In Game 5 of the American League Division Series (ALDS), Toronto Blue Jays outfielder Jose Bautista faced Texas Rangers reliever Sam Dyson in the seventh inning with two runners on base, two outs and the game tied 3-3.

With the count 1-1, Bautista turned on a 97 mph fastball, hitting it into the upper deck of the Rogers Centre. Bautista tossed his bat into the air: a triumphant moment for the 34-year-old all-star – the biggest swing of his career, and the second-biggest for the franchise, after Joe Carter’s 1993 World Series-winning home run.

But after the game, Dyson seemed angrier about the bat flip than giving up the home run.

“Jose needs to calm that down,” Dyson said. “Just kind of respect the game a little more.”

Dyson’s comments came a couple of weeks after USA Today sportswriter Jorge L Ortiz asked San Diego Padres pitcher Bud Norris about a study that said the majority of bench-clearing incidents in Major League Baseball involved foreign players. Norris said that foreign players – particularly Latinos – needed to show more respect for the game.

“If you’re going to come into our country and make our American dollars,” Norris said, “you need to respect a game that has been here for over a hundred years… There are some players that have antics, that have done things over the years that we don’t necessarily agree with.”

Norris didn’t explain what he meant by “antics,” or perhaps Ortiz didn’t ask. But Norris’s message was unmistakable. If Latinos want to play baseball here, they need to “speak American,” in the words of former GOP vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin.

The quotations from Dyson and Norris perpetuate the notion that foreign and nonwhite players are welcome to play the national game as long as they do so according to the customs and practices of baseball traditionalists.

So where did this attitude emerge from? And why does it persist today?

For minority ballplayers, a history of silence

Baseball has been played in the United States for more than 200 years and professionally for 150 years, and for most of that time, it has discouraged, condemned or excluded specific ethnic, religious or racial groups.

Major league baseball (MLB) prohibited blacks until after World War II. White sportswriters knew about talented black players who were good enough for the major leagues, but said nothing, participating in what black sportswriters called a “conspiracy of silence.”

The white press reluctantly accepted Jackie Robinson, who integrated the major leagues in 1947. Most sportswriters said nothing about pitchers who threw at him, opponents who spiked him, and opponents and fans who cursed him with the vilest of epithets. When, after years of withholding his emotions, Robinson asserted himself, arguing with umpires and responding sharply to racist opponents, he was criticized by the press as ungrateful and uppity.

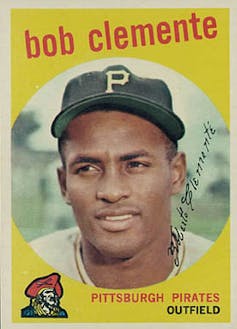

When Latinos followed blacks into baseball in the 1950s and 1960s, sportswriters quoted them in pidgin English and anglicized their names. Roberto Clemente became Bob Clemente. Latino players, living in a foreign country and speaking only rudimentary, if any, English were characterized as temperamental if they were introverted and hot-blooded if they demonstrated emotion.

Over the last few decades, the numbers of Latinos who played in the major leagues have risen steadily. When the 2015 baseball season began in April, nearly 30% of MLB players were Latino.

Many of these players were signed by unscrupulous agents – also called “buscones” – who lure adolescent ballplayers from their schools with promises of million-dollar paydays. After being placed in baseball schools, the young prospects learn to hit and field but are given little to no schooling on anything unrelated to baseball.

For the relative few who make it to the major leagues, money is plentiful but empathy scarce. Several major league managers speak Spanish. But only one, the Atlanta Braves’ Fredi Gonzalez, grew up in a Latin American country (Cuba).

If white players can tip their cap, why can’t Latinos flip their bats?

The most disappointing thing in USA Today’s article is the study that formed the basis for the article. Perhaps Ortiz or one or more of his editors ignored or deleted the context – historical and otherwise – necessary to give the study the background it needed. By doing so, a lot of readers concluded that recalcitrant Latinos were intent on ruining the sanctity of major league baseball.

Of the 67 bench-clearing incidents in major league baseball over the last five season, the study concluded, 87% of “the main antagonists hailed from different ethnic backgrounds.” What does “different ethnic backgrounds” mean? Different from what?

The most incendiary part of the study was the word “antagonist.” How did the study define the word? The story didn’t say. But the article did emphasize that Latino players were likely to be the antagonist. Why? Because they’re hot-blooded, right?

In his article, Ortiz quoted Alan Klein, a professor of sociology at Northeastern University in Boston who has written two books on Dominican baseball. Klein said antagonism was more likely to come from white rather than Latino players.

“There are white guys who celebrate exuberantly,” Klein said. “But when the guy happens to have slightly darker skin, I think it becomes part of something larger. It’s not just a guy celebrating, it’s a Dominican celebrating.”

Why is it disrespectful for a Latino player to flip his bat after a home run, but acceptable for a white player who hits a home run to leave his dugout after rounding the bases to tip his hat to the cheering fans? What about a white pitcher who pumps his fist in the air after an important strikeout?

A 2013 game between the Miami Marlins and the Atlanta Braves illustrates the hypocrisy of celebrations – and how and when they can occur.

In the top of the sixth inning, Atlanta’s (white) rookie outfielder Evan Gattis hit a home run off Jose Fernandez, a rookie pitcher from Cuba. After making contact, Gattis stood at home plate and watched the ball clear the fence. This is called “showing up the pitcher” and tends to anger the opposing team.

In the bottom of the sixth, Fernandez exacted some revenge by hitting his first major league home run. He watched the ball clear the outfield fence before trotting around the bases. It bears repeating that this was his first major league home run and a pitcher hitting a home run is relatively rare in baseball.

When Fernandez got to third base, Atlanta third baseman Chris Johnson began jawing at him. Fernandez then spit into the dirt. Catcher Brian McCann angrily confronted Fernandez after he crossed home plate. The two exchanged words. Both benches emptied.

McCann said he was angry because Fernandez had showed up his pitcher.

“I just told him you can’t do that,” McCann said.

Why not?

Was Fernandez the antagonist?

If so, why him and not Gattis?