The Conversation is running a series, Class in Australia, to identify, illuminate and debate its many manifestations. Here, Francis Markham and Martin Young explain why the deregulation of gambling in Australia is a long-standing example of class warfare from above.

The growth of “Big Gambling” in Australia is an ongoing class project. It is one that has transferred, with industrial efficiency, billions of dollars from the pay packets of the working classes to the bank accounts of a super-rich elite.

In 1970s Australia, gambling opportunities were limited. The most popular form of gambling was horse race betting. Aside from on-course bookmakers, governments, via TABs, controlled this activity.

Lotteries were similarly government-owned in all states bar Victoria. Sports betting was illegal.

Pokies were clunky, mechanical, single-line affairs. The machines accepted only smaller-denomination coins and were restricted to clubs in NSW and the ACT. Pokies were prohibited even in the four British-styled casinos in the Northern Territory and Tasmania.

Fast forward to 2014 and Big Gambling is ascendant. Pokies have become ubiquitous in pubs and clubs across Australia (except in Western Australia).

Compared to their mechanical predecessors, electronic poker machines are more profitable for the gambling industry and more dangerous to gamblers. Australian company Aristocrat Leisure pioneered the development of linked jackpots and multiline games. These machines encourage gamblers to stake higher amounts and give the misleading impression of frequent wins and near-misses, encouraging gamblers to continue playing for longer periods.

Casinos have been legalised in every state and territory. Despite their rhetoric about targeting “high-rollers”, Australian casinos continue to earn most of their income from the local “grind” market. Casino development is accelerating. Four new casinos are planned for NSW and Queensland in the coming years.

Lotteries have been privatised in every state and territory. Betting, once confined to the trackside and government-owned TABs, has been privatised and deregulated. Odds are available on more sports than ever before and “exotic” bets have transformed even the most banal moment in a sporting match into a money-making bonanza for corporate bookmakers.

The legalisation of internet wagering has made gambling accessible 24 hours a day, wherever a smartphone can be connected. And the final frontier of gambling liberalisation, online casino-style gambling, was recommended for staged liberalisation by the Productivity Commission in its 2010 review.

With such unprecedented opportunities to gamble, Australia has been dubbed the gambling capital of the world. Australians lose more money gambling per person than any other nation. According to the latest official statistics, Australians lost over A$20 billion gambling in 2011-12, a figure that excludes losses on overseas websites. And gambling is rapidly becoming part of how we define ourselves as consumers.

But for an estimated 80,000 to 160,000 Australians, gambling leads to financial, family and psychological problems, and sometimes crime and suicide. As a group, these so-called “problem gamblers” lose a disproportionate amount of money gambling. They contribute a staggering 40% of the total money lost on poker machines.

Given this, it is difficult to imagine a viable gambling industry without “problem gamblers”.

It is similarly difficult to imagine a viable gambling industry without rampant exploitation of the Australian working classes. Both gambling venues and gambling problems are concentrated among the poorest social groups in Australia.

In the western Sydney local government area of Fairfield, for example, which is among the poorest 12% of local government areas in Australia, each adult resident lost an average of A$2340 on the pokies in 2010-11. Across the harbour in Ku-ring-gai and Willoughby, whose residents are among the richest 6% in Australia, poker machine losses were just $270 per adult.

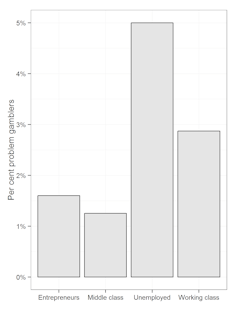

Our own research in the Northern Territory confirmed these class associations. As the figure on the right shows, 2.9% of working-class respondents and 5.0% of unemployed respondents were classified as problem gamblers, compared to just 1.3% of middle-class and 1.6% of self-employed people.

The money lost on gambling by Australia’s working classes flows directly to state and territory treasuries and the gambling industry’s pockets. While around a quarter of gambling losses, ($5.5 billion in 2011-12), ends up in state coffers, the remaining $15 billion a year ends up in the hands of “not-for-profit” clubs and private sector companies.

Only a small fraction of club sector poker machine profits, often justified on the basis of community benefit, are returned by clubs to the community. For example, in 2010-11, clubs in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and the ACT spent respectively 1.3%, 2.4%, 2.3% and 6.6% of poker machine losses on community benefits.

The remaining pokie profits are, according to data from Clubs NSW, mostly spent subsidising “other” activities such as “donations, cash grants, abnormal and extraordinary and other expenses”. In the ACT, for example, gamblers lost over $16 million in 2012-13 playing the 271 pokies at the Canberra Labor Group’s network of clubs. Of these takings, $4.2 million was promptly transferred to the ACT Labor Party.

Commercial gambling has also minted a new class of super-rich individuals. Australia’s second-richest person, James Packer, has poured his considerable inheritance into casinos and profited massively. His majority-owned Crown Limited made a $490 million profit last year, bringing his personal wealth to $7.7 billion.

While Packer’s wealth was partly inherited, Len Ainsworth made his entire fortune from pioneering the “Australian” multiline poker machines. Casino owners around the world favour these machines because of their ability to maximise profits.

After founding both Aristocrat Leisure and Ainsworth Game Technology (AGT), the Ainsworth family wealth is estimated to exceed $1.5 billion. Aristocrat and AGT combined sold over $300 million worth of new pokies in Australia alone in 2012-13.

Hotel owners have likewise shared the spoils, especially Woolworths and its joint-venture partners. Bruce Mathieson, partner in Australian Leisure and Hospitality Group, has amassed $1.2 billion, while Arthur Laundy, Woolworths’ partner in the Laundy Hotel Group, owns pub assets worth $310 million.

Other businessmen to profit from gambling liberalisation include Cyril Maloney ($360 million, pub magnate), John Singleton ($355 million, also pubs), the Kafataris family ($110 million, Centrebet founders) and Matthew Tripp ($115 million, former Sportsbet owner).

Underpinning the gambling industry’s massive transfer of wealth from poor to rich lies a sophisticated (and sometimes not so sophisticated) propaganda that positions gambling as a form of desirable entertainment on the one hand, and a supposed source of economic prosperity on the other.

The current arguments about GDP and employment growth, better entertainment facilities and increased revenue for public spending are largely unchanged since the Victorian government introduced pokies in 1992 (see video below).

The claim that Big Gambling is a source of economic prosperity is dubious. Gambling industries do not create “new jobs”. They simply divert employment from other sectors that are actually more labour-intensive.

Gambling does not create new wealth. It merely transfers wealth from poor to rich and may in fact reduce economic activity due to diverting gamblers from productive labour.

The argument that the transformation of pubs and clubs into a network of nationally linked mini-casinos has provided more entertainment is equally suspect. Public attitude surveys have consistently suggested that pokies destroy entertainment possibilities. As far back as 1999, 54.6% of the adult population disagreed with the statement that:

Gambling has provided more opportunities for recreational enjoyment.

Pokies, especially in pubs, have been associated with the decline of the live music industry. And the new casinos, such as at Barangaroo in Sydney, simply don’t fund entertainment for the general public. According to Crown, the casino is required to cross-subsidise the new “six star” hotel, the hospitality of which will inevitably be limited to a rich elite.

In terms of public revenues, gambling does swell the state’s purse. But this revenue is highly regressive in that it is generated through the exploitation of working-class suburbs (see the map above) and relies heavily on gambling addicts’ losses.

This level of class-based exploitation is only possible because the gambling super-rich are willing to use their money and influence to reinforce their class position. Political power is used to block reform. For example, there was a concerted and ultimately successful effort to sabotage the Wilkie pokie reforms, despite their overwhelming public popularity.

At the same time, donations to the major political parties (mainly the Liberal and National parties) from Clubs NSW and the Australian Hotels Association peaked at a total of $1.3 million in the final quarter of 2010.

Political power is also used proactively to further deregulaton. Clubs in NSW gained further tax concessions and the entitlement to offer new “electronic table games”. More outrageously, the so-called “unsolicited proposal” for the new Sydney casino by James Packer avoided a competitive tender process and selected its own tax rate.

This is after Packer’s late father, Kerry, lost a competitive tender process for the first Sydney casino in the 1990s, despite allegedly threatening a former NSW government with political death should the bid be unsuccessful.

The liberalisation of gambling, especially pokies, has enabled the dramatic redistribution of resources from Australia’s working classes to the country’s wealthy elite. Members of this group use their enormous power and influence to directly sway politicians and policymakers.

These changes have not occurred because of liberated consumers who have chosen, and demanded, that 200,000 poker machines be installed across the country. It has been an exercise in class warfare from above, based on the calculated, industrial-scale exploitation of Australia’s working classes by a super-rich elite.

See the other articles in the series Class in Australia here.