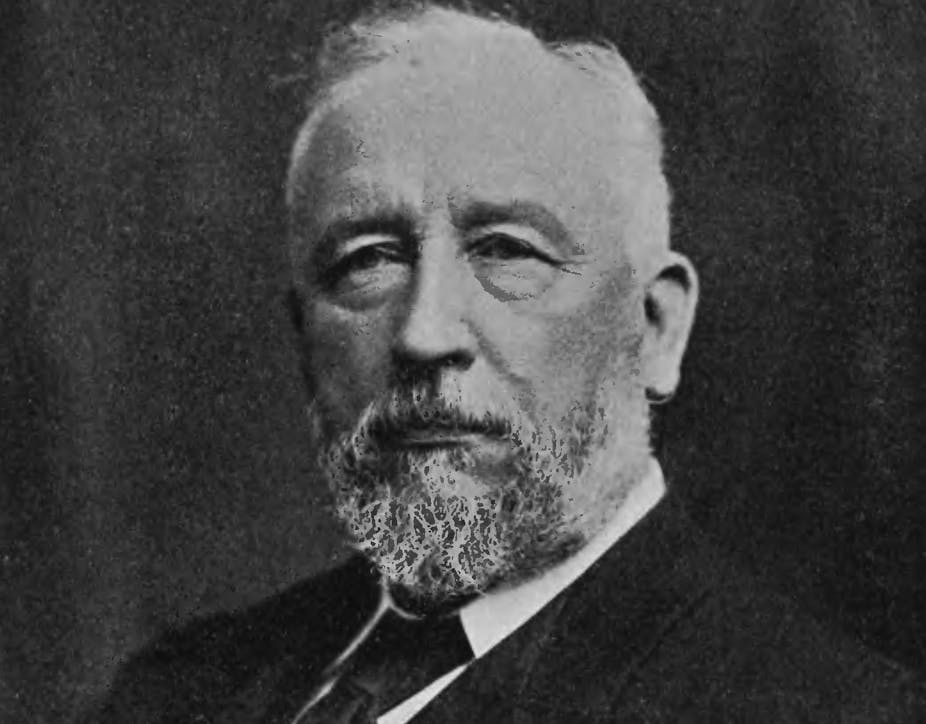

There have been 10 astronomers royal for Scotland since the honour was created in 1834, only three of whom were Scots. I believe Aberdonian Sir David Gill (1843-1914), who never held the honour, trumps them all. This year is the centenary of his death and a good time to celebrate his achievements.

Gill appears to be the only Scot to have been awarded the Bruce Medal for lifetime achievement in astronomy; the only Scot to have been awarded the Watson medal for outstanding astronomy by the US National Academy of Sciences; and the only Scot to have been awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society twice.

I could go on. Knighted KCB by Queen Victoria in 1900, he was honoured, respected and admired by the worldwide community of astronomers - and by others too, as we’ll see.

Timely beginnings

Gill began his adult life as a successful watchmaker. By day, David Gill & Son were watchmakers to the Queen (our David was the son), located on Aberdeen’s main thoroughfare, Union Street.

By night, Gill was an amateur astronomer. The chance to change his life came one day in December 1871 when he was offered the directorship of Lord Lindsay’s impressive Dunecht Observatory located about 13 miles west of Aberdeen.

Not many people know that Aberdeenshire had a world-class observatory. Through the 1870s, Gill showed himself as a man supremely at home with the most complex of astronomical instruments. He was a man with the patience to make high-precision observations; who could organise international expeditions; and who knew what he wanted to discover in astronomy – among them constants in the measurement of heavenly bodies that were more accurate than any being used at the time.

His talents were such that in early 1879, against strong conventional competition, he was appointed her majesty’s astronomer at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The decision was made by the first lord of the admiralty, WH Smith, the same one whose family business of railway station news agencies was thriving.

It was an inspired choice for astronomy, South Africa and the admiralty. Over the next 26 years Gill raised the profile of the Royal Observatory at the Cape to the premier observatory in the Southern hemisphere. It became a meeting place for intellectuals, artists, musicians and distinguished visitors as well as for both practical and scientific astronomers.

Measurement man

Meticulous observation coupled with precision instrument design was Gill’s forte, in what nowadays would be known as astrometry. Gill provided a number of definitive astronomical constants used to create nautical almanacs throughout the world, constants such as the mass of the moon, the scale of the solar system, the wobble of the Earth’s axis. This led to better almanacs, helping to make navigation at sea more accurate.

In particular he spent years working out the average distance from the Earth to the sun, which is vital for calculating the scale of the solar system. This distance is the yardstick used to measure all stellar distances. He took it from having an accuracy of +/- 4% at the start of his career to within 0.1% of modern values.

Gill’s measurements of stellar distances were the most reliable of his time. One of the new insights they made possible was that faint and bright stars were not just like that due to their varying distances from us but also because stars themselves varied widely in brightness. Nature was found to be more diverse than had been imagined.

One of Gill’s achievements was to publish in collaboration with the Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn the first stellar catalogue produced from photographs, containing over 400,000 Southern hemisphere stars.

Gill was also a driving force and president of the International Astrographic Commission that organised the biggest international astronomical project ever undertaken, the Carte du Ciel (“map of the sky”) which aimed to produce a stellar catalogue of several million stars and a multi-sheet map of the heavens. For each of the stars it contained, the catalogue gave its precise position in the sky and how bright it was.

Gill’s lost century

Despite these achievements, for much of the 20th Century Gill’s name didn’t appear in textbooks because astrometry fell out of favour. Astrophysics took over on the back of discoveries such as nuclear physics and Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Now the wheel of fortune has slowly turned and over the past two decades, astrometry has come back into fashion as scientists have become more interested in questions such as how galaxies form and evolve. Today’s technology using space probes and satellites can do so much more than late 19th-century telescopes.

There’s one thing that it can’t do, though – tell us what the skies were like a century ago. Gill’s legacy of precision measurements made in the 19th and early 20th centuries gives modern astronomers the huge bonus of being able to investigate stellar motion and stars of varying brightness over a long time-scale.

This is not the end of the David Gill story. During his time at the Cape he also became the unofficial director of the geodetic survey of South Africa and pushed forward the establishment of some 500 reference trigonometric stations from which topographical surveys were made.

It was the best survey backbone in the southern hemisphere, covering an area that in European terms would stretch in latitude from the Mediterranean to southern Norway, in longitude from London to Prague. Gill saw this effort as necessary for the development of South Africa and also to improve knowledge of the size of the Earth, a vital link in the chain for deducing how far away stars are from us.

David Gill retired to London, joining the council of the Royal Geographic Society; becoming president of the Royal Astronomical Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science; the British representative on the International Weights and Measures Commission and much more.

Few British scientists of the 20th Century have been so widely honoured and so well respected as Sir David Gill. Scotland’s most notable astronomer? I think so. Maybe someone inspired by National Science and Engineering Week, which runs until March 23, can take away his mantle in a few decades time.