For every medical condition, treatments are most effective when measurement guides the choice of therapy and its effects. Just think of diabetes, where blood glucose levels guide the choice of treatment then measure its effectiveness.

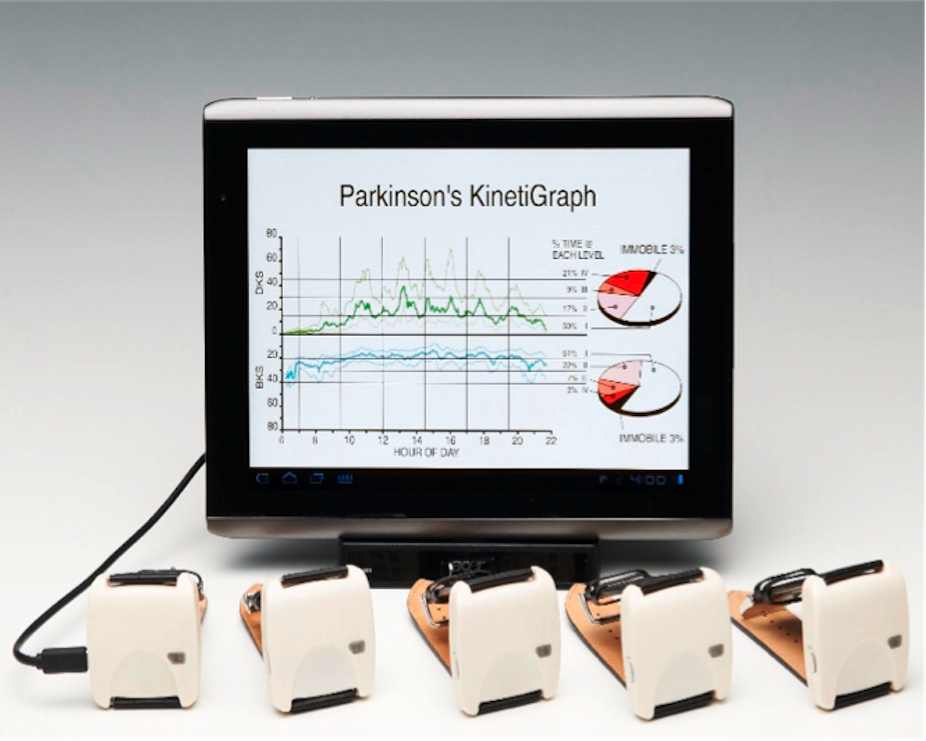

Until now there’s been no objective measure to guide therapy for Parkinson’s disease, which affects more than six million people globally. But my colleagues and I at the Florey Institute think we’ve found an effective and inexpensive way to do it: the Parkinson’s KinetiGraph (PKG) uses advanced technology to measure and assess Parkinson’s sufferers’ treatment.

Measuring up

In a single day, people with Parkinson’s oscillate between the slowness and disability of undertreatment and the trying, involuntary movements of overtreatment. They struggle to accurately communicate this message to their doctors. If an experienced specialist takes time, much can be gleaned from the patient; although, even in this circumstance, admission to hospital for observation may be required.

Many patients, especially in regional areas, do not have access to doctors with the experience or time to address and analyse their symptoms, so what’s needed is an objective measure of the everyday movement abnormalities of people with Parkinson’s - and this measure also needs to take into account the consumption of medications.

In untreated Parkinson’s, movements are described as bradykinetic, a word with Greek origins, literally meaning “slow movement”.

In treated Parkinson’s, medications may produce excess troublesome movements called dyskinesia (bad movements).

For a long time, these movements were considered to be fundamentally different to normal movements.

Just like starting over

Over a long period of time analysing the movements of Parkinson’s sufferers, our research team at the Florey Institute came to the conclusion these movements were not necessarily “abnormal”, but rather normal movements made in the wrong context.

Consider the process of learning to drive. Initially, the learner driver’s attention is directed at co-ordinating clutch, brakes and gears. Steering and movements at this stage are slow, uncoordinated and with too many pauses between them. As they become natural they become smoother and faster and no longer require intense attention. The driver can then focus on negotiating traffic and external happenings.

This process of making things natural and automatic is controlled by the part of the brain - frontal lobes, basal ganglia, substantia nigra - affected by Parkinson’s. For people with Parkinson’s disease, automatic movements are not easily accessed and are made as if they were being newly learned.

On the other hand, overtreatment of Parkinson’s may produce an excess of automatic movements, which are unnecessary, without purpose and have too little time between them.

Put another way, bradykinesia is the propensity to make slow movements with more and longer pauses between them; dyskinesia, comparatively, is the tendency to make an excess of automatic movements with too few gaps in between.

Keeping watch

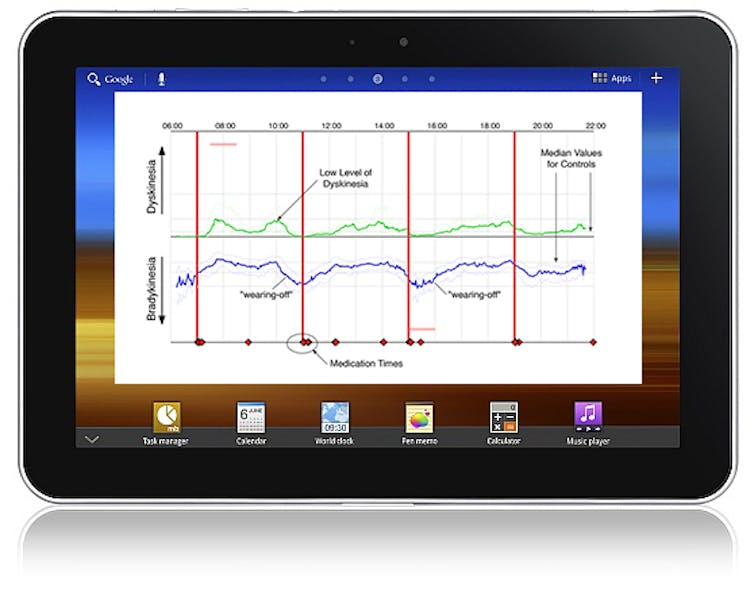

Our team at the Florey placed sensors on the limbs of Parkinson’s sufferers to measure acceleration as a means for measuring movement. They then developed two algorithms: one to produce a bradykinesia score and the other to produce a dyskinesia score. The accelerometer output was recorded continuously over the day and night and the algorithms use the data to produce a score every two minutes.

Global Kinetics Corporation was formed in Melbourne in 2007 to take the algorithms and develop them into a system that could be readily used in routine clinical practice for the management of Parkinson’s disease. Their system is known as the Parkinson’s KinetiGraph (PKG) and comes in the form of a small wrist-worn device.

The device contains analysis systems that collect data and apply the algorithms to produce a report for the clinic. The device contains an accelerometer for measuring movements, sufficient memory to store the accelerometry data for more than 20 days, a reminder to patients to take their medications and a means for recording when the medicines were actually consumed.

The patient wears the device continuously, night and day, for ten days and then returns it to the clinic. The data is extracted, analysed and within ten minutes, put into a report that is emailed to the referring clinician.

The report shows how bradykinesia and dyskinesia vary over the time of day and in relationship to the timing of medications. It also shows compliance in taking medications. As well, the research team has shown that when the PKG’s bradykinesia score is very high, then it is almost certain that the person is asleep. As daytime sleepiness and nighttime insomnolence is a major (but treatable) problem in Parkinson’s, the sleep data can be a major aid in better management.

A further and surprising development is the ability to detect impulse control behaviours which are common in Parkinson’s and cause serious damage to family relationships.

The PKG System is now used in routine clinical care in leading centres in Australia, Europe and the UK. In these clinics, patients wear the PKG prior to their consultation so that the report is available to the clinician at the time of consultation.

Feedback from clinicians suggests that for approximately 30% of patients using the PKG, the device provides information that would not otherwise have been known. This is important in managing dosage, side-effects and, importantly, the timing and management of surgery for insertion of deep brain electrodes.

The PKG provides the clinician with objective measurement that allows them to manage Parkinson’s with the same precision that they can manage disorders such as diabetes.

As mentioned at the outset, better measurement of medical conditions equals better treatment – and we believe we’ve come up with a workable solution on this front.