The recent case of “cheating” at Volkswagen is still reverberating around the globe and threatens to reveal similar antics in other corporations.

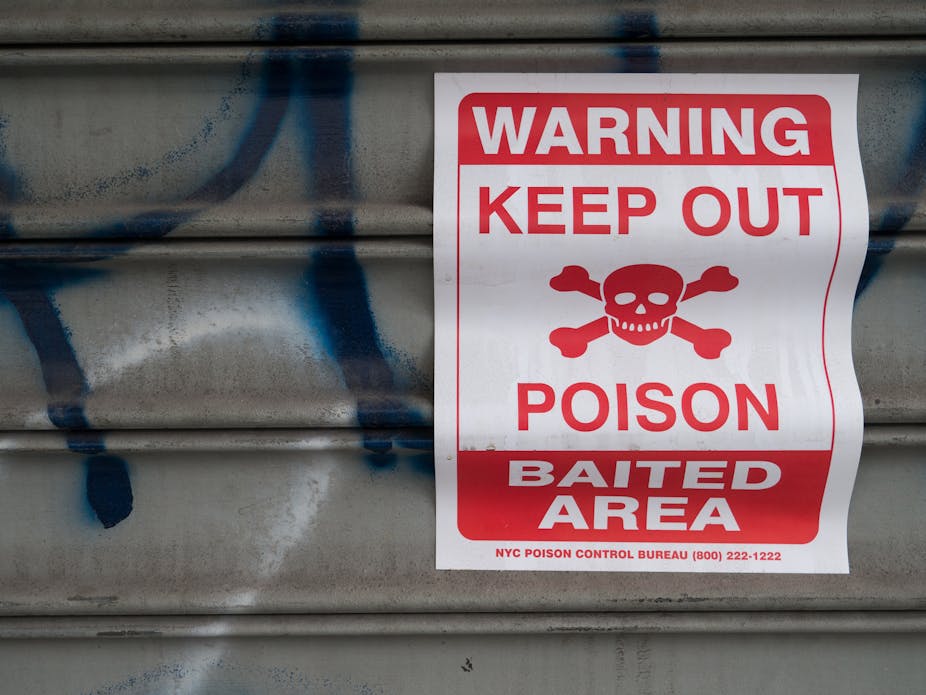

Innovation takes new ideas and creatively applies them in the real world in ways which create value. But what if value is created for some in the short term but the impact for others is negative? The VW story points towards innovation that is toxic – either to customers, the offending organisation itself, or in the end, to both.

Toxic innovation develops and changes products, services or backroom business processes that harm customers. It can be deliberate and born of greed; it can be the result of benign but misguided intent; it can be an utterly unforseen and indirect effect. Ultimately, it can damage or destroy the organisation behind it.

Clumsy companies

The VW case is just one among other innovation stories where the same skills that produce genuinely successful products are put to the service of narrow financial goals that result in damaging impacts. Not all of these impacts are deliberate or conscious or known in advance.

This phenomenon is often based on an endemic troubled business culture. When banks were recently outed for rigging the LIBOR interbank lending rate, this kind of rotten culture was uncovered as well. The LIBOR rigging process itself was remarkably innovative and involved plenty of creative activity. It was also illegal and its impact on banks and the world economy is still felt today.

VW’s environmental “cheat” – deploying software that could trick emissions tests – allowed the car to pollute and no one to be any the wiser. It appears VW was warned not to do this, but the extent to which this deception was known in the higher echelons of the company is yet to be discovered.

So a potentially innovative bit of in-car software became toxic – for the environment in terms of emissions and ultimately in terms of poisoning the Volkswagen brand. What the case has also thrown up is that it is the emissions tests themselves that would benefit from some real (and non-toxic) innovation.

Designed to fail

Another example can be found in the concept of “planned obsolescence”. Part of all good innovation involves testing products and knowing in advance how and when they will begin to, and ultimately totally fail. That’s vital for safety, for maintenance and product replacement. So, when companies began to be accused of knowingly engineering products to fail or deliberately making them harder to repair, then it doesn’t feel like their ingenuity is devoted to us lowly consumers.

We saw the impact of this idea recently when a Harvard study raised questions over whether an operating system update by Apple was slowing down iPhones at a time when product upgrades became available. Now, new software often loads new features which in turn demand more resources and can cause systems to slow, in fact it is a major part of the technology sector’s appeal that companies are constantly seeking to attract customers towards enhanced products. Customers who felt the iOS9 update was slowing down their older phone may have been wrong, but the suspicion alone can be enough to damage trust in a brand.

There is certainly growing evidence that consumer electronics firms are focusing their innovation efforts on making it harder to repair products. If it ever does emerge that clever design by smartphone manufacturers is used to hobble older phones and bully us by stealth us into upgrading, the scandal could at least partly match that which has befallen VW.

Innovation or intrusion?

Facebook saw 4% wiped off its share price when its platform went down for several hours (and not for the first time). One reason cited for this was engineers engaging in incremental, small-scale innovation which crashed the whole network. This was unintended but the result was a lot of damage to Facebook’s reputation as an always-on social media platform.

Perhaps more significantly, its attempts to change a core part of its platform, the “timeline”, and introduce a supposed innovation known as the Year in Review, resulted in significant negative impact on its brand. Users started seeing photos they would rather have forgotten suddenly appearing under their noses. A phrase – “inadvertent algorithimic cruelty” – was even coined to describe this, and the firm was forced to issue an apology.

Not so Sunny Delight

Facebook’s clunky attempt to spice up its offering might have been a failure of technology, but perhaps the most damaging innovations happen in marketing.

Kids’ drink Sunny Delight was marketed to parents as a healthy fresh orange juice product. It turned into a brand disaster when parents discovered it was actually artificially coloured sugar water – and sales crashed.

The back room designers of this product had engaged in all kinds of product innovation activity to fool consumers into believing this drink was healthy and full of orange juice goodness. From pictures of oranges on the bright and optimistic packaging, to colour and taste – what we really had was a cheat product.

In short, VW is only the most current and most prominent example of toxic innovation. If corporations want to keep the trust of their consumers they will have to design toxic innovation out of their broader innovation activity. Sadly, stories are emerging in increasing frequency in which companies are applying the same skills they use to brings us wonderful products and services, to cheating, deceiving or in simply trying to be clumsily smart. The result is damage for everyone along the supply chain.

As the Volkswagen case shows, these attempts – or at least the ones we find out about – are a massively false economy. Innovation is always more successful in the long run when it is conscious, connected to real customer benefit, and generates trust and confidence.