The recent discovery of a well preserved early modern shipwreck in the mudflats of Tankerton Beach near Whitstable, Kent, is a highly significant archaeological find. Not only can it provide important information on early modern shipbuilding techniques, it can also provide valuable insights into the maritime trade of late Tudor and early Stuart England.

Archaeologists have reportedly subjected the ship’s oak planks to dendrochronological sampling, a process which dates timber through an analysis of ring width of trees. The tests revealed that it was felled in a southern British woodland in 1531, while three other samples of different timbers have been provisionally dated to the 16th century.

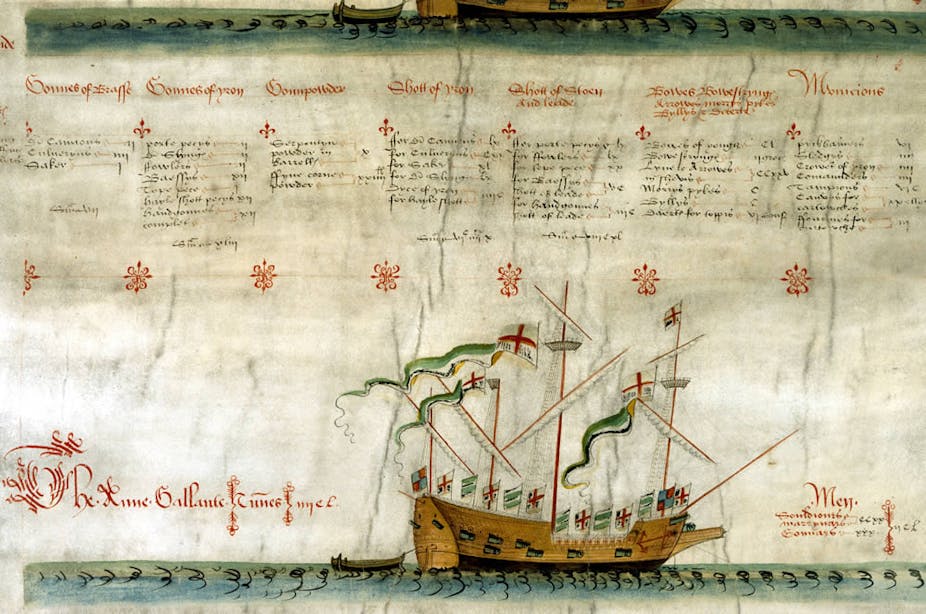

The hull’s construction suggests that the vessel is a late 16th or early 17th-century carvel-built, single-masted merchant ship. This was a process whereby a hull’s planks were fastened to a frame, with their edges flush against one another – as opposed to clinker building, where the planks overlap along their edges. The wreck is 12.14 metres long by five metres wide and estimated to have been between 100 and 200 tons (the carrying capacity of a vessel in Bordeaux wine casks, or “tuns”, at about 954.7 litres, or 210 gallons, a barrel – the common measure used in England at the time).

It is the only known wreck of this period in the south-east of England. The Department for Culture, Media, and Sport, on the advice of Historic England, has therefore scheduled the wreck as one of national importance, giving it protected status.

It is difficult to say at this stage whether or not the ship is an English vessel. The provenance of some of its timbers would suggest it is – but it could equally be Dutch or German-built. The wreck’s location – close to a series of well-known copperas (iron sulphate, also known as green vitriol) works in northern Kent – has led to suggestions that the ship was involved in the trade of this important commodity which was used in dying and tanning and in the production of ink.

But without further investigation it is difficult to know whether this is the case, or whether the vessel’s final resting place was by accident or design – it may have been abandoned on the coast in an area that was once a tidal salt marsh.

Large for its time

Whether it is an English ship or not, a merchant ship of 100–200 tons was atypical of the vast majority of merchant ships operating in northern European waters in the 16th century. Recent research into the merchant fleet of medieval and Tudor England, using the English national customs accounts which record seaborne trade (of both English and foreign ships), allows us to place the ship found in Kent within the wider context of the merchant fleet of the period.

The research found that most 16th-century English merchant vessels in the period (1565–1580) were on average between 20–30 tons burden (carrying capacity). English seaborne trade in this period was predominantly coastal, with voyages between English ports. This coastal trade was undertaken by ships of all sizes, but the majority of cargoes were carried in ships of less than 100 tons; fewer than 1% of coastal trading voyages from 1565–80 were by ships of 100 tons and over.

Smaller ships (that is to say ships of 50 tons or less) also dominated overseas trade, but large ships of 100 tons and over were far more prevalent in overseas activity – 25% of overseas voyages by English ships were undertaken by vessels of 100 tons and over. It was a similar case for foreign ships trading with England. Though one might expect foreign vessels to be bigger, especially if they came from further away places such as Spain, the English customs accounts reveal that about 90% of foreign ships trading with England were 50 tons or less. At 100–200 tons, the Kent ship was therefore in the top tier of merchant ships active at the time.

Trading places

The ship’s size also hints at the voyages it may have undertaken. The final decades of the 16th century, and the first decades of the 17th, were important in the development of England as a maritime nation. Some overseas trade routes, such as those between England, France, and the Low Countries – even those to farther flung destinations such as in the Baltic, Spain, and Portugal – had been traversed since the Middle Ages. But others were new.

As the merchant fleet increased in size and tonnage after about 1580, so too did the places with which English vessels traded. Large Tudor merchant vessels travelled to Russia, North Africa, the Azores and, by the last decades of the 16th and early 17th centuries, began traversing the Atlantic with increasing frequency and rounded the southern tip of Africa into the Indian Ocean.

They brought back with them increasingly exotic goods: silk, sugar, pepper, currants, and crops from the Americas such as the potato and maize, and many other exotic goods. The Kent ship may well have been involved in this slow but steady growth of overseas trade.

Excavations underway by Wessex Archaeology will hopefully discover more about the vessel’s provenance, usage, and some personal effects of the ship’s crew, shedding invaluable light on a ship that sits at a critical juncture in the development of an English maritime empire.