Comparatively speaking, these are successful times for Britain’s Green Party. They have their first elected MP at Westminster, two Members of the European Parliament, two Members of the London Assembly, and 141 local councillors following the 2013 local elections. Those who turn up to the annual conference in Brighton this weekend can attend sessions on “Food poverty and benefit cuts: the living reality”; “What next for the LGBT struggle after same-sex marriage?”; and “Immigration: busting the myths and winning the argument”. For downtime there is the Hullabaloo Quire singing “songs of protest and celebration from around the world”.

We might ask what practical difference the Green Party makes to British politics, and how well they fulfil the role expected of political parties in a democratic system. Typically, that would be representing a section of the population, thereby forming a link between government and the people, legislating and organising government, and mobilising the electorate through political campaigns.

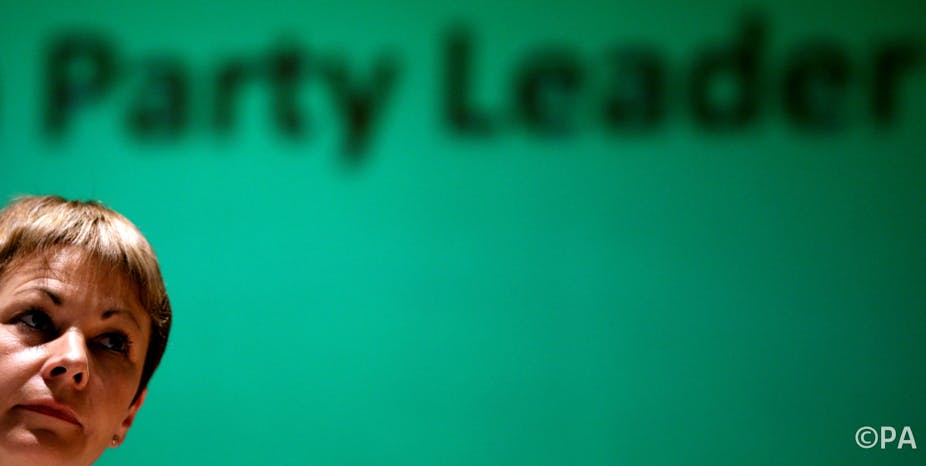

There are two arguments that suggest the Green Party is now irrelevant to UK politics. One paints greens as victims of their own success – environmental politics may once have been a fringe concern, but environmental concerns have migrated into mainstream political thought, and this has marginalised single-issue environmental parties. For example, some years prior to the election of solitary Green MP Caroline Lucas, Parliament passed the Climate Change Act, which commits the UK to legally binding targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an ambitious 80% by 2050 compared to emissions of 1990. Another piece of legislation which assigns government funding to research carbon capture and storage technology, the Energy Act, was passed in 2010. And of course the UK is subject to numerous European Union laws, conventions and regulations governing environmental matters. If the mainstream parties can achieve this by themselves, why do we need a Green Party?

A second point is that, if sections of the public still want to lobby for representation and political action on environmental matters dear to their hearts, there are many campaigning charities, NGOs and activist groups willing to pick up the mantle. Concerned about climate change? Well so is the Campaign against Climate Change, Rising Tide, Stop Climate Chaos, and Plane Stupid, not to mention older hands such as Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and the WWF. The protection of marine species? Look no further than the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. Fracking? Frack Off.

For every manifestation of every aspect of environmental concern there is almost certainly a relevant campaign group engaged in anything and everything from letter-writing to handcuffing themselves to bulldozers. The danger here for the Green Party is that it is squeezed between the kind of legislation it endorses emanating from mainstream parties, and the direct forms of political engagement offered by environmental campaign groups.

So are the delegates to the Green Party conference wasting their time when they sit down to discuss “Greener Cities: from vision to reality”? Can they ever hope to translate their own aspirations into reality, through the vehicle of the Green Party?

Even if there never is, as the party’s website puts it, “a Green government [that] will have the courage to pursue responsible solutions to our social, economic and environmental crises”, it’s not necessarily the case that the existence of a Green Party is irrelevant.

The Green Party’s vision involves some sixteen different policies, from the economy through transport to animal protection. The political space that the Green Party inhabits arises from the fact that, despite its emphasis on environmental questions, it is not a single-issue organisation. The party has developed, as must any political party with serious aspirations, a range of policies across many areas that are ideologically linked together to offer a distinctive alternative to the electorate.

And “politics” is much more than what happens in the Westminster Village: those 141 local councillors can make a difference to people’s day-to-day lives in a way that single-issue campaigners never will. Via Brussels, the Green Party links up with its European partners to influence EU policy. In fact it is on the continent that the green parties are able to wield more power, in European nations whose proportional electoral systems give better results to smaller parties that the first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all system in the UK. The apparent “irrelevance” of green parties depends very much on where you look: greens have participated in coalition governments in Australia, Germany, France, Finland, Belgium and Ireland.

The titles of two Green Party conference sessions are particularly telling: “How should Greens break into mass popular awareness as UKIP have done?” and “Constructing a popular Green narrative”. Both indicate a self-awareness of the Green Party’s peripheral status in British politics. Gone are the heady days of the 1989 European Elections when the UK Green Party won almost 15% of the vote (but no seats) and believed themselves on the verge of an electoral breakthrough.

In a democracy political parties serve a wider function than just winning elections, and the Green Party - true to its interests - plays a role in preserving the ideological biodiversity of the UK political landscape.