After the 2015 general election, the UK will see a record number of women taking seats in the House of Commons. Yet the activity before and during election night has demonstrated that there are still significant obstacles to gender equality in our society. In fact, the biggest challenges that women face today aren’t always overt, political or structural – they’re often psychological.

The election coverage on Thursday night provided clear examples of the way women are portrayed in the media during important social events. While the first hour of the coverage revealed at least three women candidates had won their seats, the picture back at the studio was less than generous in its representation of women.

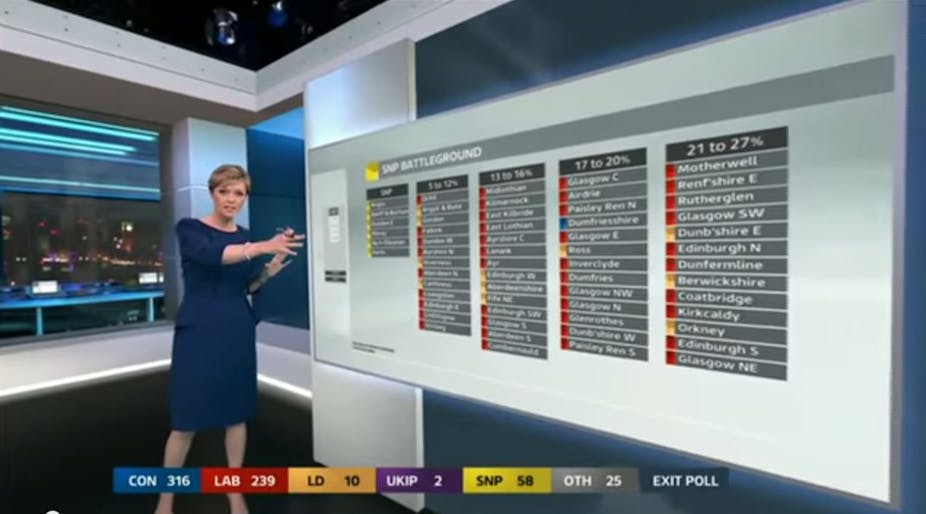

Almost across the board, commentary panels were populated by men in suits, providing what was proffered as expert and earnest insight. The role of number-crunching and visual description fell to the female members of the team in front of technical and dazzling display boards, harking back to the “barrel girl” sidekick roles of the seventies. When they weren’t working the tally board, women journalists were charged with less challenging roles, like roaming the set and chatting to experts from Facebook about the reactions on social media.

A swathe of Twitter commentary damned the under-representation of women in robust commentary roles.

Implicit bias

The way we see gender roles is formed and perpetuated by our interactions with our social environment. Our perceptions about these roles unconsciously influence how we value the contribution of individuals around us.

Recent work by Adrian Banks illustrates that human decision making is driven by what we’re comfortable with, and what we consider to be socially acceptable, due to regular exposure. In this context, women in certain roles may be unfamiliar. This means that when we’re appointing people to roles, the subconscious kicks in and defaults to a known position.

The media is used to putting men in suits on commentary panels, and the public is used to seeing women as “assistants”. It’s comfortable and familiar, and so no one on the production team gives a second thought to seeking out alternative panel members. Diversity of voice may not even have been consideration, because no no one consciously thought to question the lack of it.

On election night, most of what we saw delivered as intellectual and considered insight was conveyed by a male voice. This has an almost imperceptible but influential impact on how we generate our own ideas about gender roles, and the associated value of those roles.

Many structural and administrative barriers – such as overt discrimination – have been outlawed, giving women the opportunity to achieve in public and business life. But the psychological ones have not. In fact, invisible barriers – such as discriminatory opinions – may often rest with those who could provide avenues of achievement to women; employers, for example.

Much has been written about unconscious (or implicit) bias as an impediment to gender equality. Harvard Professor of Social Ethics, Mahzarin Banaji, who has spent many years investigating the matter, finds that most people reject the idea of overt discrimination. However, she suggests that while people may believe themselves to be perfectly open to diversity, this may not be reflected in their unconscious thoughts and behaviour.

Modern discrimination, Banaji suggests, is less about negative impacts on “them” – overt discrimination against women, for instance. Instead, it is more about the implicit behaviour and actions that favour those within the “in group” – for example, giving greater consideration and approval to the contribution of men.

Our unconscious biases are deeply embedded. They arise from what see around us from an early age. The media, of course, plays a highly influential role in constructing our version of what we consider normal.

Imposter!

What’s more, the “imposter phenomenon” suggests that a sense of “not being good enough” constrains some women, to the point where it actually limits their ability to achieve. Researchers Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes found that the imposter phenomenon is particularly prominent in high-achieving women, whose sense of anxiety about being “found out” as a fraud limits further achievement, due to motivation-crushing stress. In effect, successful women can unconsciously sabotage their own capacity to achieve even greater success.

Again, the social construction of what women know to be normal can inhibit their capacity to internalise and credit themselves with their achievement and instead, see their success as luck, a mistake or allowed as the token female offered favours to make up the numbers.

It is ironic, then, that while women candidates fared well in this election, it was still the responsibility of male-dominated commentary panels to explain that to us.

A productivity problem

The productivity crisis currently faced by Britain demands that all players make a greater, more efficient contribution to the workforce. This effort is hampered if a proportion of the workforce is working below capacity due to real but unconscious psychological barriers, which prevent them from reaching their full potential.

Despite decades of action to remove structural barriers to women’s participation in the workforce, recent ONS statistics show that only around 8% of women occupy managerial, directorial and senior official positions. In March, The Guardian reported that you’re twice as likely to find a man called David in the CEO’s role, than a woman. The seven female CEOs of FTSE 100 firms are outnumbered almost three to one by people with “Sir” in their title.

Statistics like these have been repeated time and time again, like a broken record playing over the past 30 years. We have anti-discrimination law and workplace policy that diminishes the risk of overt discrimination in the workplace. We have access to flexible working practices and return to work programmes for women after childbirth. Why is the tune not changing?

This is as much an economic issue as a gendered one. The underemployment, part time work and unrealised potential of women in the workforce constrains productivity and excludes many from making a full contribution, particularly in senior roles. And without visible role models in senior and “non-traditional” positions, the expectation that women won’t or can’t populate those roles is perpetuated.

These are some of the reasons we see men on our election panels, doing the hard thinking, while women look after the decoration and chat. These psychological barriers are underpinned by what we see in the media, and supported by social norms that take generations to shift. It’s ingrained, and it’s wrong. Until we see this sort of unconscious bias challenged and acted upon, we will never see our women fully able to achieve, and to make a full contribution to economic imperatives.