One month after Robert Mueller submitted the final report on his investigation into Donald Trump, its contents have finally been made public – meaning that the Department of Justice is no longer the only one analyzing and interpreting Mueller’s findings.

Attorney General William Barr has publicly stated his belief that Mueller’s inquiry exonerates the president of criminal wrongdoing. Now, the American public will get to draw its own conclusions.

Congress, state prosecutors and district attorneys nationwide, too, are digging into the Mueller report to decide whether Mueller found evidence that Trump obstructed justice, colluded with Russia or committed any impeachable offenses. Beyond Mueller’s federal inquiry, a dozen city and state prosecutors have launched investigations into possible criminal wrongdoing by Trump, his family and his business.

As Mueller’s investigation evolves from political saga to legal analysis, here are three key threads our experts have been watching.

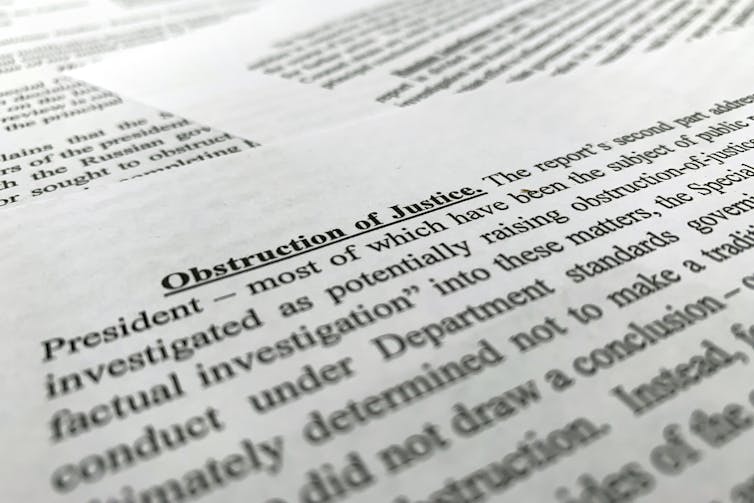

1. Obstruction of justice

Barr’s determination that Trump did not commit obstruction of justice differs from the conclusion Mueller drew in his own report. According to the special counsel, “while this report does not conclude that the president committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.”

How can two people draw different conclusions from the same evidence?

“Obstruction of justice is a complicated matter,” writes law professor David Orentlicher of the University of Nevada-Las Vegas.

According to federal law, obstruction occurs when a person tries to impede or influence a trial, investigation or other official proceeding with threats or corrupt intent.

“Bribing a judge and destroying evidence are classic examples of this crime,” Orentlicher says.

But other actions may constitute obstruction too, depending on the context. And some actions that look like obstruction may not be, because the law requires a “corrupt” intention to obstruct justice as well.

President Trump did many things that influenced federal investigations into him and his aides, Orentlicher points out, including firing FBI Director James Comey, publicly attacking the special counsel’s work and pressuring former Attorney General Jeff Sessions not to recuse himself from overseeing Mueller’s investigation.

The legal question Congress and prosecutors nationwide must now determine is: Did he do so with “corrupt” intent?

2. Who does the attorney general work for?

In the April 18 press conference, Barr cited the White House’s “full cooperation” with Mueller’s investigation as evidence of “noncorrupt motives.”

Critics of the attorney general contend that Barr is not an objective authority on Trump’s behavior since he is a political appointee picked by Trump.

Barr, a veteran lawyer who previously served as President George H.W. Bush’s attorney general, also believes the Constitution gives the president almost unlimited power, says Austin Sarat, a political scientist at Amherst College. Barr has referred to the attorney general – the government’s top prosecutor – as “the president’s lawyer.”

So who does the attorney general work for? The question dates back centuries.

“The office of attorney general is not mentioned in the Constitution. It was created when the First Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789,” Sarat says.

That law that laid out such limited duties for the role that “the attorney general was to be a part-time official” reporting to the president, according to Sarat.

As a result, “throughout American history, there have been different visions of the role of the attorney general,” he writes.

3. Impeachment

Congress won’t only be reading Mueller’s report to determine whether Trump committed obstruction of justice. It’s likely that some Democratic lawmakers will also be looking for any indication that the president committed an impeachable offense.

In his report, special counsel Mueller appears to have acknowledged Congress’s role in going beyond the findings of his report.

“Congress has authority to prohibit a President’s corrupt use of his authority in order to protect the integrity of the administration of justice,” he wrote.

The U.S. Constitution states that the president can be removed from office after being both impeached and convicted for “Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

What exactly constitutes a “high crime” or “misdemeanor,” however, has always been open to interpretation, says University of Buffalo political scientist Jacob Neiheisel.

President Bill Clinton was impeached in 1998 for perjury and obstruction of justice during the investigation into his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Articles of impeachment brought against President Richard Nixon in 1974 after Watergate accused him of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress.

Neiheisel believes that “the articles of impeachment against Trump might look remarkably similar to those levied against Nixon and Clinton.”

Lawmakers actually drew up articles of impeachment against the president well before the Mueller report was released.

In November 2017, “five Democrats in the House accused the president of obstruction of justice related to the firing of FBI director James Comey, undermining the independence of the federal judiciary, accepting emoluments from a foreign government and other charges,” says Neiheisel.

House speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Democratic leaders have previously sought to tamp down any discussion of impeaching Trump, believing that this extreme option should be pursued only if the evidence against the president was so compelling that impeachment proceedings would have broad bipartisan support.

Now that Mueller’s report is out, the debate over impeachment will arguably be much harder to quash.

This article is a round-up of stories from The Conversation’s archive.