There’s something to be said for the suggestion that politicians habitually cite academic papers they have never read and thus use them as convenient props for measures they would have implemented anyway. This argument has been advanced ever since doubts were first raised about the accuracy of Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s now-infamous research into the supposed links between high levels of public debt and protracted slow growth.

Even allowing for this possibility, though, we’re still left with the uncomfortable thought that things might have been different if policymakers hadn’t had this particular crutch on which to lean. They might, after all, have looked for another. They might even have conceded that the notion that “debt is dangerous” and that austerity therefore represents the sole means of restoring economic growth doesn’t necessarily withstand close examination.

As it is, it seems the presence of a common turning point beyond which debt’s detrimental impact on growth becomes significant or notably increases remains a given in certain policy circles. Moreover – and it’s easy to forget this when much of the academic trench warfare of the past year has been conducted in the US – this enduring consensus isn’t confined exclusively to those charged with salvaging the world’s largest economy.

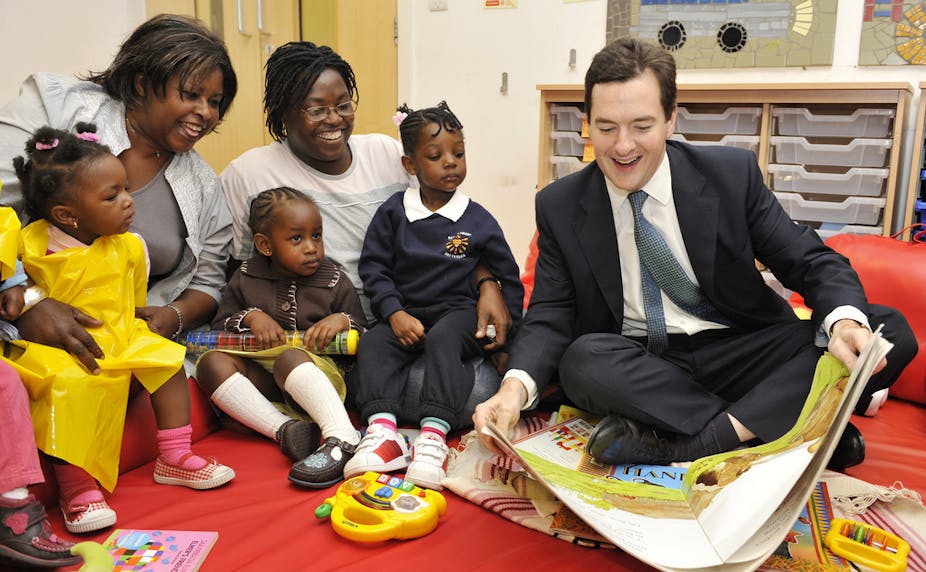

In the UK, for example, Chancellor George Osborne, speaking at the Conservatives’ annual party conference last September, warned that the repercussions of the financial crisis would be felt “until we’ve fixed the addiction to debt that got this country into this mess in the first place”. Four months later, crediting his policies with helping Britain’s economy to grow faster than any of its major competitors, Osborne was unequivocal in his message: austerity works.

But how can we be sure austerity works if the causality routinely used to excuse its application doesn’t exist? The vast majority of empirical studies into public debt and growth have assumed a shared threshold beyond which economies tend to contract rather than expand. But if debt-growth dynamics differ across countries then one-size-fits-all policies are at best misleading and at worst potentially counterproductive.

A study I conducted with Andrea Presbitero of the IMF addresses this question. Using data on total public debt for 105 developing, emerging and developed economies from 1972 to 2009, we found tentative evidence that nations with higher average debt-to-GDP ratios are likely to experience slower economic growth in the long-run; yet we found no evidence that a specific debt threshold common to all countries – Reinhart and Rogoff’s near-legendary 90%, for instance – invariably triggers a slowdown.

I reached the same conclusion after carrying out related research that examined two centuries’ worth of data for the UK, the US, Sweden and Japan. Both studies cast serious doubt on the fundamental assumptions at the core of major economic policies and/or their political justification. If the debt-growth relationship varies across countries, as these findings imply, it follows that policies for one country may be seriously misguided if applied in another.

For Reinhart and Rogoff, of course, ignominy is piled upon ignominy, despite the fact that in other work they write that any debt thresholds are likely to differ across countries. They have found their work – and themselves – under near-relentless attack. Their pursuit by some commentators has bordered on a witch-hunt. All wrath is visited upon them and them alone. As Kenneth Williams’ Julius Caesar so memorably lamented in Carry On Cleo: “Infamy, infamy – they’ve all got it in for me.”

Yet it’s perilously easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. The sheer ferocity of the academic debate has somehow served to obscure its value as precisely that: the expressing of grave reservations about the approach and conclusions of empirical analysis that in some political quarters has been accepted with all the determinism of a pharmaceutical randomised control trial.

That Reinhart and Rogoff ever intended their work to be linked to the austerity debate is a moot point. But what’s harder to deny is that policymakers have selectively relied on their paper to paint the debt-growth conundrum as a fait accompli, offering neither acknowledgement of any reservations nor, more crucially, even a hint that some degree of reconsideration might be in order.

Irrespective of whether the decision-makers in question have genuinely read Reinhart and Rogoff’s Growth in a Time of Debt or have merely heard heartening tales of it from their advisers and mandarins, it’s time to find another prop and perhaps even another direction. Economists aren’t lab workers in white coats, and policymakers shouldn’t selectively present our work as the stuff of cast-iron certainty – especially when the academic discussion surrounding it suggests it’s anything but.

We still don’t have convincing proof that austerity works; and until we do, until the credo can bear the most intense scrutiny, it’s wrong – not to mention inherently dangerous – to infer that this prevailing cornerstone of post-crisis thinking is unshakably firm and exempt from uprooting.