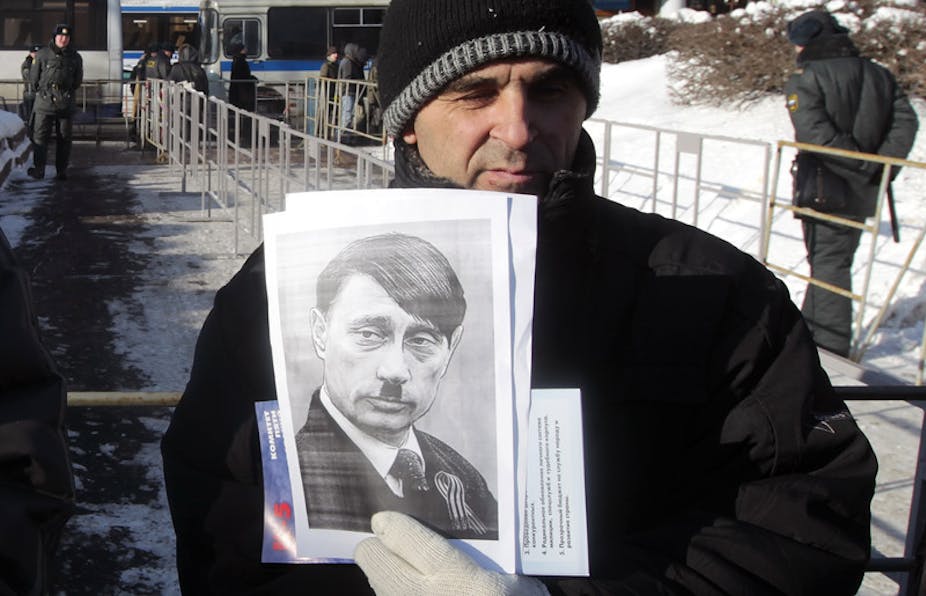

Since the very beginning of the Ukrainian crisis, many Western commentators have drawn comparisons between the present situation and pre-WWII Europe, as well as between Hitler and Putin. This has largely been part of a call for firm action against violations of international law by the Kremlin.

This kind of parallelism is not new; it is used every time there is a new enemy the public opinion should focus on. In recent years, according to Western rhetoric, Adolf Hitler has already been apparently reincarnated several times – as Saddam Hussein, Mohammad Qaddafi, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and more besides.

But while as a rule the direct comparison of any present statesman with Hitler is generally spurious, this time the broader context does in fact present some similar features. Specifically, Putin’s policy towards Crimea and Ukraine at large is gloomily echoing the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938-1939.

Obviously, there are important differences. In an earlier article, Professor Martin Brown has already pointed out that the annexation of the Sudetenland, the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia, did not take place by unilateral invasion nor by popular referendum, but as a result of a four-powers agreement that allowed Hitler to take it.

While significant, these differences do not outweigh the similarities between the two situations. In both cases, the nationality issue was a pretext for a territorial expansion of an aggressive and antidemocratic power. Hitler’s claim over the Sudetenland in 1938 was not utterly baseless; Czechoslovakia was a rather artificial offspring of the Versailles treaty, and had existed as an independent country only for twenty years. In the majority of the districts that joined Germany as a result of the Munich agreement, more than 50% of the population was indeed German.

Today, Putin can claim similar justifications for his actions in Ukraine. Crimea was the only district of Ukraine with a majority Russian population – nearly 60%. Historically, it was a Russian province; only in 1954 did the former Soviet President Nikita Khrushchev “offer” it to Ukraine – a rather meaningless gesture, since the two republics were at the time both part of the Soviet Union.

Aside from the local issue, in both cases the true problem was the violation of the global equilibrium. To this respect, 1930s statesmen proved much more naïve than their 21st century colleagues. At the time of the Munich agreement, the French prime minister Édouard Daladier privately admitted: “We cannot sacrifice ten million men in order to prevent three and a half million Sudetens from joining the Reich”. Similarly, Chamberlain wrote to Hitler: “I can’t believe you will take responsibility to start a European war for just a few days’ wait in the solution of this long-standing problem.”

They both completely missed the point, since Hitler’s objectives of course went far beyond reuniting all the German-speaking peoples under Berlin’s rule. And while historiography will never be able to state it as a truism, Germany was in all likelihood not yet ready for a global conflict, and Hitler might well have backed down if Britain and France had shown real firmness. Putting it bluntly, Chamberlain and Daladier were simply outwitted by Hitler.

Putin may not have such a grand design as the German dictator, but his plans are clearly not limited to Crimea. If any evidence of that was needed, the extent of the unrest in eastern Ukraine proves that Crimea was just a first step. The weakness of the new Kiev government may lead Putin to escalate more rapidly than Hitler, who waited a full six months before actually occupying Prague in March 1939.

Unlike Chamberlain and Daladier, today’s statesmen apparently understand the wider implications of Putin’s actions, and have shown firmness in condemning them. This has not made the dilemma they face any easier. How to prevent such deliberate aggression? How to avoid further violations of international law? United under the motto “act now, or regret it later”, the world’s great powers show little sign of agreement on a single course of action.

Other considerations make their task even more delicate. Many commentators have failed to note one fundamental difference between 1938 and 2014. In the last century’s case, Czechoslovakia was allied to France, and German aggression against it was therefore always likely to lead to a full-scale war; the Munich meeting was called at the very last moment to disguise Hitler’s guaranteed invasion as a legal occupation. An exact parallel today might be if Russia occupied the Estonian district of Ida-Viru, where 72% of the population is Russian.

Unlike Estonia, Ukraine is not part of NATO, so there is no legal obligation for any Western power to intervene in its defence unless such an intervention is sanctioned by the United Nations. In purely geopolitical terms, whereas Hitler’s action was one of a number of offensive moves he devised during the 1930s, Putin’s unwillingness to accept the new government in Kiev appears to be a rather more defensive move. From his point of view, the West was trying to set up a hostile government in what is still considered the Kremlin’s courtyard.

The central mistake of Munich was Neville Chamberlain’s apparent conviction that the scrap of paper signed by Hitler actually meant something.

Today, the Western dilemma is of a rather different nature: some people have argued that diplomatic and economic means are not enough to deter Putin over Ukraine, so Western diplomacy should include the threat of military action. Other commentators have described the crisis as heralding a new age of Western impotence, in which we can do little more than deny visas and flounce out of high-level summits.

This clash of opinions exposes a fundamental paradox of international relations in the nuclear era. Nowadays, the threat of military retaliation has lost credibility, and diplomatic arm wrestling can only rely on the threat of economic warfare. This can only be effective if a strong common front is built up internationally – but with so many private interests involved, that might be even more difficult to achieve than military action.

While the parallel with the history of appeasement should not be misused and applied uncritically, we should also pause before throwing it out entirely just because parallels with Hitler are a cliché. Similarly, it is important to avoid rolling the unique historical concept of appeasement into the general category of diplomacy – but also to avoid mixing up the need for a strong reaction with unrealistic and dangerous threats.