The Senate Community Affairs Committee has announced its intention to consider the involuntary or coerced sterilisation of people with disabilities in Australia. Unless it focuses on the right of people with disability to live free from discrimination, the history of inaction on the issue is bound to continue.

Even though the issue of forced sterilisation has received policy attention since the late 1980s, we have surprisingly little information about the extent of the practice. A 1997 report showed permission was given by the Family Court and other state-based guardianship tribunals for 17 procedures to be carried in the period from 1992 to 1997, but Health Insurance Commission statistics showed that 1045 sterilisations were carried out in that period.

A report tabled in the Senate in 2000 disputed these figures and a 2001 report from the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission demonstrated the unreliability of data in this field while lamenting that the debate was reduced to numbers and not concern about girls and young women with intellectual disability.

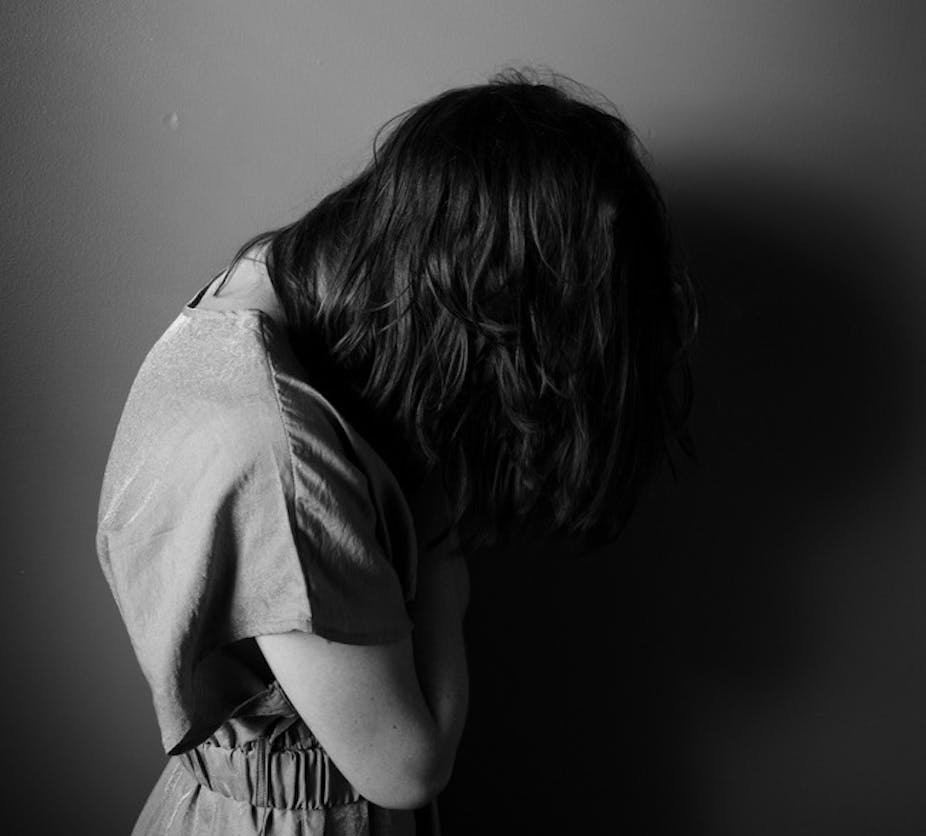

What we can be confident about is this – forced sterilisation is exclusively directed at girls and women; boys and young men do not figure in the discussion. And there are no recorded instances of the procedure being sought for non-therapeutic reasons for girls or young women who are not disabled.

A turbulent history

Non-voluntary hysterectomy was widespread in Australian disability services until the 1980s. Generally, parents, doctors and service providers arranged the procedure for prepubescent girls about to enter group home accommodation. In fact, girls and women had to be shown to have been sterilised before they could enter such accommodation. Whether those who remained at home were also forcibly sterilised is not known.

In the United States, forced sterilisation was compulsory for disabled girls even when they were living in their home community, although blanket sterilisation has been challenged there since the 1980s. Stephen Jay Gould’s 1985 essay “Carrie Buck’s Daughter” explored this practice as a type of eugenics policy. Opponents of the practice in Australia also identify the assumptions behind forced sterilisation of disabled girls as being based on eugenics.

Australia’s approach of forcibly sterilising most intellectually disabled girls was challenged in the Family Court in the 1990s. A 1992 appeal to the High Court clarified the question of who should decide whether a disabled girl should be sterilised. All decisions from that time must be made in the Family Court or an acceptable state-based tribunal and then only if there’s compelling evidence that it’s in the girl’s best interest.

During the first part of 2000s (based on evidence of “irregular” procedures), the Australian Standing Committee of Attorneys-General (SCAG) Working Group sought agreement from all state governments to a Sterilisation Model Bill. The aim of the Bill was to provide a nationally consistent approach to this issue, but it was withdrawn in 2007 due to lack of agreement from the states.

In 2010, the federal attorney general told the United Nations that very few such procedures were being carried out. No data was offered to support this conclusion.

Disability advocates suspect that girls are now taken overseas or that euphemisms, such as menstrual regulation, are used to refer to forced sterilisation and that it is still performed on disabled girls in Australia.

Dubious justifications

Proponents of forcible sterilisation fear disabled girls’ reaction to menstrual blood, be it disgust or fascination – and that their personal hygiene will suffer.

And as they grow older, girls face a different rationale. At this point, the focus swings to sexual activity or abuse, and contraception. Australian women with disability are at higher risk of sexual exploitation and abuse than the wider female population. And proponents argue sterilisation is necessary to ensure disabled women don’t conceive as a result of sexual assault.

Apart from the clearly heartless justification of this position – we can’t keep you safe, so we will stop you from becoming pregnant – opponents see this as exposing disabled women to further risk by effectively offering protection to perpetrators of sexual assault.

Anecdotal evidence from workers in the child protection field suggests that women with intellectual or psycho-social disabilities also face strong pressure to be sterilised if they have children in child protection. The threat of coercion for these women is obvious - they fear that they won’t be allowed see their children unless they acquiesce.

Doing the right thing

Over the past 20 years, various bodies have sought clarity about who should decide whether a disabled woman is sterilised with many, including Women with Disabilities Australia (WWDA), advocating a complete ban on sterilising girls without medical necessity.

South Australia and New South Wales have clarified guardianship laws for adults and the Family Law Council has detailed guidelines for decision-making in the Family Court following the 1992 High Court case mentioned above.

With this recent history, it’s tempting to conclude that the inquiry could make little difference. But ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability is driving significant policy changes as all Australian governments to come to grips with what it means to pursue a comprehensive rights framework.

Academics and advocates are calling for a national adult protection framework to address this issue along with other rights abuses reported in services. A commitment to such a rights framework will assist the inquiry heed the voices of women who will be affected by a national policy in this area.

Sterilisation for non-therapeutic purposes should never substitute for proper support with menstruation, sexual safety and support when disabled women become mothers. Without the dedicated pursuit of their right to bodily integrity, competing interests will have their sway and disabled girls and women will continue to face forced sterilisation.