This article is part of the Democracy Futures series, a joint global initiative with the Sydney Democracy Network. The project aims to stimulate fresh thinking about the many challenges facing democracies in the 21st century. The essay is the first of four perspectives on the political relevance of anarchism and the prospects for liberty in the world today.

The following reflections on the subject of anarchism give a voice to the spirit of anarchy. By this I don’t mean what’s conventionally understood by the term: disturbance, disagreement and violent confusion triggered by the lack (an) of a ruler (arkhos). Rather, the perspectives published in this collection of essays brim with interest in the spirit of anarchism and its radical defence of unrestrained liberty, whose reality I first encountered on my hometown streets, with a wham and a whump.

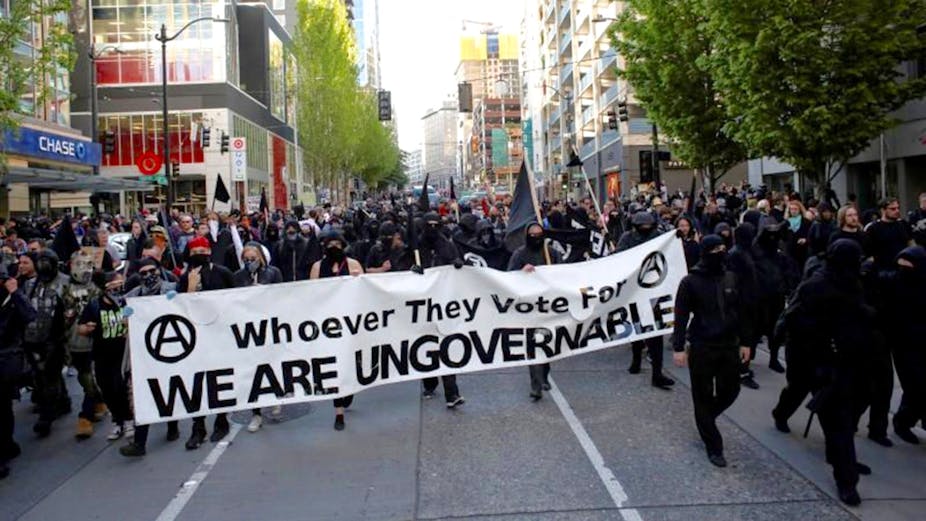

At the high point of public opposition to the Vietnam War, during a rush-hour sit-down by several thousand fellow students, riot police were summoned to clear the traffic snarl we’d caused at the main CBD intersection of our city. The picture below captures something of the swelling mayhem, as helmeted constables, wielding batons, came in on horseback.

To my astonishment, in the midst of tumult and turmoil, the anarchists in our ranks cool-headedly whipped out bags of marbles from deep inside their pockets. Unused to rollerskating, the horses grew unsteady; frightened, they began to rear up and draw back from the crowd. The anarchist tactics were simple, militant and effective.

I was impressed, and that’s perhaps why I soon graduated to The Anarchist Cookbook, written by William Powell. First published in 1971, and oozing so much liberty that governments around the world quickly banned it, the handbook included tips for manufacturing everything from telephone phreaking devices to home-made hash brownies.

My taste for black, and for surrealist films, soon followed. Un Chien Andalou was an early favourite: a 1928 short film by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí whose “dream logic” had no plot in any conventional sense.

Then came some serious reading: George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and Noam Chomsky’s American Power and the New Mandarins:

Quite generally, what grounds are there for supposing that those whose claim to power is based on knowledge and technique will be more benign in their exercise of power than those whose claim is based on wealth or aristocratic origin?

I paid attention to studies of the first self-organising affluent societies by the radical anthropologists Marshall Sahlins and Pierre Clastres. Later, I sat at the feet of the priestly Ivan Illich; listened to flamboyant lectures by Herbert Marcuse on feminism and repressive tolerance; and attended seminars on anarchism and ecology by Murray Bookchin.

I met the author of The Female Eunuch and several times, in clubs so small they felt like Turkish baths, heard The Clash rail against petty injustice, plutocrats, poverty and racism.

I found myself influenced by Michel Foucault’s writings on power/knowledge and Guy Debord’s theory of mediated resistance; and I listened intently to lectures by Cornelius Castoriadis in defence of the idea of the autonomous individual lucid in her desires, clear-headed about reality, and capable of responsibly holding herself accountable for what she does in the world.

On Liberty

It was my doctoral supervisor, C.B. Macpherson, who taught me to combine the subject of liberty with the principle of equality, and to do so by way of serious reflection on the past, present and future of democracy. Thanks to the quiet doyen of democratic theory, I became a part-time anarchist.

I still today sympathise with the anarchist disgust for heteronomy and its passion for liberty, with what Saul Newman, in the third of these articles, calls freedom as ownness, or “the experience of self-affirmation and empowerment which ontologically precedes all acts of liberation”.

The formula probably underestimates what Freud taught us: that all individuals are shaped involuntarily by yearnings, unintelligible fragments, fabrications and omissions rooted in childhood.

Yet the great strength of the anarchist emphasis on “self-affirmation and empowerment” is the agenda it continues to set: to recognise the strangeness of our involuntary love of power, to strive to overcome our voluntary servitude, to rid ourselves of the urge “to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us” (Foucault).

The stress placed by anarchism on these themes, and on the principle that arbitrary power relations are contingent, and hence alterable, still rings true. In recent times, the anarchist sensibility has again come alive in many different global settings, from Greenpeace “mind bombs”, the M-15 movement in Spain, Taiwans’s Sunflower uprising to the punk band G.L.O.S.S. (“Girls Living Outside Society’s Shit”).

For the cause of liberty, all this is well and good. Except that anarchism has no special monopoly on these concerns. In practice, conceptually and politically speaking, democracy handles things better, or so I came to think.

Institutions

The following essays by Alex Prichard and Ruth Kinna and Saul Newman emphasise that the anarchist ideal of freedom rejects states, private property in market form, and the “hollow game” of democracy. Such institutions are deemed antithetical to freedom as non-domination.

Written constitutions, watchdog bodies, periodic elections, parliamentary representation, trial by jury, public service broadcasting, education, health and welfare protections: while all these (and other) institutions are motivated by the principle of equality, the anarchists in this series are inclined to dismiss them as mere instruments of disempowerment, as violators of the lives of individuals blessed ontologically with their own “ownness” (Max Stirner’s Eigenheit).

In his contribution to this dossier, Simon Tormey notes how this conviction unwittingly aligns anarchists with the “freedom of choice” and “possessive individualism” (Macpherson) ideology of contemporary neo-liberalism; he rightly emphasises the political foolishness of jettisoning institutions that can function as levers of resistance to injustice and subordination.

My encounters with anarchists taught me something else: in group settings, anarchists demand informality (“structurelessness” as Jo Freeman called it), yet the lack of institutional rules makes everyone vulnerable to manipulation and takeovers by cunning, well-organised factions.

Strategic objections to anarchist ideas of freedom as “non-domination” are compelling; but, arguably, they don’t burrow deeply enough into why anarchism has no love of institutions. Philosophically speaking, anarchism was born of a 19th-century age blind to the embodied linguistic horizons within which individuation takes place from the moment we are born.

Karl Marx had no developed theory of language, yet he spotted (in Grundrisse) that individuals “come into connection with one another only in determined ways”.

Rephrased, we could say, within any culture, that individuals resemble spiders entangled in laced webs of language that structure their time-space identities. What we think, who we are, how we represent ourselves to others and act on the world: all of this, and more, is framed by the linguistic horizons (Wittgenstein called them the language “scaffolding” (Gerüst) of our everyday lives.

It follows that notions of liberty vary according to the language games people play with others. Since individuals are chronically bound through language to the lives of others, the whole image of “free” individuals as “un-dominated by any other” is both a misleading fiction and impossible utopia. How “individuals” define and practise their “liberty” is shaped by their linguistic engagement with others.

And as these entanglements are infused with power relations, individuation is very much a political matter, a process defined by structured tensions and struggles over who gets what, when and how, and whether they should do so.

Complex liberty

The point is that institutions matter. Anarchists excel at criticising factual power, but their proposed counterfactual alternatives are typically weak. The “cult of the natural, the spontaneous, the individual” (George Woodcock) runs deep in their thinking.

Yes, in certain circumstances the “passion for destruction” (Bakunin) can be creative. But loose talk of “unions of egoists” (Stirner), “social communion” (Proudhon) and “camp rules” and “constitutionalism” (Ruth Kinna and Alex Prichard’s iteration) falls wide of the mark.

Loose talk of liberty neglects the fundamental point that the empowerment of individuals, their exercise of freedom understood as “non-domination”, requires their protection from bossing and bullying by others. That is the meaning of the old maxim that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance.

More than a few ugly crimes have been committed in its name, which is why beautiful liberty requires restraint in order to be exercised well. Liberty is no simple thing. It is a political matter bound up with institutionalised struggles for equality among individuals, groups, networks and organisations.

The type of institutions matters. That’s the whole point of democracy: its power-monitoring, power-sharing institutions are designed to conjoin liberty with equality, in complex ways, in defence of citizens and their chosen representatives, in opposition to the disabling effects of arbitrary power.

Armed with the grammar of complex liberty tempered by complex equality, democrats warn of the dark side of anarchism, the dogmatic ism-conviction that in matters of liberty, language and institutions are trumped by the preference for simplicity over complexity.

There’s another sense in which the old anarchist ideology of the autonomous individual is today questionable: its neglect of the non-human. We’ve entered an age of eco-destruction and eco-renewal marked by rising public awareness that we human beings ineluctably live as animals in complex biomes not of our choosing. The contributions below are silent about this trend.

Why? The part-time anarchist in me suspects that it’s because their particular anarchist vision of freedom as “ownness” and non-domination is anthropocentric. Their liberty is the all-too-human licence freely to dominate nature.

If that’s so, then the old subject of anarchy and liberty is confronted by new democratic questions: is it possible to include the non-human in definitions of freedom as the unchecked propensity of humans to act on their worlds?

How might the “ownness” enjoyed by free individuals be brought back to Earth? Can these free individuals hereon be regarded as humble “actants” (Bruno Latour)? Are people capable of living their lives in dignity, unhindered by arbitrary power, as equals, entangled in complex biomes they know are so much part of themselves that they must be their vigilant stewards?

You can read other articles in the series here.