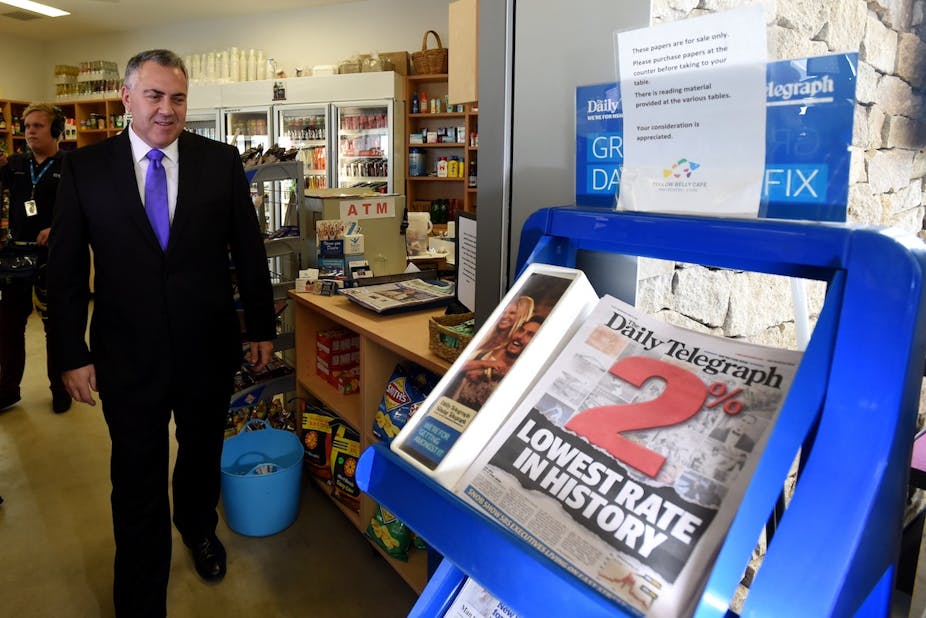

The decision of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to lower the cash rate to 2% this month is good economics.

The output gap (i.e. the difference between actual GDP and its trend level) is negative and widening, and inflationary pressures are very subdued, so the interest rate can be reduced to stimulate production and employment.

With its decision, the RBA has sent two signals. First: the ongoing economic contraction is serious and needs to be taken care of. Second: monetary policy is ready to play its part to support the recovery.

To whom are these signals addressed? Certainly to consumers and the business community, whose falling confidence will be somewhat restored by knowing the RBA is not going to repeat the mistakes of its European counterpart.

But primarily, these are signals that the federal government ought to pick up, and act upon, otherwise Australia will experience the recession we managed to avoid in 2008-09.

This means that, consistent with the RBA’s expansionary monetary policy, the federal budget should include expansionary fiscal measures to support aggregate demand.

If instead restrictionary measures aimed at reducing debt become predominant, then Australia’s economic barometer will take a turn for the worse.

The cruellest month

April was a month of bad economic news for Australia.

On April 15, the World Economic Outlook (WEO) of the International Monetary Fund presented projections for the Australian economy that were significantly worse than those reported only six months before.

Most notably, the October 2014 issues of the WEO estimated the output gap in 2014 would be only -0.095% of trend GDP. But in the April 2015 issue, the output gap has been revised to -1.4%, with projections that it will remain negative in 2015-16.

This indicates the contraction is deeper than expected. The slow growth of gross domestic income throughout 2014 confirms the underlying weakness of the Australian economy.

On April 23, the NAB Quarterly Business Survey saw a drop back in business confidence in the first quarter of 2015, coupled with softer business conditions and moderately worsening expectations for future activity.

Some more comforting news came from the ANZ/Roy Morgan Poll, which showed stable, if not moderately increasing, consumer confidence throughout April.

But unfortunately, this trend was short-lived and as of the first week of May, consumer confidence had fallen to the lows it experienced at the beginning of the year.

To complete this rather gloomy picture, seasonally adjusted labour data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics saw the number of employed persons in the country decline by almost 3% in April. The number of unemployed persons increased by 7%, and the unemployment rate grew from 6.1% to 6.2%.

All this bad news is obviously linked. Worsening economic projections hurt confidence and lower confidence results in slower economic activity.

Breaking this potentially vicious circle will require an adequate mix of macroeconomic policies.

Look on the demand side

By cutting the interest rate twice in the first four months of the year, the RBA has made it clear the recovery is a matter of sustaining aggregate demand through expansionary policies.

But we cannot expect monetary policy alone to bring the Australian economy back into good shape. When the interest rate is already low, further interest rate cuts are likely to produce only moderate expansionary effects.

Fiscal policy therefore needs to play a prominent role, which in today’s circumstances means the government ought to provide some fiscal stimulus via the budget. In simple terms, the stimulus should consist of more public expenditure and lower taxes.

The data show that one dollar spent by the federal government increases Australian GDP by 1.2 dollars. Therefore, by increasing expenditure the government can effectively help the recovery.

Conversely, if the government was to reduce expenditure and/or increase taxes, then it would nullify the action of the RBA and cause further uncertainty and loss of confidence.

Moreover, despite what some might believe, a fiscal stimulus today does not mean compromising the future debt position of Australia.

For one thing, the debt to GDP ratio in Australia is still low by international standards. And the fiscal stimulus should only be temporary, reversed as soon as the economy turns around.

This cyclical patter of fiscal policy will guarantee that deficit is not systematically accumulated over the medium to long term and as a result, that the debt level remains sustainable.

The economic policy debate in recent years has essentially focused on the debt issue, with some very strong rhetoric suggesting Australia has a debt problem. Consequently, deficit reduction and debt stabilisation have become the primary concerns of fiscal policy.

But what is costing the Australian economy jobs today is the economic contraction, not debt. Households’ welfare and business profits are under threat because of the contraction, not because of debt. Similarly, the economic prospects of the youth are worsening because of the contraction, not because of debt.

The real problem for Australia is to get out of the contraction, not to lower debt. It is now up to the government to formulate a budget that rises to this challenge.