As COVID-19 sweeps across the globe, many politicians and news media have adopted war metaphors to describe the challenges we are facing.

In Britain, Queen Elizabeth II delivering a rare speech on Apr. 5 said “we will meet again” evoking a Second World War song. On March 9, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte also invoked the Second World War when he used Winston Churchill’s words to talk about Italy’s “darkest hour.” President Donald Trump has described himself as a “war-time president,” fighting against an invisible enemy.

In New York, as residents face the explosion of new cases and casualties, Governor Andrew Cuomo used the war metaphor extensively during a press conference:

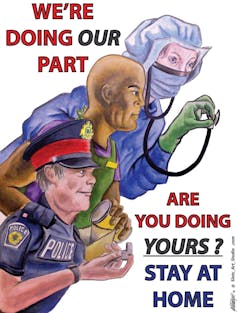

“The soldiers in this fight are our health care professionals. It’s the doctors, it’s the nurses, it’s the people who are working in the hospitals, it’s the aids. They are the soldiers who are fighting this battle for us.”

The United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Gutiérrez embraced the comparison during his remarks at a G20 virtual summit on the COVID-19 pandemic:

“We are at war with a virus – and not winning it. …This war needs a war-time plan to fight it.”

Journalists have also been using the metaphor. A recent headline in the Globe and Mail read: “We are at war with COVID-19. We need to fight it like a war.”

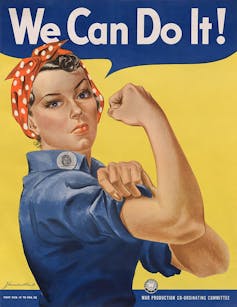

The war-time imagery is compelling. It identifies an enemy (the virus), a strategy (“flatten the curve,” but also “save the economy”), the front-line warriors (health-care personnel), the home-front (people isolating at home), the traitors and deserters (people breaking the social-distancing rules).

Furthermore, it highlights the urgency that underpins drastic policy decisions like the closing of schools, the imposition of travels bans, the grinding to a halt of economies around the world. It appeals to citizens’ sense of duty and obligation to serve in their country’s hour of need.

This is certainly not the first time leaders and policy-makers have used the war metaphor to describe a threat that does not qualify as military. Think the war on poverty, on cancer, on illegal immigration, not to mention the war on drugs or on crime.

While highly appealing as a tool of political rhetoric, the war metaphor hides several pitfalls that, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, are particularly dangerous.

Are we all soldiers now?

Using the war metaphor shuffles categorizations in insidious ways. For example, we are no longer citizens; we are now “soldiers” in a conflict. As such, politicians call for obedience rather than awareness and appeal to our patriotism, not to our solidarity.

It is under the guise of these categorizations that we have already seen, across the world, shifts towards dangerous authoritarian power-grabs, as in Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán seized wide-ranging emergency powers and the ability to rule by decree.

Similarly, in the Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte, in the context of a national emergency bill, gained the right to punish people spreading “false information” about the outbreak, a right that could easily be used to silence political dissent.

In the United Kingdom, a country with robust democratic institutions, the Coronavirus Bill gave government ministries the power to detain and isolate people, ban public gatherings including protests and shut down ports and airports. Health Secretary Matt Hancock put it this way:

“The measures that I have outlined are unprecedented in peacetime. We will fight this virus with everything we have. We are in a war against an invisible killer and we have to do everything we can to stop it.”

In Alberta, the passing of Bill 10 gives the premier and his cabinet broad and extraordinary powers.

Moreover, defining the pandemic as war leads inevitably to the need to identify an enemy. The enemy here is the the coronavirus, but many politicians have also added qualifiers to the enemy virus.

The expression, “the China Virus,” by President Trump and other American policy-makers, has been linked to a rise of racist anti-Asian attacks in the North America.

As the virus has spread like wildfire in large cities like New York, Toronto and Montréal, another dichotomy is between big urban centres and smaller rural areas whose residents may feel at risk of exposure from city-dwellers escaping the metropolis.

A new nationalism

As we find ourselves at war we may be irresistibly drawn to an inward-looking, my-country-first attitude. Arguments over essential supplies have erupted, with countries blocking shipments of items like masks and other protective equipment or life-saving ventilators.

Within the European Union an initial failure of solidarity has made many suggest that the pandemic might eventually claim another victim: the EU itself.

The Trump administration has attempted to prevent 3M, the world’s largest manufacturers of protective medical gear, from sending masks to Canada. The attempt was promptly followed by a not-too-subtle reference by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to the large number of Canadian doctors and nurses crossing the border to work in American hospitals.

The long run

Experts have been increasingly talking about a large time window before we can expect this crisis to be over. Laboratories around the world are racing to find a vaccine or, at least, an effective treatment to reduce casualties.

In other words, we are in this for the long run: democracies and authoritarian states, rich and poor states, Chinese, Americans, Russians and the rest of the world.

If we are “at war” for an undetermined amount of time, battle fatigue may derail all efforts. Leaders would do better to promote civil responsibility and global solidarity instead of the idea of warfare. Finding a solution to the pandemic is a shared responsibility, and the solution must be global.

It is not by cultivating the image of warriors that governments will convince people to continue to comply with health authorities: it is by appealing to civic duty, solidarity and respect for fellow human beings.

This shift in perspective is necessary, if we want to resolve not only this crisis, but other global emergencies, including climate change and the depletion of the planet which are, as the World Health Organization has indicated, inextricably linked with the spread of infectious diseases.