is said to be on the Main Sequence.

The most massive Main Sequence stars, the O-stars, are enormous – 40 times the mass of the sun – with a surface temperature of 40,000 degrees celcius.

In terms of size, these stars are 20 times larger than the sun, and if you stretch out your arms and compare to your orange, you have the relative scale of an O-star to the sun.

On this scale, the entire Earth is roughly one milllimetre across: the thickness of your finger nail.

Huge

You might already be impressed with the sizes of stars, but we have barely begun. Once a star has exhausted the hydrogen fuel in its core, new phases of nuclear burning begin and these radically change the make up of the star.

For the sun this means that, in roughly 5 billion years, it will begin to swell, and its surface layers cool, and it will grow into a monster star – a red giant – with a radius around 250 times its current size.

This future sun will engulf the orbits of all the inner planets, including that of Earth.

To get an idea of this scale, take your orange – which still represents the sun – to a cricket ground, and place it in the middle of the pitch. On this scale, the surface of the red giant would touch the wickets, 20 metres apart.

And remember, the thickness of your finger nail still represents Earth.

Supergiants

For stars more massive than the sun, their evolution into giants is more extreme: they become supergiants and Hyper-Giants, which, while rare, are the largest and most luminous stars we know.

They represent a tumultuous stage of stellar evolution, with many pulsing and beating as the outflow of radiation struggles to battle the inward squeeze of gravity.

For the most massive stars, when gravity eventually wins, they collapse and explode as supernova, spewing constituents into the inter-stellar medium and seeding the next generation of stars.

One of the nearest red supergiants is plainly visible in the shoulder of the constellation of Orion.

Betelgeuse has a fiery red colour and a radius more than a thousand times that of the sun.

If our orange represents the sun, Betelgeuse would be 100 metres across, and when we place our sun at the centre of a rugby field, Betelgeuse would be touching the try-lines.

While this is spectacular enough, Betelgeuse is only half the size of VY Canis Majoris, the largest star we know.

If you visit Queensland, take your orange to the observational deck of Q1, the tallest residential building in Surfers Paradise. Hold your orange by the window.

VY Canis Majoris would reach from the ground to your 230-metre-high vantage point. Your orange would certainly appear pretty inconsequential.

This star is truly immense, with a diameter of almost 2 billion kilometres. It appears to be highly unstable, suggesting it is close to stellar death, and it is expected that at some point in the next 10,000 years, VY Canis Majoris will explode as a spectacular supernova.

But here, at the size of the largest star, we must stop. There are many more scales of structure we could talk about in the universe, from dwarf galaxies to superclusters, but these can wait.

I’d like to finish on another question of scale, the distance between the stars.

As you sit with your orange in the middle of the rugby field, the nearest other star, Alpha Centauri, would be similarly orange-sized.

But this orange would be 2,300 kilometres away – the distance between Melbourne and Cairns – with virtually nothing in between.

Look again at the thickness of your finger nail, representing our planet and all of humanity, art, science and literature, all the people who have ever lived, and think about our place on the cosmic scale.

It’s quite a sobering thought.