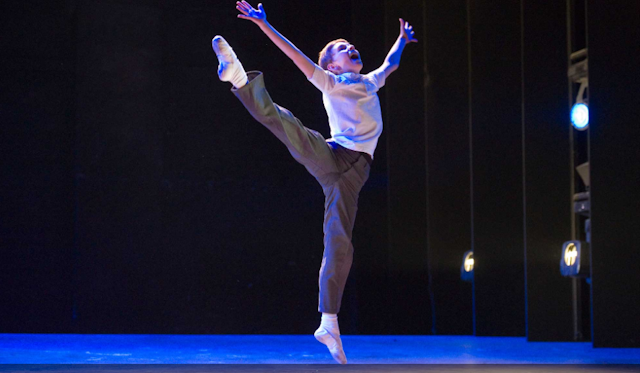

If Billy Elliot taught us one thing, it was that dance isn’t just for girls. Now the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) has launched a new project which aims to get more boys on the dance floor and into ballet shoes. It’s a fine aspiration and one which needs more support – but is it really necessary to delve into stereotypical “male” tropes like football and superheros to encourage the next generation of male dancers to come forward?

Professional male ballet dancers, such as Iain Mackay and Alexander Campbell, have been recruited as RAD “Dance Ambassadors” who will reach out to young boys with masterclasses and workshops. Such role models are not new, of course – think of star names like Fred Astaire, Rudolph Nureyev and Carlos Acosta.

But so far, these big names don’t seem to have made much difference. Boys have hardly been flocking to dance classes – fewer than 2% of the RAD’s ballet dance examination candidates are boys. Plus, there have been plenty of amateur male role models appearing on Strictly Come Dancing. Remember cricketer Darren Gough, gymnast Louis Smith, singer Jay McGuiness and sports presenter Ore Oduba?

Have they inspired males to take up ballroom dancing – or any other sort of dancing for that matter? My experience, as a seasoned dance teacher, coupled with my research exploring the experiences of young male dancers, aged eight to 18, suggests not.

All too often, young male dancers recount similar stories: enduring stigma, bullying and marginalisation. Some of this can be acute, especially if the dance styles they perform, like ballet, are deemed “feminine”. So, let’s hope these new “Dance Ambassadors” can help to banish some of the myths that surround boys who dance, especially the one concerning male dancers and their sexuality. Dance is for all boys, as it is for all girls, irrespective of their sexual orientation.

Sports and superheroes?

Project B attempts to draw parallels between dance and sports, firing boys’ imaginations with “new dance partnerships inspired by sports and superheroes”. It is their “cool” moves that boys want to do, according to Mackay, who talks about the Usain “Bolt”, the Transformer pose, the Christiano Ronaldo jump. For Mackay, dance is about “jumping and posing like superheroes, spinning across the room like Angry Birds or creating patterns and shapes like building blocks in Minecraft”.

And yet, is this really what we want boys to emulate? Or should we aspire to move beyond such normative masculinity and instead move towards one that’s more inclusive, one that more accurately reflects the range of contemporary masculinities?

We could start by having boys dancing together in newly-created dance repertoire. It doesn’t all have to be Giselle or The Nutcracker, beautiful though they may be. Matthew Bourne’s male Swan Lake led the way, so let’s follow his example of reimagining the role of the male dancer. Heroism isn’t a male preserve, so if we want to promote the “athleticism and physicality that ballet holds”, as is MaKay’s aspiration, I think we need to ditch the “superheroes” and instead showcase a range of performers across the gender spectrum.

Plans for Project B include more boys’ only workshops and masterclasses, plus bursaries and financial support for regular tuition – a valuable initiative in enabling more boys to take that first vital step into dance. Single-sex tuition could be very beneficial to boys who would benefit from peer support and, one hopes, gain greater confidence in their dancing and overcome any criticism they might encounter.

But who will teach these new male dancers? Project B offers financial support to encourage more men to train as dance teachers, as well as providing new resources for existing teachers. It would be great to have more male dance teachers to help inspire a new generation of male dancers and to redress the workforce gender imbalance.

But these nascent male teachers will need time to train and so the RAD’s additional commitment to producing “new resources for existing teachers” is to be warmly welcomed – not least because my research indicates that some private sector dance schools are, understandably, inexperienced in teaching boys and would welcome guidance in how best to support them.

Specialist dance teachers

Beyond Project B, can more be done to encourage boys into dance? The answer is yes. Better dance provision in schools, and more of it, would be a start. Delivered by specialist dance teachers to ensure a high-quality offering for all students, irrespective of their gender. And while there’s a dearth of specialist dance teachers in schools, why not reach out to private sector teachers and utilise their skills?

Coordinated action across the dance sector will be essential if we are to turn the tide. Project B is an important step in the right direction and there’s plenty of other work being done, too, such as the Boys Can Dance initiative at London’s The Place. But more sustained action to promote boys in a range of dance styles – in the media, online and, crucially, in schools – is also needed. Boys who want to dance, irrespective of genre, should feel able to do so. Otherwise, where will we find the next Billy Elliot?