There will be no Big Day Out in 2015. It’s been confirmed by American owners of the Aussie event, C3 Presents.

No more, the clusters of very bright-eyed, over-stimulated teens drifting from stage to stage, throwing their arms up in the air to bands they had likely never even heard of, except for that one song. You know the one.

No more, the heaving sea of half-dressed, over-Lynxed bodies, covered with tedious tattoos and a thin film of sweat laced with someone else’s vomit. No more. Facebook is alight with nostalgic yearning.

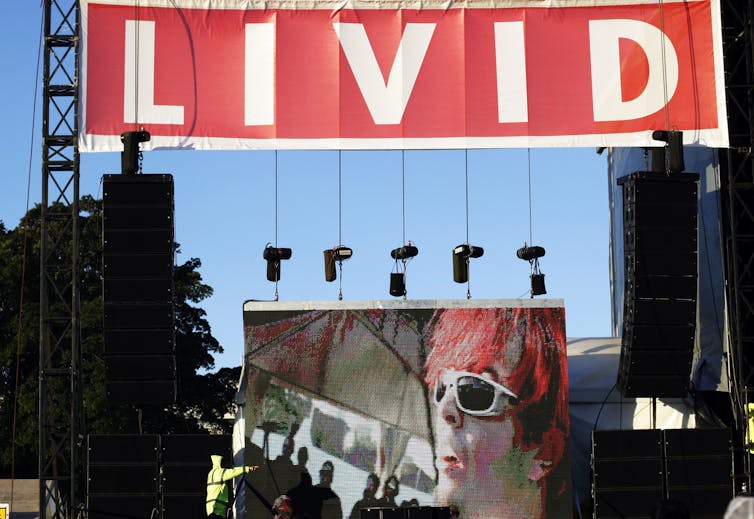

Brisbane indie rock band The Go-Betweens, with yours truly playing bass, headlined the first Livid festival in Brisbane in 1989. It was a hot January evening, with 1,800 punters in a tent at Queensland University.

This was the beginning of it all, really.

The organisers drove home with a boot full of cash. Although there had been big outdoor rock music festivals in Australia since the 1970s, Livid started the inner-city outdoor festival trend that swept into this century. Livid expanded through the 90s and has not been held since 2003. It was a lesson in how to run a great festival. But the market started to heat up.

The Big Day Out (BDO) music festival started small in Sydney in 1992, and Homebake (all Australian acts) started in Byron Bay in 1996. History tells us that this is how successful festivals happen. They grow into the mainstream from humble, if ambitious, beginnings.

Over the last 20 years there have been a number of attempts to swagger in fully formed, with massive lineups and corporate backing. Some of these have been less than successful: Alternative Nation, in 1995, was a vehicle for the promoters Michael Chugg and Gudinski, and radio station Triple M, to grab some of those tasty festival dollars, but it fared poorly and never made it to a second date.

Michael Coppel’s V Festival, a spin off the British V Festival sponsored by Virgin mobile, had a fractured life, an ungainly structure of sideshows and ticket price issues - it lasted for 3 years.

There were plenty more short-lived festivals.

These incursions only helped to increase competition for what was a limited pool of bands, and artificially inflate prices of both bands and tickets for the big festivals. It also had adverse effects on the second-tier festivals, who were priced out of the market and struggled to survive.

But greed plays a significant role here, and the large rock festivals got bigger. They needed massive audience numbers to break even – 200,000 festival-goers for BDO, according to one industry source I spoke to last night.

The diversity that big festivals used to employ as a calling card dissipated as genre artists were syphoned off to genre festivals: EDM, heavy metal/hardcore. These days a punter has bloated, blander lineups and higher ticket prices. It’s no wonder they’ve stopped going!

It is also accepted in the industry that this is a cyclic trend, and the turnaround will happen, but it will take another seven years or so. But there are some very obvious exceptions to this complex set of circumstances that has stalled the Big Day Out.

Genre-based festivals are doing very well indeed. Soundwave, a national punk/metal/rock festival has drawn the metal heads away and has been running for seven years.

National dance music festivals such as Stereosonic have big overseas investment and don’t look like slowing down. Woodford Folk Festival started in 1987, with some lean years recently, but nearly 120,000 people came through the gate last New Year’s Eve while Byron Bay Bluesfest gets 30,000 people a day through their dazzling lineup of acts.

Add to these the small festivals offering boutique experiences, like the Falls Festival, Meredith Festival and travelling regional festival Groovin’ The Moo. And of course, the growing popularity of the extremely urban Laneway Festival which has spread from Melbourne since 2004 and presents the newest of new music.

The elements that seem to unite these survivors are heartening: a passionate regard for the music they want to present; a respect for the people who want to come and share that music; and a commitment to the idea of the “experience” - the notion that promoter, artist and punter are all getting something out of this.

It is a shared love of one of life’s mysteries: the power of authentic music. Music that touches the heart and opens the mind.

And once the mind is free, well, the ass will follow! So says Funkadelic’s band leader George Clinton.