In a recent, widely reported recording of Pussy Riot protestors being arrested at the World Cup final, a voice can be heard saying, “sometimes I regret it isn’t 1937”.

In 1937, Stalin’s terror was at its height – and the secret police operated with impunity against political opponents. The Pussy Riot members were handed 15 days in prison. For around 70 Ukrainian political prisoners currently incarcerated in Russia, however, it feels like that individual’s nostalgic wish has already come true.

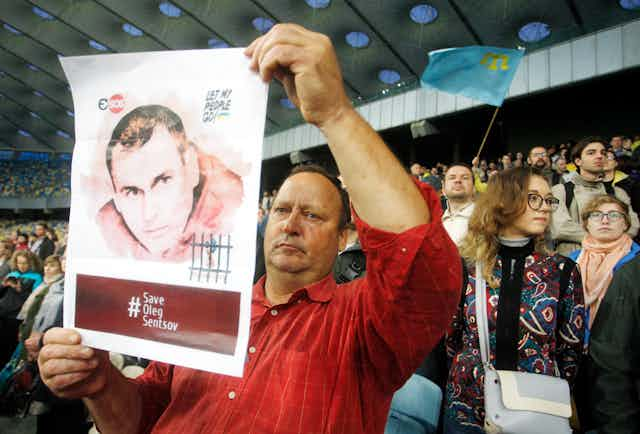

The best known of those prisoners is the Crimean filmmaker Oleg Sentsov. When the Euromaidan protests broke out in 2013-14, Sentsov paused work on his latest film and threw himself into the movement. By the time Russia invaded Crimea, he was a vocal and active opponent.

He and three other activists – Oleksandr Kolchenko, Hennadiy Afanasiev and Oleksiy Chyrniy – were arrested by the FSB, Russia’s secret services, in May 2014. He was later sentenced to 20 years in prison. On May 14 this year, Sentsov declared an unlimited hunger strike. His only condition for stopping the strike is the release of all Ukrainian political prisoners in Russia. According to his lawyer, Dmitry Dinze, who visited the director on July 19, Sentsov’s health has suffered considerably and he has been having problems with his heart. Nevertheless, he still refuses to accept any food and has managed to avoid being sent to hospital for force feeding.

Sentsov’s case condenses all that is wrong with contemporary Russia: its contempt for the rule of law, its predilection for violence, its propensity to lie and its lack of respect for the sovereignty of neighbouring states. The case also makes 1937 seem much closer than the overheard World Cup final comment might suggest.

In the 1930s, leading Ukrainian figures who insisted on cultural and political autonomy for Ukraine were arrested, tortured and forced to confess to membership of anti-Soviet, nationalist terrorist groups. Hundreds of writers and artists were executed.

Sentsov and his co-accused have claimed that they were tortured in an attempt to extract confessions. The FSB accuses them of being members of a Ukrainian nationalist organisation banned in Russia and of planning acts of terrorism, including setting fire to an office of Putin’s United Russia party and attacks on Soviet monuments.

Sham trial

Another striking parallel with the 1930s is that the state does not hide the fact that Sentsov’s trial is a grotesque parody of justice. On the contrary, just like the show trials of the 1930s, the spectacle is designed to demonstrate the regime’s unlimited ability to punish. To paraphrase an old Soviet saying, “If we can find a suspect, we can find a crime.”

The absurdity of the trial is made clear in a film by the Russian director Askold Kurov, The Trial: The Russian State vs Oleg Sentsov. Kurov employs minimal commentary: it is enough to simply show the court proceedings for the flimsiness of the accusations to be made clear.

One of Sentsov’s co-accused, Afanasiev, was initially a key witness against the director but later retracted his statements, which he claimed were given under duress. The court continued to use his evidence. Claims of the group’s far-right ideology were also highly questionable. Not only does Oleksandr Kolchenko have a history of left-wing activism, but one piece of evidence used to incriminate Sentsov was a DVD found at his home of the Soviet director Mikhail Romm’s film Ordinary Fascism – a famous anti-fascist film.

Details of material evidence in the trial was not shared with journalists or the public, and the lawyers were made to sign an agreement not to reveal details. Dinze claimed that other than the dubious testimonies of Afanasiev and Chyrniy (who also later stopped cooperating with the investigation), he had seen absolutely no evidence of Sentsov’s guilt.

Watching Sentsov in the dock in Kurov’s film is both troubling and inspiring. He is disconcertingly calm. He smiles bemusedly, gives the peace sign to the cameras. At one point he grins as his lawyer shows him, through the bars of his cage, a recently published collection of his short stories.

Sentsov’s words to the court were eloquent and cutting. In a statement in July 2014, he exposed the neo-imperial arrogance of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. “I am not a serf,” he told the court. “I cannot be transferred with the land. I did not submit any request for Russian citizenship, nor have I renounced my Ukrainian citizenship.”

This statement referred also to the two million Crimeans who had no say in the incorporation of their home into the Russian Federation, other than in a sham referendum, the legislation for which was passed in a Crimean parliament occupied by Russian soldiers.

For Sentsov, Russian society is facing grave challenges to freedom of speech and conscience. While many in Russia are taken in by the state’s propaganda, Sentsov states, there are others who are simply afraid:

They think that nothing can be changed. That everything will continue as it is. That the system cannot be broken. That they are alone. That there are few of us. That we will all be thrown into prison. That they will kill us, destroy us. And they sit quietly, as mice in their holes.

Observers in the West, in contrast to Russian citizens, have no excuses for not knowing or not speaking about what is happening in Russia. They have access to all the information and nobody will punish them for how they react to it. Judging by the Western media over the period of the World Cup, however, our societies have chosen to react by enjoying the football and ignoring the violence and abuses. Human rights organisations, a string of famous directors and some Western governments have called for Sentsov’s release, but these appeals have been lost in the football fever. Dozens more Ukrainian prisoners are entirely unknown in the West.

This speaks to another striking parallel with Soviet times: as Kateryna Botanova recently noted, Soviet hunger strikers in the 1980s were often struck by the indifference shown to their protests. “We simply didn’t exist,” said the dissident Anatolii Marchenko, who died after staging a hunger strike in 1986.

This silent indifference is not the same as the silent cowardice resulting from fear that Sentsov spoke about in his courtroom cage. It’s a problem he doesn’t have the luxury of having to confront.