Boe Pahari’s short reign as boss of AMP’s lucrative investment management division and the resignations this week of AMP chairman David Murray and board member John Fraser have shown the power of major shareholders in public companies.

There was, you may recall, public outcry about Pahari’s elevation to chief executive of AMP Capital on July 1, after it was revealed he had been reprimanded for alleged sexual harassment in 2017 and docked 25% of his A$2 million bonus that year.

Read more: AMP doesn’t just have a women problem. It has an everyone problem

In any era – but certainly in the #metoo era – handing out a traffic ticket for (alleged) sexual harassment and three years later promoting the (alleged) wrongdoer to boss of AMP’s most important business was never going to fly.

In the end it was the company’s largest shareholder, Allan Gray Australia, that delivered Murray and AMP’s chief executive, Francesco De Ferrari, an ultimatum: go now or we’ll call a special general meeting to make it happen.

The only surprising thing in all of this is how AMP’s board could have been so stupid.

But it does raise some interesting broader issues. In particular, about the merits of the strategy Allan Gray used compared to a broader movement proposing “exit” or “divestment” of shares in companies that don’t act in accordance with investors’ wishes.

Exit versus voice

Throughout this saga, as far as we know, Allan Gray never threatened to sell its AMP shares. Rather, it told the board what it expected, and apparently got what it wanted – three heads on spikes. It made its voice be heard.

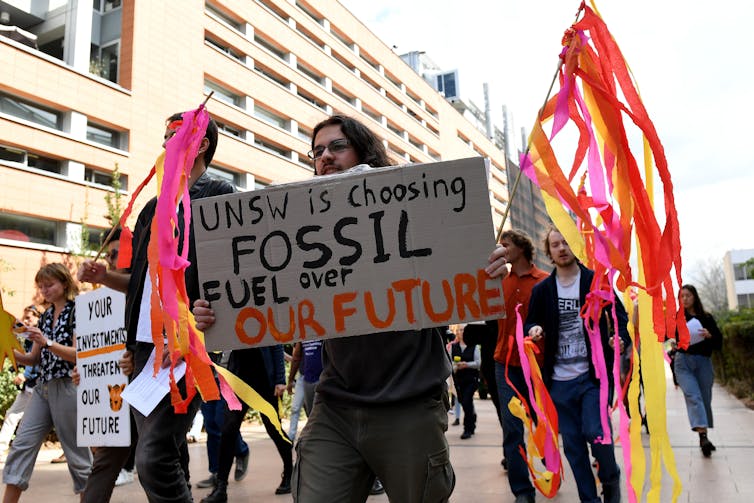

Compare this with threatening “divestiture” of shares. Divestment strategies have gained popularity in recent years, including a global movement pushing universities to divest from fossil fuel companies. Just this week three climate activists in pursuit of this goal gained seats on the Harvard Board of Overseers, responsible for its US$40 billion endowment.

Read more: Do the Maths: Bill McKibben argues for divestment

Divestment can be driven purely by ethical reasons – like the sustainability funds that avoid certain investments for environmental and social reasons – or it can come down to risk assessment.

This was highlighted by Larry Fink, head of BlackRock – the world’s largest fund manager with US$6.84 trillion in assets – in his annual January letter to the heads of major public companies.

Climate change, his letter said, had become “a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects”. BlackRock would stop investing in any company with “a high sustainability-related risk”.

Read more: Vital Signs: a 3-point plan to reach net-zero emissions by 2050

Which strategy is better?

So which of the two strategies – exit or voice – is better for an investor wanting a company to change its ways?

This question was taken up in a paper published this month by the US National Bureau of Economic Research.

In the paper, authors Eleonora Broccardo, Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales assume some investors and consumers are socially responsible, in the sense that they consider the well-being of others in making decisions. But other investors and consumers are purely selfish.

Their model applies to any type of business that can do harm, but the authors use environmental concerns as their working example. Consider a company that can choose to be clean or dirty. Suppose the environmental damage the dirty business produces could be avoided at a cost.

In this framework, divestment is meant to cause the market value of that company to fall, encouraging even “selfish” managers to invest in cleaner technology.

Selfishness and social responsibility

The problem, the authors note, is other players in the market weaken the effect.

The reason is that purely selfish agents will partially offset the effects of divestment/boycotting by increasing their investment/purchases in companies shunned by socially responsible agents.

The magnitude of that offsetting effect, the authors say, “is driven by agents’ risk tolerance for investors and by the utility of the good for consumers”. In other words, it depends on demand.

Furthermore the authors suggest, in line with evidence from experimental economics, unless the pollution is extremely harmful, it is not in the interests of any shareholders to actually exit.

So most shareholders won’t exit – or at least not enough to get companies to “behave”.

Getting to vote

What about the “voice” strategy? Here the authors consider a scenario where shareholders get to vote on whether a company should be clean or dirty.

Basic economics says an individual shareholder’s vote only matters if it is pivotal (i.e. it affects the outcome). In such cases a vote will be based on weighing the net social benefit from the clean technology, and the importance of others’ well-being, against their individual financial loss resulting from choosing the cleaner, costlier technology.

But here’s the key thing. If shareholders have diversified investments, a vote about one company will make a minor difference to their overall returns. So as long as the shareholder cares at all about the welfare of others, they will likely vote for the socially optimal goal – in this case, clean technology.

Corporate reforms

All of this suggests that making sure shareholders get to express their voice is important to achieving socially optimal goals.

That might involve more pro-shareholder measures, such as the opportunity to vote on issues the board traditionally decides (a kind of Athenian corporate democracy). Their ultimate power is voting out directors who don’t listen to them.

Read more: Social licence: the idea AMP should embrace now David Murray has left the building

There is a catch to this in practice, though. Most shareholders in Australia are represented by their superannuation funds, which don’t always do so.

This issue is known in economics as the “principal-agent problem” – something one of the authors of this paper, Oliver Hart, wrote about in a seminal 1983 paper co-authored with economist Sanford Grossman.

Perhaps the next step in our understanding of voting in corporate settings is to probe the limits of corporate democracy when shareholders’ interests are represented by fund managers who may not fully share those interests.