We hear many tales about bees and honey. Even economists may base their theories on fantasy hives. Dieticians can do the same when promoting the imaginary health benefits of honey, and then there’s the honey itself. It should be one of the purest products of nature, yet what we find on supermarket shelves can be cut with syrup, tainted by antibiotics, or sourced from China despite a label that claims otherwise.

So let’s take a worldwide tour of the honey trade, which oscillates between truth and tall tales, with a few tips for your coming purchases.

Bee theory

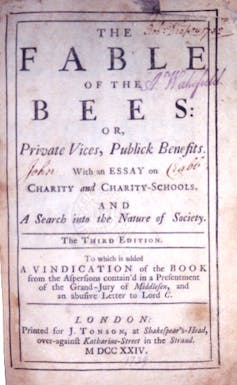

The social life of bees has long fired up our imagination. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) admired their political organisation, with its chiefs and councils. He even thought that moral principles guided their behaviour. Nearly 1,700 years later, the Anglo-Dutch author Bernard Mandeville took the opposite view, describing a vice-ridden hive inhabited by selfish bees. The Fable of Bees, published in 1714, became a work of reference for political economists. A precursor to Adam Smith, whose invisible hand of individual self-interest fed the common good, Mandeville set out to prove that, unlike altruism, selfishness was productive. Hostile to frugality – wealth stolen from a miser will trickle down, after all – he inspired Keynes’ critique of excess saving.

In fairness to Pliny, Mandeville and many others who have fantasised about bees, the hive as we now know it, with its removable wooden frames, had yet to be invented. So it was difficult to observe the life and social mores of bees. There were no glass walls enabling us to watch their busy work or count drones, males whose only purpose in life is to mate with a virgin queen. Nor were there electronic tags to monitor the ceaseless movement of bees and discover that to produce a pound of honey they must cover a distance equivalent to flying around the world, visiting some 5 million flowers on the way.

James Meade, a British economist who was awarded the 1977 Nobel prize for his work on international economic policy, had no such excuse. In the early 1950s he cited the example of apple-growing and beekeeping in the same area to illustrate his theoretical analysis of external economies. Each serves the other: the bees gather nectar from the apple blossom to make honey and in so doing pollinate the flowers which in turn become fruit.

Meade theorised that because these reciprocal services are unpaid, both parties under-invest: Beekeepers set up fewer hives than is economically optimal, because they take no share in the marginal product apple growers obtain from a bigger harvest. Orchard owners plant fewer trees than is economically optimal, taking no share in the marginal product beekeepers derive from extra honey. This example was a big success with economics professors and their students, no doubt on account of its bucolic character and springtime atmosphere.

Unfortunately, Meade was mistaken on two points. First, he did not know that apple blossom contains very little nectar, which is perhaps excusable. Apple-blossom honey, should you find some in a shop, is actually made from the flowers of other plants in the orchard. Second – and this is a real blunder – he overlooked the many arrangements between growers and keepers for their mutual benefit and reward. So there was in fact no sign of free, unpaid production factors, and hence no external economies. Steven Cheung, a specialist in property rights and transaction costs, made this point with a survey of beekeepers and tree-growers, whose deals abide by rules rooted in tradition or are actually framed in full-blown contracts.

Bees sometimes travel by truck

American beekeepers have been charging for their pollination services for years. But the almond boom has massively increased the scale of these operations. Every year millions of hives are trucked to California’s almond orchards from other parts of the country. Accounting for almost 80% of global demand, the farms play host to some 30 billion bees for a few weeks. The hives are then taken to Florida or Texas to pollinate other trees.

Bees and beehives travel around other countries, too. In France, they move from one region to another to gather pollen from flowering plants and trees at their best. At different points in the season the same hive may produce honey flavoured by Mediterranean garrigue (scrubland), acacia trees and finally lavender bushes. Unlike their US counterparts, professional beekeepers in Europe countries earn their living from producing honey, and not mainly from pollination services. Nor is there much trade in bees here.

Until recently, the transportation of bees in China was largely for honey production, not pollination. But in provinces such as Sichuan, the balance of earnings is shifting toward pollination. This is indirectly due to a local shortage of bees coupled with an increase in the land given over to orchards. But the root cause is the massive use of pesticides on apple and pear trees. Having lost their bee colonies, beekeepers are reluctant to truck their hives to such places.

Trade in honey has far greater global reach than any commerce in bees themselves. In Paris, Berlin or London shops – specialist outlets or high-class grocers – you can find honey from as far afield as New Zealand or Cuba. Retailers also sell Chinese honey – but often unknowingly. In Europe, if a honey’s label indicates a “blend of non-European Community honeys” or “blend of EC and non-EC honeys” this is very likely the case. China is the main source of honey imported to the EU, followed by Ukraine. (This may change, as new EU labelling rules require each source country and its share be indicated.)

Fraud far afield

As in many other domains, China is the world’s leading producer and exporter of honey. But such statistics should be taken with a pinch of salt, as it were. The most common way of adulterating honey is to add sugar syrup, which is much cheaper and not easily detected. Either jars are simply not checked – inspection during the production process or on importation is exceptional – or it just goes undetected. Some types of sugar can only be spotted using expensive technology such as nuclear magnetic resonance.

A 2016 article in the American Bee Journal, “A Study of the Causes of Falling Honey Prices in the International Market”, makes a compelling case that only adulteration with sugar can explain the recent growth in exports by China, India and even Ukraine. In these countries – as indeed elsewhere – domestic demand has not dropped (which would have released volume for the export market). Nor has hive productivity increased (on the contrary, bees are plagued with increasingly acute health and environmental problems). Lastly, the number of hives has only slightly increased because of the lack of attractive profit margins and extensive training of new beekeepers.

Another form of fraud involves “laundering” honey by concealing its true origin. Countries such as Vietnam and Thailand export more honey than they could realistically produce. The difference is made up with Chinese exports, and the resulting blend is shipped to the United States. China has been targeted by an anti-dumping duty since the early 2000s, but labelling it as coming from the stop-over country gets around that obstacle. Other circumvention schemes include fake shipper bonds and under-evaluation of entries. It is estimated that in 2015 about one-third of the US honey supply came from China.

A third type of malpractice hinges on non-compliance with health and safety regulations. Honey may contain pesticides or antibiotics that are either prohibited or exceed limits. Hives can be treated with antibiotics (to combat American foulbrood, a disease caused by a spore-borne bacteria), but the drugs may also accumulate in their surroundings. The idea of unwittingly consuming antibiotics along with one’s honey is particularly shocking given that it naturally contains defensins, small proteins that help to kill microbes.

The presence of pesticides in honey results from beekeepers treating their hives or similar products used in farming. Whatever the source, most honey contains a few micro- or nano-grams of such chemicals. Japan has recently warned it will stop importing New Zealand honey because it detected glyphosate, a weed killer used in kiwifruit orchards. While the pesticide residues sometimes found in honey are not a risk for our health, some substances, in particular neo-nicotinoids, are deadly for bees. Experimental evidence shows that while neo-nicotinoids don’t kill bees outright, they can cause them to become disoriented and prevent them from finding their way back to the hive. In general, pesticides contribute, to a degree as yet difficult to determine precisely, to colony collapse disorder. Many factors play a part in this phenomenon, which has wreaked havoc in bee colonies around the world over the past 20 years.

Much as with other types of fraud, trade is distorted because producers and regions marketing substandard goods are passing them off as decent honey. Adulterated produce costs less, so producers and regions offering high-quality goods must compete at prices that deny them adequate margins and reduce their market share. Consumers also lose out. The medicinal and nutritional value of honey is lost when adulterated with corn or cane sugar, or soiled with chemicals.

Home is where the honey is

You may have gathered by now that I do not recommend buying Chinese honey. This is not to say that there is no good quality produce there, but we would need to know where to find it. The same goes for budget spreadable honey, as its true source is open to speculation.

At the top end of the price range there is New Zealand’s sought-after Manuka honey. This is a monofloral honey (predominantly from the nectar of one plant species) derived from the Manuka tree, native to southeast Australia and New Zealand. It boasts exceptional antiseptic and antibacterial properties. Due to the honey’s high price, New Zealand is second only to China for the value (as opposed to volume) of its honey exports. But retailing at almost 100 euros a kilogram, the precious honey attracts swarms of smugglers – five times more of (purportedly) Manuka honey is sold worldwide than is actually produced in New Zealand. As a general rule, if you want to buy premium goods from outside your country it’s wisest to go to a specialist retailer selling tested, selected produce.

For humbler, less exotic varieties, I would suggest honey sourced locally, which makes a difference in two ways. First, it corresponds to a particular ecosystem – specific plants and flowers as well as agricultural practices that have a significant impact on the flavour and contents of honey. Of course, if you live in an area with intensive farming and pesticide use, you have to be cautious. Do not hesitate to contact directly a local beekeeper and ask about their practices. That’s the second difference: getting direct information will tell you far more than a label that simply says English or French honey.

If you’re concerned about pesticide and antibiotic residues, you should opt for honey that is certified as organic. If you are concerned about the China contents in your “Born in the USA” honey, there’s a labelling program called the True Source Honey that can help you feel confident that the honey you purchase is the real thing.

François Lévêque is author of “Les Entreprises hyperpuissantes Géants et Titans, la fin du modèle global?”, Odile Jacob, April 2021.