In May 1934, the Spanish Football Federation invited Sunderland AFC to Spain to help them prepare for the World Cup in Italy. For all their troubles now (they were relegated to England’s third tier in April), in the mid-1930s Sunderland were one of Europe’s strongest sides. As the Spanish sporting newspaper El Mundo Deportivo noted, they represented the “the essence of English football in its purest sense”.

Germany took a similar approach, playing against Derby County. But while the Nazi regime relished the chance to demonstrate their superiority against English opponents, in Spain the Sunderland tour was rather a chance to hold a mirror up to Spanish football – and indeed to Spanish society in general – and recognise its shortcomings.

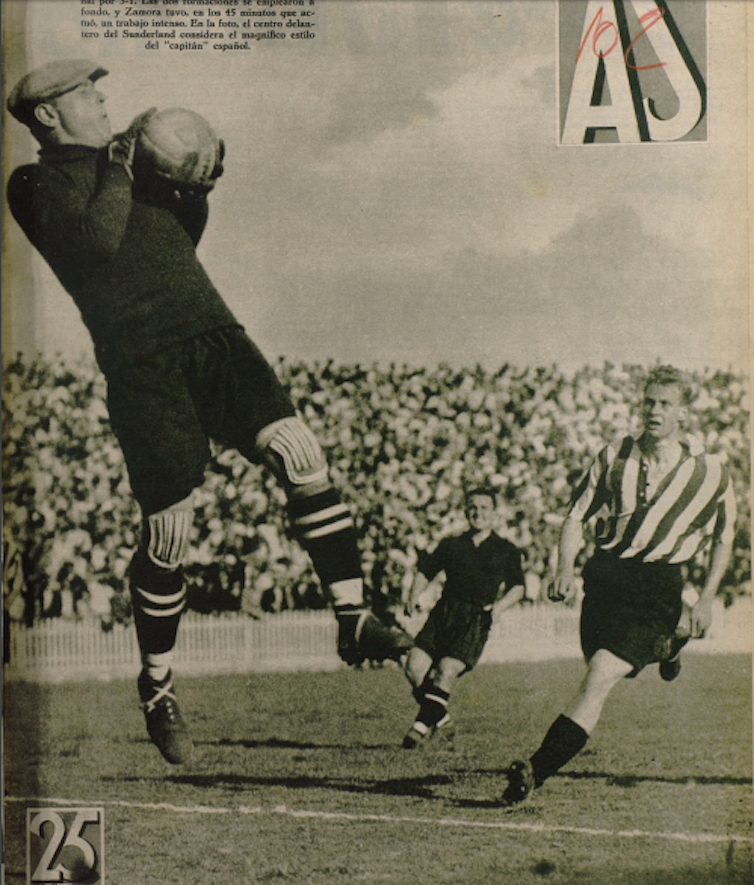

Three matches were played in just six days. The first, on May 14 in Bilbao, featured a more experimental Spanish XI. Most notably, Ricardo Zamora, Real Madrid’s goalkeeper and the undoubted star of Spanish football, did not feature. The match finished 3-3, with Sunderland scoring twice in the final minutes. A second match, at Madrid’s Chamartín stadium, finished in a 1-1 stalemate. Finally, the two teams met in Valencia where Sunderland beat Spain 3-1.

National regeneration

Far from taking heart from the series, the matches were held up as evidence of Spain’s footballing shortcomings. In the pages of the leading sports newspapers, Spain’s poor showing was blamed not solely on the players’ skills or the manager’s tactical acumen but rather on deeper faults. To a significant extent, the theories put forward in the match reports and associated editorials – and the language used to make such arguments – were representative of a wider debate concerning national regeneration (regeneracionismo) that had been dominating Spanish intellectual life for more than three decades.

Defeat in the Spanish-American War and the loss of Cuba in 1898 (known as El Desastre) caused many to question what was “wrong” with Spain. The answers put forward were many and varied. One common idea was that Spain had become physically weak or, in the words of writer, polymath and leading regenerationist thinker Joaquin Costa: “a nation of eunuchs”.

At the same time, several other thinkers lamented the perceived deficiencies of the Spanish people. As the essayist and politician Salvador de Madariaga argued: “Indifference, laziness and passivity are all part of the Spanish character. But above all, the Spanish are a profoundly individualistic people.”

From the turn of the century, team sports, most notably those imported from England, were recognised as one way of regenerating the “Spanish race”. Far from simply concerning themselves with gossip and match reports, the sporting press lobbied for individualistic, militaristic gymnastics to be replaced by team sports within Spain’s education system.

When the Second Republic was declared in April 1931, sport was seen as one means of building a new society, of converting the subjects of the Bourbon monarchy into citizens of a democracy. The prime minister, Manuel Azaña, himself noted:

Sport not only strengthens the body, but instils in those that practice it a spirit of cooperation, of subordination of the individual to the collective, and so contributes to correct the fierce individualism of our people.

The sporting press largely agreed – and saw in the May 1934 matches evidence to support their arguments. The English press praised the superior skills of the Sunderland players, as well as the “scientific tactical method” of manager Johnny Cochrane.

‘Just individuals thrown together’

In Spain, however, reports published in, among others, El Mundo Deportivo, AS and the more education-focused Educación Física attributed Sunderland’s dominance to other factors. They praised the speed, strength and fitness of the Sunderland players. Even though the English players had played more games over the previous season, AS noted:

Spain have shown a terrible tiredness … the players seemed completely exhausted and lacking any energy to make any real, sustained effort.

Indeed, their stamina – and conversely Spain’s lack of it – was seen as the reason the hosts conceded two late goals in Bilbao and one reason why they would struggle in Italy.

But above all, Spanish “individualism” was blamed for this difference in class. “Moving together, Sunderland were a harmonic unit like we have never seen before in Spain,” Educación Física concluded. Similarly, AS summed up the series by observing:

All the evidence shows that Sunderland is a team that can teach Spain a real footballing lesson: not a lesson in individual skill, but a lesson in playing as a team.

While for El Mundo Deportivo, the host’s shortcomings were similarly obvious: “The English are masters of football. Together, they play as one team – unlike Spain, who are just individuals thrown together.”

For all the pessimism, Spain were hardly humiliated in Italy. After a celebrated 3-1 victory over Brazil, they lost in a quarter-final replay to the hosts (arguably thanks to some questionable refereeing decisions). This was to be Spain’s last World Cup until 1950. By that point, Spanish football had been embraced as a propaganda tool by the Franco dictatorship.

Unlike during Spain’s shortlived experiment with liberal democracy, teamwork and a sense of collective spirit was no longer promoted as the idea. Instead, the Spanish press would denigrate the weakness of other nations, including their technicality and tactics. The directness and aggression of the “Furia Roja” (Red Fury – the popular nickname for the Spanish football team) was paramount and would arguably remain so for more than 50 years.

More evidence-based articles about football and the World Cup: