Leading thinkers in environmental economics and conservation are asking a pressing question. Why are we ignoring the destruction of the living world?

Recently, the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) published a global assessment of biodiversity that set out alarming statistics: a million species at threat of extinction, 75% of terrestrial environments severely altered by human activity, and a 30% reduction in global habitat integrity.

Despite all this, practical solutions to redress an ecological crisis — land use and economic reform, action on climate change and improvements to environmental governance — are not prioritised. One key reason for this is how we frame our relationship to the living world.

Instrumental nature

Our prevailing relationship with nature is instrumental – that is, we predominantly frame the living world as a set of natural resources, apart from humans, for our privileged use.

Such framing is so deeply embedded, and our material dependence on nature so total, that it can seem strange even to question the idea of nature as natural resource. In Western nations, this position has deep philosophical and religious roots.

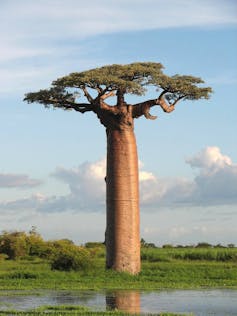

My latest book, The Imagination of Plants, highlights the role of the creation story in Genesis and the philosophy of Aristotle in rendering plants, the living beings that make up the visible bulk of most terrestrial ecosystems, as existing for the sake of animals, and both for the sake of humans.

Read more: Do passages in the Bible justify cutting down forests?

Such accounts have powerfully shaped a human-centred, utility-based worldview that has silenced the needs of plants and animals. They form the philosophical basis of our claims to “own” other species.

If plants and animals exist for the sake of humans, why take action to conserve them when they’re not useful? Why care when their numbers are going down, as long as we can still get what we materially need from them?

Conservation concepts and strategies that place the living world within this frame, including ideas of natural capital, ecosystem services and the protection of the living world for our enlightened self-interest, are destined to fail because they do not address this underlying framing. Indeed, as researchers have pointed out, by not addressing such framing they perpetuate the very drivers of biodiversity loss.

Read more: Money can't buy me love, but you can put a price on a tree

Intrinsic value

Environmental thinkers have warned for decades that such a view of nature is at the root of our ecological crisis. More recent research has argued against this instrumental view, criticising its value as a basis for conservation action.

Since the 1980s, discussions of the intrinsic value of nature – “valuing it for what it is, not only what it does” - have happened across a number of environmental disciplines. This led to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), founded on the cornerstone of the intrinsic value of biological diversity.

In some countries, such as New Zealand, the concept of intrinsic value appears in major pieces of resource management and conservation legislation. It has been instrumental in recent legal battles over land use.

Recent work by environmental philosopher Michael Paul Nelson shows people acknowledge the intrinsic value of nature. He argues that the only reason we make decisions inconsistent with this value is because we don’t believe the general populace shares this belief.

But the concept of intrinsic value does not demand a move away from a dominant use-based frame. In the preamble of the CBD itself, intrinsic values sit alongside a raft of use-based values, including economic, scientific, educational, cultural and aesthetic values. The power of the use-based frame dominates the concept of intrinsic value.

All our relations

There is an alternative to the dichotomy of a purely instrumental relationship and the concept of intrinsic value.

In many Indigenous cultures, such relationships are built on fundamental kinship with the living world, a kinship that actually blurs and subverts the very concepts of nature and culture.

Within these kinship relationships, the needs and capacities of living beings are acknowledged, not left in the background. This is what the late anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose called the Indigenous ethic of connection, or what is also called kincentric ecology.

Kinship offers a way of connecting to nature that acknowledges our need to use plants and animals, but constructs relationships beyond use. Where the concept of intrinsic value can be difficult to engage with, kinship relationships naturally extend to care, respect and responsibility.

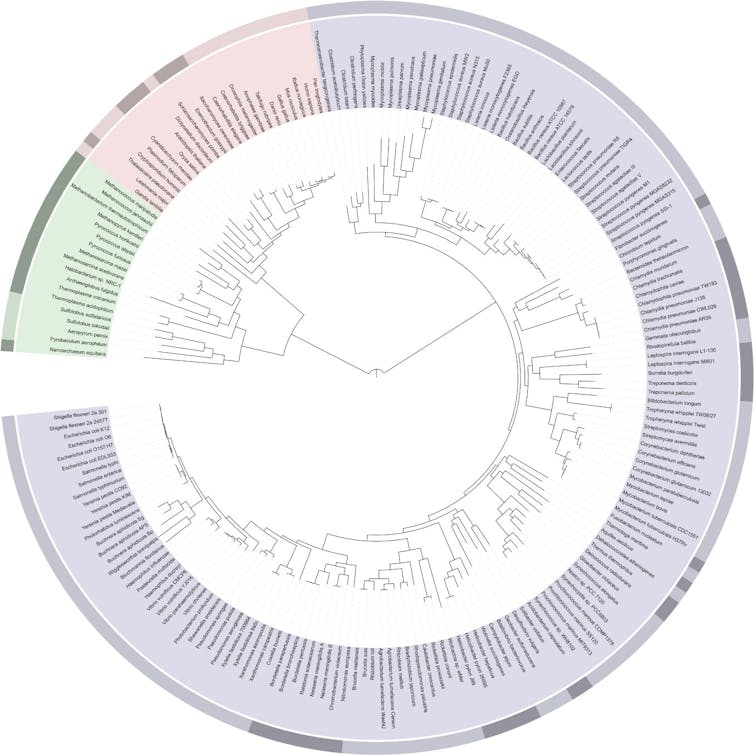

Framing nature in terms of kinship can motivate people to care and make the loss of the living world real for people. Ever since Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, science has known of our fundamental kinship with nature. Yet we don’t frame (or live with) nature in a way that honours this.

A recent example gives me hope. At the school climate strike, a young Brazilian Indigenous woman addressed a crowd in New York, speaking in terms of kinship about the human children of a mother Earth, fighting to save their mother from destruction. Framing nature in terms of kinship noticeably energised the crowd of young people.

The challenge to reframe the living world in terms of kinship is massive. A good step would be to convene a human-nature kinship platform as a way of influencing the UN Biodiversity Conference in China next year. Another step could be to enshrine our fundamental kinship with other species in all major environmental governance frameworks, including the CBD and national environmental legislation.

Both could provide the springboard for us to undergo the hard work of talking about, and living with, other species in ways that acknowledge them as our earthly relations.